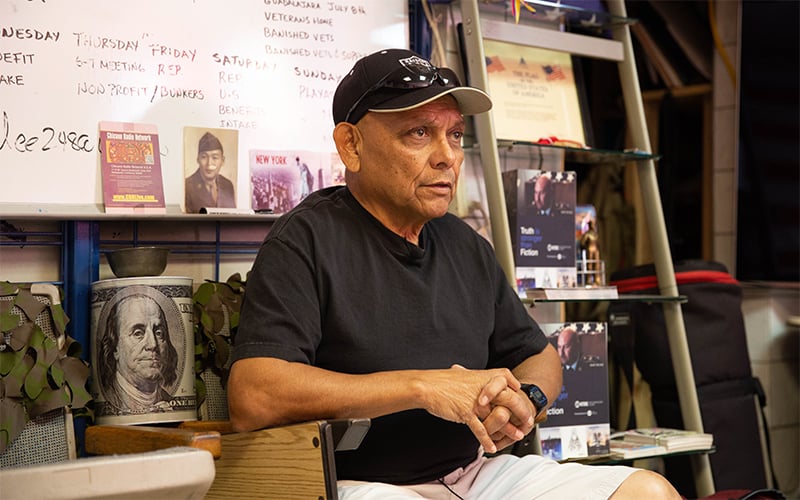

TIJUANA, Baja California, Mexico – Richard Avila was 17 when a military recruiter showed up at his home to persuade his parents to let him join the Marines. He enlisted in 1972.

Avila was shipped to the Philippines within months of turning 18. The Vietnam War was coming to a close, and Avila and other enlistees were to prepare for the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, which would soon fall to communist forces.

After his mission in Asia, Avila met up with military friends he knew stateside. But the men now were severely drug addicted. Succumbing to peer pressure, Avila soon became one of the thousands of Vietnam-era troops to return home addicted to hard drugs. He was discharged under “conditions other than honorable” after being arrested on base for drug possession.

“I carried my addiction into civilian life,” he said. “I never received any rehabilitation, which is actually part of the discharge procedures for addicts.”

For the next 30 years, Avila would struggle with drug addiction, and often had run-ins with the law. The charge that made him deportable was robbery. He was deported in 1996. Avila returned to the U.S. several times, and eventually served three years in federal prison before being deported a final time.

He never married and never had children, but his nieces and nephews, who lovingly call him “Uncle Richie,” are his world. “I hope they don’t find somebody else to take my place,” he said. “Hopefully, someday soon I’ll be able to be back playing in the backyard with them.”

Right now, he’s not pursuing legal action to return to the U.S. He doesn’t think it’s right to go home without his fellow soldiers. “I really don’t believe that they’re individual cases,” he said. “I just do as much work as I can here with the veterans so that we call all go back.”