Craig Station, a coal-fired power plant in northwestern Colorado owned by Tri-State Generation and Transmission, is slated to shut down by 2030. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

CRAIG, Colorado – Coal-fired power plants are closing, or being given firm deadlines for closure, across the country. In Western states supported by the overallocated and drought-plagued Colorado River, these plants use a significant amount of the region’s scarce water supplies.

With closure dates looming, river communities are starting the contentious debate about how this newly available water should be put to use.

That conversation is just beginning in Craig, in the northwest Colorado, which is home to nearly 9,000 residents and hundreds of coal industry workers. In January, Tri-State Generation and Transmission announced it will fully close Craig Station by 2030. The same goes for the nearby Colowyo coal mine.

The news comes on the heels of several high profile closures or closure announcements in Arizona, Wyoming and New Mexico. Each has a coal plant that taps into the Colorado River or its tributaries.

That didn’t surprise Jennifer Holloway, director of the Craig Chamber of Commerce.

“To me, it was, in a way, a relief because it allowed for the whole community to be aware this is really happening,” Holloway said during an interview.

“It’s been hard to face the fact that, ‘OK, we aren’t needed’ because we’ve been providing electricity for millions of other people. And that is a source of pride.”

At first, people worried about the loss of jobs and the ripple effects it would have on local businesses. Craig’s economy is intimately tied to the power plant. But as the conversation about the announcement continued, Holloway said, other nagging questions came up, such as, what’s going to happen to the plant’s sizable water portfolio? It uses more than 10 times as much water than Craig’s entire population.

In the arid West, water, and access to it, is crucial to local economies. Where water goes – to a power plant, a residential tap or down a river channel – says something about a community’s present and future economy and its values.

“People have different views,” Holloway said. “But my personal view is that that water needs to be safeguarded for long term environmental usage.”

With nearly a decade until the shutdown, other local officials feel the discussion is premature, preferring to confer with Tri-State before commenting on how they’d like to see the water from Craig Station be put to use.

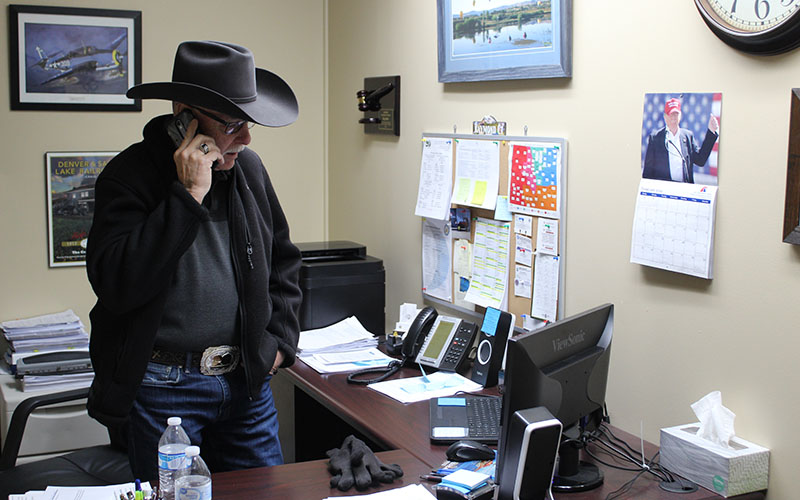

“I personally never thought I would see the day that this would come about,” said Ray Beck, a Moffat County commissioner and a longtime booster of coal.

Ray Beck, a Moffat County commissioner and former mayor of Craig, Colorado, says it’s too early to talk about what will happen to water used by the Craig Station when the plant shuts down in 10 years. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

“Water has become quite a commodity, if you will. And it’s very precious,” said Beck, who would like to see some of it set aside to give a boost to local farmers and ranchers.

His worst-case scenario?

“That it didn’t get utilized for anything, and they (Tri-State) just hung onto the water right,” he said.

Holloway wants to see Craig make a transition that many other Western communities have attempted over the past century, from an economy based on extractive industries to one based on recreation. She’s quick to name drop the region’s new slogan – “Colorado’s Great Northwest” – and list the various draws, such as Dinosaur National Monument, the nearby Steamboat ski resort and the relatively free-flowing Yampa River.

“One idea that I fully support is switching Dinosaur National Monument into a national park,” she said. “And hopefully Tri-State would partner with that effort and maybe use some of that water as we legislated that park to guarantee that we had the water moving west.”

Without local input into what happens to Craig Station’s water rights, Holloway worries it could hurt the Yampa, which is the plant’s current water source. Colorado has a long history of transmountain diversion, where water from the wetter Western Slope is diverted over the Continental Divide east to the populous Front Range.

“That’s the biggest fear, is they’re going to go into the headwaters of the Yampa, make a pipeline going over to the eastern slope,” Holloway said.

An unclear future

So far, Tri-State hasn’t tipped its hand on what it plans to do with the water. Duane Highley, Tri-State’s CEO, said at a news conference shortly after Craig Station’s closure announcement that his company already is fielding calls from interested buyers, but he didn’t elaborate as to who has inquired.

“When you look at a typical coal facility, it uses an enormous amount of water,” Highley said, “and the fact that that will be liberated and available for other reuse will be significant.”

A spokesman for Tri-State declined to be interviewed for this story. In an email, Lee Boughey of Tri-State said the company was not yet ready to delve into details related to Craig Station’s water.

“We’re focused on employee and community impact issues and support related to our New Mexico and Colorado plant closures, and with a decade to go in the operation of Craig Station, not in a position to discuss water issues related to the ultimate closure of the plant,” he wrote.

Craig Station uses on average 16,000 acre-feet of water each year. One acre-foot generally serves the water needs of two Colorado households for a year. A 2019 Bureau of Reclamation report showed thermal electric power generation in the Upper Colorado River Basin accounted for 144,000 acre-feet, or about 3%, of all water consumed in the watershed in Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Utah and parts of northern Arizona.

After flowing though Craig, Colorado, the Yampa River carves canyons through Dinosaur National Monument. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

“This creates a big opportunity to make water decisions more wisely,” said Gokce Sencan, who researched coal plants and their water rights while a graduate student at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The research was part of a consulting project for the Nature Conservancy – one of a few deep-pocketed environmental groups that are interested in buying water from retiring coal facilities and keeping it in rivers.

The Nature Conservancy receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which provides support for KUNC’s Colorado River coverage. The conservancy declined to comment for this story.

“It all comes down to who can negotiate with these plant owners and who can make a better claim or make a better offer,” Sencan said.

But the power company’s plan also is a factor, she said. If the company considers water a money-making asset, it could sell it off to the highest bidder. If it wants to do a good deed, it could listen to the local community.

“As a legal matter, the owners of the water rights, at least in Colorado, could do something else with them,” said Eric Kuhn, former head of the Colorado River District and author of “Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River.” “As a practical matter, there’s not much else they can do with them.”

Searching for a win-win

Tri-State has limited options with the water rights, Kuhn said. It could sell them to a local municipality, although communities along the Yampa River, like Steamboat Springs, Hayden and Craig, likely wouldn’t be able to use that much water all at once. Tri-State could offer them to local farmers, though most of the easily irrigable land already has been irrigated for a long time.

They could turn them into so-called in-stream flows or sell them to a user outside the Yampa River Basin, such as a Front Range city. Kuhn said any project proposed to pump Craig Station’s freed-up water more 200 miles to the east would face significant political pushback and a multibillion dollar price tag.

These coal closures also have implications for broader Colorado River management, Kuhn said. The recently signed Drought Contingency Plans require water leaders in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico to begin exploring a conceptual program called demand management, where in a shortage, water users would be paid to use less. Coal plants using less water would alleviate the situation.

“What it’s going to do is take the pressure off of these states to come up with demand management scenarios,” he said, “because where does that water go? It’ll flow to Lake Powell.”

Colorado is the only the state allowed to hold in-stream flows, in which water is kept in the river channel for ecological benefit. Private entities, including environmental groups, aren’t allowed to hold such rights.

“Converting (Craig Station’s) rights to in-stream flows or to recreation rights that can be legally protected, I think is a potential win-win for the community,” Kuhn said.

Maegan Veenstra and her husband run Good Vibes River Gear in Craig, Colorado. The town’s boom-and-bust history is tied to mining, she says, and it’s time for a transition to a recreation-based economy. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

Maegan Veenstra of Craig is among those looking for a win-win. On a snowy February day, she dodges rolls of woven, plastic fabric as we walk through her new storefront along the city’s main drag. She and her husband run Good Vibes River Gear, where they manufacture storage bags for rafters, kayakers and paddleboarders.

“We just want to help the economy diversify,” Veenstra said. “Plenty of other people from other areas have totally gotten it and are just flocking to their rivers. But there’s a slow movement here.”

She said Craig is starting that transition from mining to recreation.

“It’s been a boom and bust town for a long time. It’s time to just kind of get away from that and be just a steady growing town,” she said.

If the community is ready to double down on a new persona as a tourist destination, Veenstra said the decision is simple: Leave the water in the river.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.