Next Generation: Grappling with loss of life and connection, Native youth transform into the leaders of tomorrow

Amid loss of life and physical connection, Native youth are transforming into the leaders of tomorrow.

Amid loss of life and physical connection, Native youth are transforming into the leaders of tomorrow.

Editor’s Note: Coronavirus has devastated Native American communities and put a spotlight on some long-standing problems in Indian Country that have made this pandemic that much worse. But at the grassroots level, everyday heroes have stepped up to help. Part of a series.

PHOENIX – In March, Tawny Jodie was preparing to travel to Israel for her first trip overseas. By July, she was masked and delivering food boxes in rural New Mexico amid a deadly pandemic.

As a full-blooded Navajo, the 20-year-old said she was compelled into service when COVID-19 started ravaging her community and others across the Navajo Nation.

With the virus disproportionately affecting tribal nations due to health disparities, poor infrastructure and chronic underfunding to fix persistent problems, young people like Jodie have stepped up to help others, preserve their culture and start the healing process.

Jodie is one of several young adults living near Window Rock who shared what their lives have been like these past few months – and what’s kept them going as they look ahead to a future beyond coronavirus.

Before the pandemic, Jodie was attending the University of New Mexico in Gallup and working part time at Domino’s Pizza while living with her parents, a younger brother and an older brother and his family. After COVID hit, another brother moved back in with his girlfriend and their son.

The Jodie family’s home in Fort Defiance, Arizona. (Photo courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

While she adjusted to living at home with nine other people, coronavirus cases across the reservation began to climb.

In April, with over 350 positive cases, the Navajo Nation began enforcing 57-hour weekend lockdowns that prohibited people from leaving their homes for nonessential reasons.

“That really swept me off my feet, and I had no idea that all of these regulations would come,” Jodie said. “So I was just full of anger, resentment, bitterness, and I was just tired, like exhausted.”

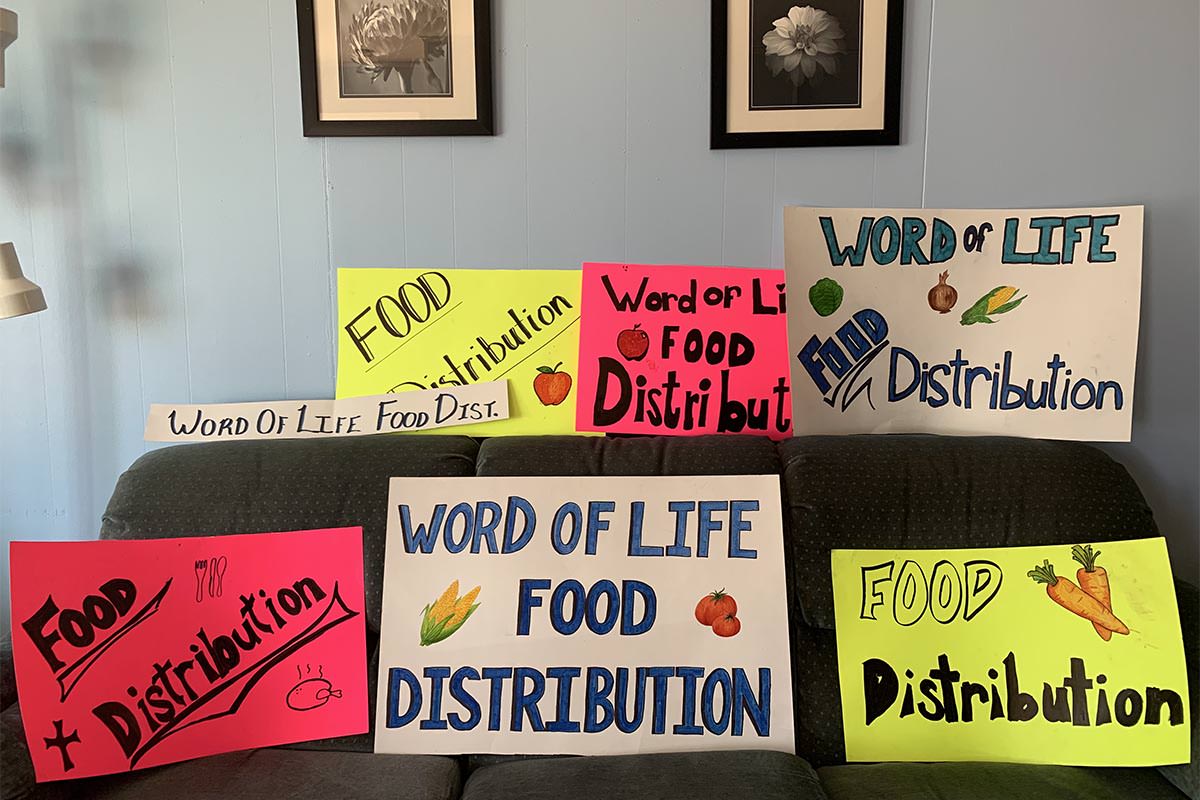

It was especially tough when her study tour to Israel was cancelled, but Jodie said she found a sense of peace by turning to God and service. She traveled with 26 high school and college students as part of a weeklong mission trip to Mariano Lake, New Mexico, to distribute food boxes to families and the elderly.

Tawny Jodie says serving her community with other young adults who share her Christian faith gave her the encouragement she needed to keep her spirits up when she returned home. (Photo courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

Jodie documented some of her daily moments while on her service trip. (Photos courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

Jodie documented some of her daily moments while on her service trip. (Photos courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

“Every day we’d deliver 10 to 12 boxes of food to families in the neighborhoods. … I don’t think anyone just asked them how they were doing during this time. So it was like a sweet meeting, just being able to get to know people and how they’ve been.”

After returning from that work, Jodie gave her youngest brother, Tawry, a hand tending to his 20 chickens and growing watermelon, corn, strawberries and tomatoes in his newly constructed greenhouse. It helped them grow closer.

Jodie’s brother, Tawry, spends much of his time in his chicken coop and greenhouse. (Photos courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

Jodie’s brother, Tawry, spends much of his time in his chicken coop and greenhouse. (Photos courtesy of Tawny Jodie)

Jodie’s passion for helping others and cultivating relationships is perhaps best seen in her work as a youth leader at a local ministry called HighLife Window Rock.

Seth and Sarah Stevens started HighLife for Navajo youth. (Photo courtesy of Seth and Sarah Stevens)

Seth and Sarah Stevens celebrated their first wedding anniversary on March 16, only days after Navajo President Jonathan Nez declared a state of emergency because of COVID-19.

Seth, 28, and Sarah, 26, started HighLife soon after they got married – to create a safe space for teens to grow in their faith and develop healthy coping mechanisms for dealing with trauma, addiction or other struggles.

Although the ministry is rooted in Christian principles, the couple said their priority is to support Navajo youth of any background, help them find their passions and guide them to become leaders in their communities.

“During this time of COVID, the next generations underneath are starting to feel like, ‘Oh, we don’t have our elders anymore. Now it’s our turn. It’s up to us to preserve our history, our culture, our faith, our beliefs,’” Sarah said.

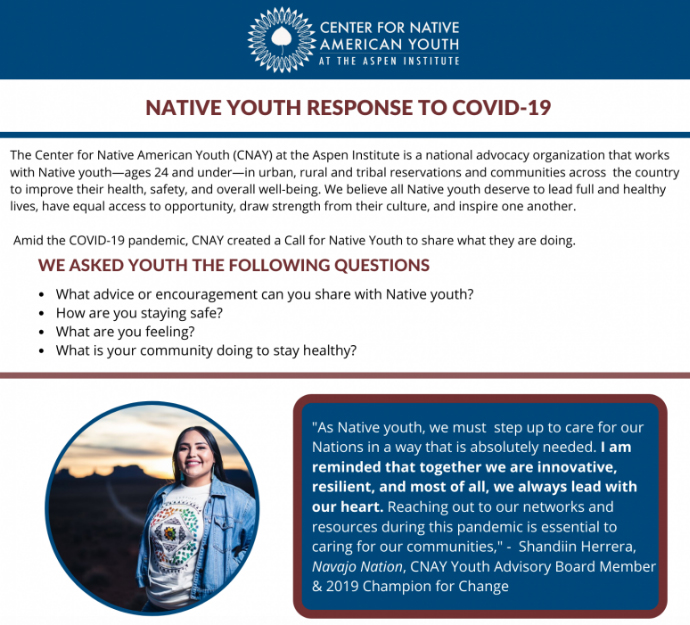

Outside the Navajo Nation, organizations like the Aspen Institute’s Center for Native American Youth are looking for ways to create virtual communities to ensure young people don’t feel deserted as the pandemic and social distancing persist.

Nikki Pitre, executive director of the Center for Native American Youth, laughs as she poses with the 2020 Champions for Change at the Capitol in Washington, D.C. (Photo courtesy of CNAY)

Nikki Pitre, a member of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the center’s executive director, said the center and its youth advisory board created a weekly webinar series to foster a space for Indigenous young people to discuss topics that are important to them through the lens of the pandemic, including decolonizing democracy, LGBTQ+ rights and mental and physical well-being.

The Native Youth Response to COVID-19 is just one effort to reach Native youth during the pandemic. (Courtesy of CNAY)[/caption]

“It is our responsibility to build up Native youth, whether it’s teaching them about how to use your voice, how to use social media, how to get involved in civic engagement, how to make sure that young people know that who they are and what they say matters,” Pitre said.

It’s usually quiet outside 14-year-old Nehamiah Hardy’s house in Window Rock, unless he and his three younger brothers are out riding their bikes. With extra time on his hands this summer, Hardy has been volunteering at HighLife as a sound engineer, photographer and videographer for the digital videos they began making after the ministry moved online.

“It’s just been good to keep your mind off other things,” he said. “It’s kind of become a new hobby.”

Photographing landscapes and discovering new trails at nearby Window Rock park and memorial have helped him cope with the social isolation and devastation of the pandemic. In mid-July, he and his family took a road trip to Carlsbad, California, and although Hardy said he was hesitant at first, the change of scenery was a much-needed breath of fresh air.

Hardy’s photos from his summer adventures in Carlsbad, California, and Window Rock. (Photos courtesy of Nehamiah Hardy)

“The sunsets were really nice and the waves, the sound of them. I know it probably sounds really overrated, but it’s really nice.”

Prior to the trip, Hardy’s uncle contracted COVID-19 and was in the hospital on a ventilator for two weeks. He’s home now and recovering, but Hardy recalls that time as “pretty shocking” and said he felt “speechless.” He’s tried to focus on being a role model for his younger brothers and encouraging them to wash their hands and help out around the house.

On the left, Mikah Carlos, chair of the CNAY Youth Advisory Board, poses with Paulette Jordan, a U.S. Senate candidate in Idaho, after the 2020 Champions for Change event in Washington, D.C. (Photo courtesy of CNAY)

Mikah Carlos, a member of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, jokes that she’s an “elder youth.”

She’s just 25, but as chair of the youth advisory board at the Center for Native American Youth, she now mentors other young people. The experience has helped her grow, enabling her to advocate for other youth if they aren’t yet comfortable speaking up for themselves.

“I always want to really encourage them to speak up and share (their experiences) … but sometimes they’re not ready to share their stories. And so until they’re ready to do that, I don’t mind amplifying their voice,” Carlos said.

One of the biggest ways Native young people and youth advocates are using their voices is by changing the perception about Indigenous communities, especially during this time.

Pitre said they’re already operating at a “deficit narrative,” with much of the focus being on what tribal communities lack, rather than what they’ve created out of limited resources and colonization. She said it’s especially important for young people to acknowledge that yes, there may be “intergenerational trauma,” but, more importantly, there is “intergenerational strength” that they can draw on amid the pandemic.

Much of the news coverage around COVID-19 and the Navajo Nation has focused on its rampant spread due to health problems and poor sanitation. Seth Stevens said while these issues are prevalent, they miss how cultural differences, such as the importance of community and staying physically connected to family, play into the spread.

“It’s not because we’re careless,” he said. “It’s because we care so much for one another that we cannot stay away from our elders.”

In May, after finishing up her third year at Indian Bible College in Flagstaff, Brina Lee moved in with her mom in the reservation community of St. Michaels. Like so many college students, the 23 year old had to adjust her routine and grow accustomed to being back home under her mother’s watch.

She said their relationship has been difficult over the last several years, so it’s been challenging to live under the same roof. At the same time, she said, there have been “a lot of blessings” in rebuilding their connection and growing together in their Christian faith by “allowing the words (of the Bible) to penetrate through (her) heart.”

Although she is not close with her grandparents, Lee said seeing so many older people die across the Navajo Nation has been “frustrating” because of the wisdom that is lost with their passing.

“They had to endure through so much, and yet they’re taken out by sickness, by some virus. That’s something I’m struggling with: How do I not act out in frustration toward the virus? But how can I live through it?” she said.

Walking, praying and journaling have been a respite for Lee. She’s also discovered a sense of purpose over the last few months, whether that be by doing yard work to prepare for winter or by walking to a wooded area about 20 minutes from her home.

“I’m able to take my focus off of me and redirect it back to others … not being trapped in a four-(walled) room feeling helpless or lonely, but going out and seeing creation and feeling that fresh breeze or smelling the red dirt, like it really just makes your feet feel planted,” Lee said.

Even as the pandemic goes on, this process of healing has begun for so many – but it’s far from complete. Youth leaders are encouraging their peers to find ways to process trauma and mourn the loss of loved ones to the virus.

“When COVID is over, our young people are going to need something to turn to. They’re going to be thirsty for something to turn to,” Pitre said.

“We don’t want them to turn to drugs, to alcohol, to anything unsafe. So what is our responsibility to make sure that young people turn to their culture, turn to traditional ways of knowing … tend to their families?”

Added Seth Stevens: “We don’t believe in coincidence. We have to believe, and even as Navajo believe, that this is for a purpose and reason, and we can easily miss it if we don’t really look into it. If we just focus on our pains, we can easily miss the purpose behind it.”

As of Sept. 6, the Navajo Nation had more than 500 COVID-related deaths, but there are signs that the spread is slowing down, with fewer than 100 new cases daily since June 26. Despite these signs of improvement, President Nez recently told tribal members that recovery will happen “slowly, gradually” until there is a vaccine.

“Here on the Navajo Nation, we continue to flatten the curve, but we cannot become complacent or careless in our daily activities, especially when we are out in public,” Nez said in a statement.

For now, Jodie, Hardy and Lee will continue living at home, following government guidelines and doing their best to stay away from others, but they’ve started to think beyond the hurt and loss to what they’re looking forward to most – normalcy.

“I miss going to the beach,” Lee said. “The beach was one of my favorite places to be. But I’ve also been thinking about going up to Oregon just for fun.”

“Photoshoots with friends, definitely,” Hardy said. “I can’t wait to get some really cool shots.”

“The one thing I’m super excited about is just going to see some of my closest friends,” Jodie said. “Also just … I’m really looking forward to not being afraid of people.”