Gaurav Sant, leader of the UCLA team seeking the $20 million Carbon XPrize, has been working with his team for five years developing CO2Concrete. It’s made using cement that has been mixed with mineralized carbon captured from the flues of industrial plants. (Photo courtesy of UCLA)

SANTA MONICA, Calif. – Scientists are racing to develop a concrete solution to the planet’s ever-growing greenhouse gas problem by actually trapping mineralized carbon dioxide in concrete. A UCLA research team hopes to win the $20 million Carbon XPrize with an innovation that aims to reduce some of the 37 billion tons of CO2 that are released around the globe each year, according to a 2018 estimate.

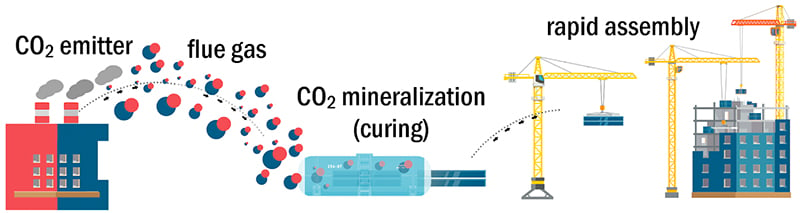

The team’s concrete wouldn’t absorb CO2 already in the atmosphere, but it would take industrial CO2 emissions before they reach the atmosphere and cure them into concrete blocks that trap the carbon within.

The UCLA team is one of 10 that have made it to the final round of competition for the Carbon XPrize, a race to develop sustainable technology that could help reduce carbon emissions. Nearly 40 competitors from all over the world have been in a race for the past two years, and the winner will be announced this fall.

Even if UCLA falls short, team leader Gaurav Sant said its product, CO2Concrete, will be in limited use this year.

“What we’re trying to do is develop a material which has the potential to be able to completely remove that specific type of emission from the production of Portland cement,” said Sant, a UCLA professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Portland cement is the main ingredient of concrete and the main contributor to carbon dioxide emissions from the production of concrete around the world. In 2018, the U.S. used about 100,200 metric tons of cement, which is the powder used to make concrete. In Arizona, more than 3,600 cement industry workers contribute $3.4 billion to the state’s economy, according to the industry’s trade association. Portland cement, which consists of calcium, silicon, aluminum, iron and other ingredients, is produced at plants in Paulden, Clarkdale and Rillito.

The UCLA team’s ambition is to remove all CO2 emissions from concrete production. So far, it has reduced emissions by 75%.

“We want to be developing technologies that have the ability to change how we live in this world and how we produce things in this world,” Sant said.

CO2Concrete uses calcium hydroxide to create a type of cement that would reduce carbon dioxide emissions through the process of reabsorption. First, carbon that industrial plants release in flue gas is collected and put into a chamber with concrete blocks. The emissions are then cured into the blocks and trapped inside.

Graphic courtesy of UCLA

CO2 emissions from cement account for about 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. The U.S. produces 13% of the world’s total CO2 emissions, but concrete is to blame for roughly 1% of those emissions.

Sant and his team have worked to keep CO2Concrete in the same price range as Portland cement because of the conservative culture of the industry, which makes it difficult to sell a sustainable product if it’s more expensive.

“You aren’t really going to be able to sell a greener material if it’s more expensive,” Sant said, “and so we’ve been very focused on the idea of ensuring an equivalence of cost.”

Despite the seemingly obvious benefits of having a sustainable form of concrete, the product has not yet been tested on a larger scale. The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine estimate that converting carbon could, at most, mitigate 15% of global emissions, according to a 2019 report.

Some experts question how realistic it is to expect success from innovations like those in the XPrize competition, considering the severity of the greenhouse gas problem.

Allen Wright is the executive director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State University and has done research about reducing CO2 emissions. Although UCLA’s innovation shows promise in battling greenhouse gases, Wright thinks there’s a pressing need for bigger changes to curb carbon emissions across the Southwest.

“I think that we’re probably 20 years beyond the point where it’s absolutely critical that we be concerned about it,” he said. “We’re too late, in other words.”

From Wright’s perspective, CO2Concrete would not specifically change CO2 emissions within the Southwest. Because of how mixed the atmosphere is, any reduction in emissions locally would be “quickly diluted by the rest of the atmosphere being swirled around,” he said.

Awareness matters, but Wright also is concerned about the lack of policies that have been enacted to tackle this issue. Putting pressure on policymakers to “enable and encourage research and development into carbon management technologies” is what’s needed, he said, adding that it’s “long overdue.”

For 25 years, XPrize Foundation competitions have invited researchers from across the globe to create products to build a more sustainable world.

The 2004 XPrize winners were tasked with creating “a reliable, reusable, privately financed, manned spaceship.” That team went on to license their technology to Richard Branson, who launched Virgin Galactic, one of the first companies to attempt to develop commercial space travel.

Marcius Extavour, the executive director of the Carbon XPrize, said XPrize chose carbon dioxide as this competition’s topic because of its contribution to the greenhouse effect and air pollution.

“Carbon dioxide is not the only gas and substance doing that, but it’s one of the ones we can control and it’s a crucial one,” Extavour said.

Competitions like the XPrize help to address areas of sustainability that may be under-researched, he said. The $20 million Carbon XPrize, which is funded by donors, allows the winning team to develop its product for the market.

“We thought by using an XPrize, (it) would be a way to really galvanize the whole community around the topic, attract some innovators, and hopefully achieve some really meaningful breakthroughs,” Extavour said.

Among the Carbon XPrize competitors, there have already been some real-world successes. Some of the products created are already available to be purchased, including watches made with carbon dioxide emissions.

“Carbon XPrize focused on CO2 conversion into materials because we wanted something that was a really audacious goal, something that was not getting enough attention and not being explored,” Extavour said. “It’s not the only solution we need but it’s one crucial one.”