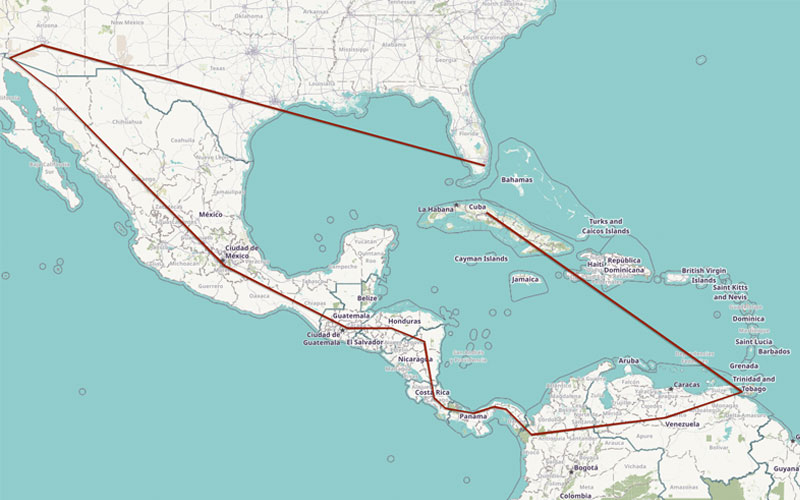

This is the route Maureny Reves Benitez and her parents took from Cuba to the United States after the Obama administration ended the “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy in January 2017. (Map by Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – It took Maureny Reves Benitez almost two years and thousands of miles of travel by boat, bus and foot through nine countries and the most dangerous jungle in the world to reach Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport.

She arrived near midnight on Nov. 15, 2019. As she waited in a corner of the airport for the next leg of her trip, she spoke to Cronkite Borderlands Project about her improbable journey.

It started in her native Cuba, Maureny said, where she was branded the “daughter of a traitor,” quashing hopes of a promising future.

The journey included harrowing experiences: She fled the communist-controlled island in a rickety boat in turbulent seas and sang to calm her fears of drowning. Soldiers – seeking to rob her of hidden money – strip searched her in Venezuela. She spent her 17th birthday crying and afraid, struggling to cross the perilous Darién Gap that straddles Colombia and Panama. And she and her parents spent months in a shelter in Mexico waiting for U.S. immigration officials to allow them entry.

“I just can’t believe that I’m finally here,” Maureny said.

Maureny, her father, Yanko Reves Ricardo, and her mother, Anisleydis Benitez, were in the United States at last. But for how long remains uncertain.

They are political asylum-seekers whose journey to the United States was heavily influenced by fast-changing immigration policies under the administrations of Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

A key change impacting Cuban refugees came in the final days of Obama’s presidency, when authorities ended a two-decade old policy known as “wet-foot, dry-foot,” which allowed Cubans who made it to U.S. soil to stay in the country and automatically become legal permanent residents.

Maureny Reves Benitez lived at Casa del Migrante in San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, for a few months before legally entering the U.S. (Photo by Lidia Terrazas/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

For many Cubans, the policy had been worth risking the dangerous 100-mile boat trip to Florida. Its termination meant that many Cuban refugees, including Maureny and her family, would have to apply for political asylum like applicants from other countries. It also changed migration patterns, with Cuban refugees now willing to take long, complex routes to get to the southern U.S. border, where they could try to enter the country illegally or apply for asylum.

Those who do reach the southern border are delayed by a policy known as metering, which requires them to remain in Mexico until notified to start the application process. The wait can last months.

The policy was used on a limited basis by the Obama administration in 2016 to “meter” a surge of Haitian migrants seeking asylum, but it has been greatly expanded under Trump.

The wait for Maureny’s family was a long one – five months in Mexico. But they were among the fortunate, able to stay in a shelter in San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, before getting the call from U.S. immigration officials that ultimately landed them at the Phoenix airport that November night.

From Phoenix, the next destination was Miami, where friends of the family had helped arrange housing in nearby Naples, Florida. In Florida, Maureny returned to school.

“My dad always told me – you have to go to school to become someone in life. But this isn’t just for him, it’s for me,” she said.

On May 13, almost seven months after arriving at Sky Harbor, Maureny graduated from high school in Florida.

Whether the U.S. becomes Maureny’s permanent home depends on whether authorities approve the family’s asylum applications. The answer likely won’t come soon. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service says the process takes an average of six months, but some cases last years. According to the Department of Justice, nearly 213,000 applications for asylum were filed in 2019 and about 19,000 were granted. As of March, the U.S. immigration courts had a backlog of over 1 million pending immigration cases, including asylum cases.

Family flees to Trinidad and Tobago

The family’s odyssey began when Maureny’s father, Yanko Reves, an English professor in Cuba, was branded a critic of the island’s government and eventually forced to flee to Trinidad and Tobago – a nation comprising two islands near Venezuela.

“He was persecuted for thinking differently,” said Anisleydis Benitez, Reves’ wife.

In Cuba, Maureny had hoped to study tourism, but she was denied early admission into the program because her father was considered a defector – she was ultimately branded “the daughter of a traitor,” Reves said.

Reves was granted political refugee status by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees in 2015, and he left Cuba for Trinidad and Tobago. It wasn’t until two years later that Maureny and her mother were granted the same protection and allowed to join him.

There, they became part of a small community of Cuban compatriots. In 2017, according to UNHCR, 36% of officially designated refugees – 117 people – in Trinidad and Tobago were Cuban nationals.

But life for refugees in Trinidad and Tobago, as in most Commonwealth Caribbean countries, was difficult. The nation passed a refugee policy in 2014 promising work authorization, identity documents, travel documents, public assistance, medical care and more, but Reves said implementation is almost nonexistent.

As a result, the family requested that UNHCR transfer their refugee status to another country. When that was denied, they decided to leave their political security in Trinidad to head to the United States.

“You can see it in our paperwork,” Reves said, “we did not ask to be transferred to Canada or the United States. All we asked was to go to a country where we can work, a place where we can contribute to society.”

Maureny remembers talking to her father before they left Trinidad. He asked how she felt about the journey ahead. “I told him that if others do it, I can, too,” she said.

They joined 27 other immigrants in a shabby boat in the middle of the night. It took six hours to reach Venezuela.

She recalled that the ocean current was so strong and the boat so unsteady, she began to cry like a baby. For strength, she envisioned her grandmother, who stayed behind in Cuba. She began to sing a church hymn that her grandmother sang to her when she was a little girl. Just like that, she said, the current weakened and she felt safe again.

“When I started singing, everyone on the boat started singing along – some of them didn’t know the words, but they sang anyway,” she said.

Reaching Venezuela, Maureny said, was “a miracle.”

The family expected to encounter difficulties in a country in the midst of political upheaval, hyperinflation and violence and corruption. But they were not prepared to be stripped naked by Venezuelan military men at an immigration checkpoint.

“We told them that she (Maureny) was under age and they said that we were in Venezuela, and they could do what they wanted,” Reves said.

Maureny described how her mother went to great lengths to hide their cash, such as sewing it into their bras and even hiding some in their feminine pads. The Venezuelan officials separated Maureny from her parents. She said she was blinded by fear and uncertainty, and sobbed uncontrollably.

“They told me to calm down, and that as long as they got what they wanted from my parents, I would be fine,” she said, sobbing quietly.

“They took everything from us, they even took our food.”

Migrants stand in sandals, flip-flops and bare feet at the bank of the Tuquesa River at the Bajo Chiquito camp in the Darién province of Panama on March 7, 2020. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Family faces dangerous conditions through Colombia and Panama

Still, the family made their way over land to Colombia, where they had to traverse the unforgiving Darién Gap, a 60-mile stretch of dense jungle that straddles the Colombia-Panama border.

“My dad told me to look straight and to keep walking. He said nothing bad would happen to me because he was there to protect me,” said Maureny, who turned 17 in the jungle.

“It was the worst birthday,” she recalled. “I was crying, and I couldn’t go on anymore. (The next day) a soldier saw me and overheard that it was my birthday. Later he gave me a candy bag, and that made my day.”

She reminisced about the last birthday she spent in Cuba. She had turned 15 and as is the custom on the island – her friends and family woke her up exactly at midnight with cake while singing “Cumpleaños Feliz” – “Happy Birthday” in Spanish. She never imagined that two years later, at exactly midnight on her birthday, a group of fellow migrants would serenade her to the same tune while hiking through the jungle.

It was still Maureny’s birthday when the migrants encountered armed men. According to the family, one man ordered everyone to walk in a single file line and throw their backpacks to another man.

“One of them said,‘The only thing we don’t do is rape women because our boss is against that,'” Reves said. “They even took someone’s baby formula. They told us that we were almost there. ‘One more day,’ they said, but they lied.”

Thinking they had only one day left in the jungle, Reves offered to share the family’s rations with those who had been robbed.

The group continued the next two days without food and with very little water, resorting to desperate measures to survive.

“A Haitian woman who was part of the group sprinkled salt into our hands and told us to put it on the tip of our tongue,” Reves said. “That’s how we made it.”

The Darién Gap, considered the most dangerous jungle in the world, once was home to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. According to SENAFRONT, Panama’s national border service, last year alone more than 22,000 migrants crossed the Darién and arrived in Bajo Chiquito, in eastern Panama. Migrants trek through the dense jungle to escape poverty, political unrest, and armed conflict in their native lands. The journey can take days or even weeks for the unfortunate who get lost. An untold number die in the Darién Gap.

After days of walking, Maureny and her parents reached Puerto Obaldía, an indigenous town 42 miles southwest of the border with Colombia. This is where many migrants make initial contact with the border service and where they rest and recoup before continuing through the seemingly endless jungle.

It was in the outskirts of Puerto Obaldía where Reves Benitez and her parents met Second Cpl. Gonzalo Adalberto Castellon, part of the SENAFRONT unit that patrols the Darién Gap looking for drug traffickers (he was the “soldier” who gave Reves Benitez chocolates as a belated birthday gift). Castellon, interviewed in April, recalled his gesture.

“I remember it was May 2nd, if I’m not mistaken,” he said. “I’m a giver, and whatever I have I try to give to others.”

In his eight years with the border patrol, Castellon has seen how surging migration flows have altered his country, especially the remote villages that have become temporary shelters for migrants. Although Panama’s resources are being overextended by the surging flow of migrants, he expressed admiration for the people who commit to the uncertain journey to the United States.

“Walking through the Darién jungle is hard,” he said. “It’s even harder for people that come from other countries and don’t know what’s ahead. We are used to it, and it takes a lot out of us – imagine them.”

Maureny and her family rested less than a day in Puerto Obaldía. They refused to waste precious time and headed to the next encampment, Bajo Chiquito, a tiny village near the Tuquesa River that has turned into the Panamanian welcome point for migrants who’ve completed the trek through the Darién Gap.

A visit to Bajo Chiquito in March painted a picture of what Reves Benitez’s family encountered.

The homes in the village are run down; colorful arrays of tents cover the unpaved ground, and clothing hangs from nearly every precipice. At any given time, hundreds of migrants are in Bajo Chiquito.

Migrant tents and residential dwellings sit next to each other in Bajo Chiquito, a village and migrant camp in Panama’s Darién province, on March 7, 2020. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Some sit next to their children, holding black plastic bags that contain what’s left of their belongings. Others crowd around visitors to complain about the lack of clean water, the illnesses their children contracted, and the horrors they faced crossing the jungle. Some said armed criminals raped both men and women.

Migrants usually spend about a week in Bajo Chiquito before heading to – La Peñita, a camp further downriver. There are two ways for migrants to get to La Peñita. One is to pay $25 a person for a two-hour boat ride, an expensive service provided by locals; the other is to walk along a dusty road for at least six hours, depending on weather conditions.

Maureny and her parents, desperate to escape bouts of diarrhea that killed one migrant in Bajo Chiquito, opted to walk. After walking for hours in adverse weather, Reves said he grew concerned with the blisters his daughter and wife were developing, so they detoured into an indigenous village.

“There I rented a horse for $20 for my little girl and my wife … I walked alongside the horse until we made it to Peñita,” he said.

In La Peñita, migrants are processed by SENAFRONT using a U.S.-designed biometrics registration process known as BITMAP, to track migrants as they make their way through Central America to Mexico and, perhaps, the U.S. border.

The border service deploys units along the Darién Gap to supervise and protect migrants along the difficult and sometimes fatal journey. Their model of operations combines protection protocols with a humanitarian approach, said SENAFRONT’s director general, Oriel Ortega Benitez, Panama’s top border official.

“It’s will. It’s a calling for the service,” he said. “We transform our strength into different types of work according to the needs. I can assure you that even our special forces units who are under extreme pressure in the jungle – when they go to the communities, they get rid of all that power, and they begin to work with people.”

Despite SENAFRONT’s efforts, the situation in La Peñita is dire. The village lacks the most basic necessities, including access to clean water for drinking and bathing.

Alexis Betancourt, commander of SENAFRONT’s eastern brigade, which deals with the Darién region, said the country has struggled to keep up with the increasing numbers of migrants.

“The flow hit us unexpectedly. We contemplated temporary shelters, but those shelters closed when the migration flow was stabilized,” he said. “La Peñita remained, and there we were able to combine resources and amenities – we brought in external organizations,” referring to the Red Cross, Global Medical Brigades, UNHCR and others.

The village is self-divided by nationalities – Haitians all in one place, along with Cubans; five migrants from Yemen who stick together; and so on. Migrants are expected to spend no more than a week in the village before being transported to Chiriqui Province, near the Costa Rica border, the third and final migrant shelter supervised by SENAFRONT. But policy changes in other Latin American countries, security checks of individual migrants and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic have caused delays, extending the stay in La Peñita sometimes for months.

Panama, which sits between North and South America, has become a transit country for thousands of migrants from around the world fleeing violence, poverty and bigotry. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Bordlerlands Project)

Family continues journey through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras

Panama and Costa Rica work in conjunction under a process almost identical to the metering system on the U.S.-Mexico border. Immigration services in Costa Rica allow only 100 people to cross the border each day. This significantly delays the journey of many migrants – Maureny and her parents spent one month in Panama before crossing into Costa Rica.

While in Chiriqui Province, Maureny’s family met Second Cpl. Heidderger Arauz of SENAFRONT. He became more than a border patrol officer to them – the family considers him a friend.

Arauz, who is part of SENAFRONT’s vehicle maintenance unit, said that after seeing Maureny’s mother several times, he asked whether she was Cuban – which he suspected because of her accent. Arauz, who worked in radio several years ago, said he often did comical impressions to brighten the mood around the shelter.

Benitez said Arauz checked in regularly with her family, exchanging anecdotes and jokes. They agreed to stay in touch and continue to do so.

“Our profession allows us to uncover callings within us … finding that people have a necessity and that it’s not easy to leave your country for a better life,” Arauz said. “For me, this is good behavior towards people that are transitioning from country to country.”

After leaving Panama, Maureny said, they moved without major problems through Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

They were nearly penniless when they reached Honduras, which grants humanitarian visas that allow migrants from Cuba and other countries to continue their journeys without risk of deportation.

The family camped outside an immigration office in the pouring rain to plead for humanitarian visa after authorities tried to charge them the equivalent of $180 U.S. dollars for the document – 10 times what they had expected to pay. The family instead boarded a bus without proper documentation – risking deportation – and headed to Guatemala.

They encountered no problems, and after riding through Guatemala in a single day, they reached the migrant settlement of Tapachula in southern Mexico. Thanks to good timing, they secured a humanitarian visa offered by the Mexican government known as the salvoconducto – Spanish for safe conduct – document, which allows migrants to travel to the U.S. border without the risk of deportation.

The Mexican government temporarily halted the salvoconducto policy in mid-2019 under pressure from the Trump administration. Although it still exists, issuance of the visa has slowed to a trickle.

But Maureny and her family were fortunate. With the document, they reached the border town of San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, across the border from San Luis, Arizona, without issues. There, they added their names to the list of almost 1,500 migrants waiting to plead their cases for asylum with U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents.

The Reves family was among nearly 1,500 migrants waiting to plead their cases for asylum with U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. (Photo by Ken Bosma/Flickr)

Finding shelter in Mexico, making it to the U.S.

While they waited in Mexico, Maureny and her family asked for refuge in Casa del Migrante, a well-maintained temporary shelter just a five-minute drive from the border crossing at San Luis Rio Colorado.

Casa del Migrante is a privately owned shelter originally created to help recent deportees from the U.S. With the influx of migrants from Central America, Haiti, Cuba, Africa and elsewhere, the shelter has shifted its focus, said the director, Martin Salgado.

“When this asylum phenomenon started about one year ago,” he said, “we started to work with them. We have 85 beds, but on a hard day, we can have more than 100 people.”

Salgado said CBP officers call the shelter almost every day – either early in the morning or in the afternoon – and ask for a set number of people. Salgado drives migrants to the border crossing, introduces them to CBP agents and stays near until officers allow them into the facility.

The first round of questioning takes place just outside CBP offices – on the pedestrian border crossing, still on Mexican territory.

On Nov. 1, CBP agents called the shelter at 9 a.m. and asked Salgado to drive 10 migrants to the border crossing – including at least one family with children. Maureny sat on a bench near the pantry room, smiling and staring as shelter staff prepared the six adults and four children for the coveted but dreaded drive to the border.

She said she felt anxious but remained hopeful that her number – 929 – would be called some day. If her turn came, Maureny said, she would call her parents at the restaurant where they worked just a few blocks from the shelter to urge them to hurry back to Casa del Migrante.

The family waited almost five months to cross into the United States after arriving in Mexico. For a 17-year-old, it was a long five months.

“I just want to make friends again, I want a small house, and I want to study. You know, I was pretty good in school. Maybe I want to be an architect, or I can be like you – do what you do,” Maureny said in an interview at the shelter on Oct. 12, while fidgeting with an old, cracked cellphone in the dining area of Casa del Migrante.

Maureny Reves Benitez fulfilled her dream of returning to school, and in May, she graduated from high school in Florida. (Photo courtesy of Anisleydis Benitez)

When 929 was called, Maureny and her family were processed by CBP officers at the border and transported to Phoenix, where they were processed a second time by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE customarily turns migrants over to local churches and other temporary shelters that arrange for migrants to travel to their sponsors in the United States to await a status decision. This process originated after ICE was widely criticized for dropping migrants off at Greyhound bus stations with one meal in a Ziploc bag and a bottle of water.

According to a legislative attorney, at this time, 11 border cities use the metering system. According to Salgado, CBP officers usually cap the number of people allowed into the U.S. at no more than 10 per day – and sometimes as few as three.

In the early morning of Nov. 16, Maureny and her family boarded a plane to Miami to complete the next leg of their journey.

With the help of a family friend, Maureny’s parents bought a small mobile home in Naples.

It may take up to three years before Maureny and her family receive a final decision about their asylum case – assuming they pass the “credible fear” screening, which is a standard for granting political asylum. But the uncertainty doesn’t prevent them from feeling at home in Naples.

“I did not think things here were going to go so well for me, but they have,” Maureny said.

After trudging through Latin America for almost two years, she was overjoyed to learn that Citizenship and Immigration Services requires migrants to enroll in high school immediately. That had been her dream for a very long time – to go back to school, to make new friends and to have a home.

And despite school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic – Maureny graduated from high school in May, happy but still reflective about her journey.

“It’s hard to leave your home when you don’t want to. We didn’t want to leave, we had to.”

Cronkite Borderlands Project is a multimedia reporting program in which students cover human rights, immigration and border issues in the U.S. and abroad in both English and Spanish.