PHOENIX – It’s late October but still too warm for fall. The sun pours through the open panels of the rose-colored walls of the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix, where men and women from different cultures and backgrounds are filing in for Friday prayers – jumu’ah, in Arabic.

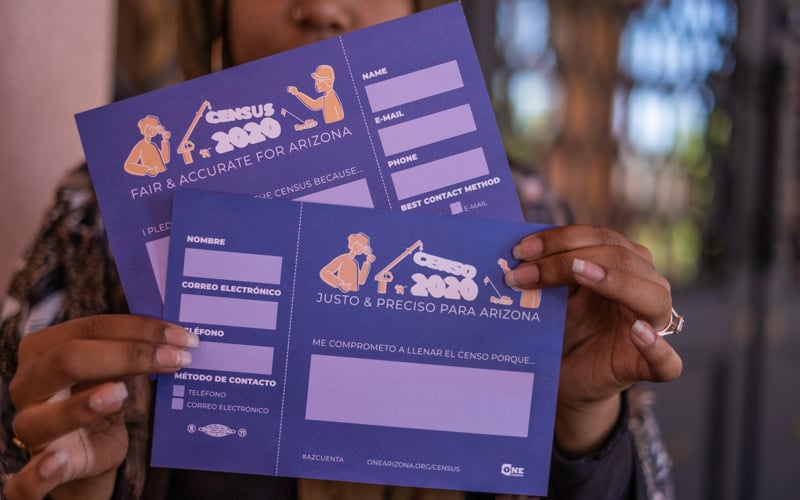

Inside, the sound of the athan, the Muslim call to prayer, reverberates loudly. Outside, by the intricate steel doors that guard the main entrance, two volunteers working for the Council of American-Islamic Relations, known as CAIR, hand small blue flyers to the worshipers who pass by, many of them Muslim refugees from countries in the Middle East and Africa.

The flyers read: “Census 2020, Fair & Accurate for Arizona.”

The 2020 census was supposed to include a new race category for people from the Middle East and North Africa. The idea was proposed during the Obama administration, after many years of pressure from members of a growing community asking to be counted as they think they should. But the Trump administration scrapped the plan early last year, a decision that advocates in Middle Eastern and North African communities say did not come with a convincing explanation. Instead, the administration decided to repeat the same racial and ethnic categories used in the previous census, in 2010.

That means many respondents from the region – usually referred to by its acronym MENA – will again check the box that reads “White, including Middle Eastern” in the 2020 census. The option seems far from ideal. To these respondents, checking a box that reads “white” does not mean they are treated as white Americans or benefit from the privileges that come with being white. They still are regarded as different. They still suffer from discrimination.

“Some other race,” a catchall category for people from many parts of the world who don’t see themselves in any of the options provided by the census, has become the go-to choice for Middle Easterners and North Africans who aren’t comfortable calling themselves white, according to an analysis of the 2015 National Content Test, which is used by the U.S. Census Bureau to define potential categories for future questionnaires. In an increasingly diverse country, the “Other” category has become the third-largest race group in the United States.

The Islamic Community Center of Phoenix is one of many mosques working to ensure Arizona’s Muslim community is represented on the 2020 census. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News)

But it has its problems. One is that it makes it harder to identify trends specific to certain communities, particularly health statistics, which are directly linked to race and ethnicity categories defined by the census. For example, a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality said collecting health data in the Latino community has been a challenge because many Latino respondents check “Some other race” on official forms.

For many Middle Easterners and North Africans, selecting “Other” on a government survey that is the constitutional base for important political decisions – from determining how many representatives each state will have in Congress to distributing federal funding – feels like negating their identity.

“We’re completely cut out of the picture when it comes to research on a variety of topics in this country,” said Jordan Harb, 19, who is half-Lebanese. “No one can tell if we’re being specific with what we’re going through because no one can track where we are.”

Since the first census in 1790, there have been many changes in the ways racial and ethnic categories are presented, for several reasons. Jeremy Vetter, an associate professor of history at the University of Arizona, said these have ranged from “changing ideas of race and ethnicity” to “empowerment of different groups of people and how they should be recorded.”

“It’s been a long, messy process,” Vetter said. “There isn’t one simple trajectory.”

For example, “black” disappeared from census forms from 1930 to 1960, only to be reintroduced in 1970 because of the wave of racial pride that had grown in the wake of the civil rights movement. “Korean,” a stand-alone ethnic category from 1920 to 1940, vanished for two decades, returning in 1970 in response to an increase in the number of Korean immigrants in the United States.

Although there won’t be any new categories for the 2020 questionnaire, the Census Bureau will for the first time make census forms available in 13 languages, including Arabic, which is widely spoken in the Middle East and North Africa. That’s possible because of another first: In 2020, respondents can fill out census forms online.

In a news conference in Phoenix in October, Timothy Olson, associate director of field operations for the Census Bureau, said 20% of the 900,000 people who have applied to work as recruiters for the 2020 census speak at least one language other than English. Hiring them is part of an effort to get as many diverse voices as possible to respond, Olson said.

“We need people who speak the languages of the neighborhoods that they’re going to work in,” he said.

Within Arizona, the bureau has partnered with mosques to reach out to immigrants from Muslim countries, including those in the Middle East — a “hard to count community,” in government terms, because its level of participation in the census is very low.

Lack of trust in the government is one reason Arab Americans have low response rates in the census, said Suher Adi, a policy associate at the Arab American Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded in 1985. They fear the information they give will be used in some form of surveillance.

“There’s a part of our message testing showing that there’s a fear of trust in the government – that is very understandable,” Adi said.

That’s why some community groups rooted in the Arab American community have launched outreach campaigns of their own. One of the largest is “Yalla, Count Me In” (“yalla” means “come on” in Arabic), a partnership between the Arab American Institute and American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, which are both based in Washington, D.C.

Adi said a main goal of the campaign is “making sure that everyone understands that the data that the Census Bureau is collecting is the most protected data that the government collects,” which is why an accurate count is critical.

Already, there are discrepancies. In 2017, the American Community Survey, an annual sampling of the U.S. population by the Census Bureau, estimated there were 1.9 million Arab Americans in the country. A survey by the Arab American Institute, meanwhile, found that number to be may be much greater – 3.7 million.

(It is also important to note that while all Arabs are from the Middle East and North Africa, not everyone from the Middle East and North Africa is Arab.)

Despite these efforts, for a lot of Middle Easterners and North Africans, filling out a census form next year will yet again be an exercise in frustration.

“If they don’t know the number of this minority group, then they tend not to listen to the problems that this group is facing,” said Usama Shami, president of the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News)

Take Usama Shami, the president of the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix. Shami, 57, who is of Palestinian descent, has struggled to find the right way to identify himself on government forms since coming to the United States from Kuwait in the 1970s.

In an interview, he recalled his time as a college student in rural Oklahoma, when he saw a fellow Palestinian get beaten up by a white student while putting gas in his car and heard of a Syrian student who had a kidney permanently damaged after two white men attacked him, seemingly for no reason.

One day while walking to a convenience store, Shami himself was the target of thrown beer bottles.

In every decennial census, under “race,” Shami picks “White, including Middle Eastern,” though, to him, the choice has never felt right. He said that nearly everyone around him considers him a minority, but that when his ethnicity is lumped with “white” in the census, it feels as though the U.S. government does not.

And that’s often a problem. When he travels with white co-workers, Shami said he is almost always the only one who is pulled aside for a secondary screening by TSA employees.

“I’ve been living here for 40 years, and when this experience does not bother others, to me, that’s a problem,” Shami said. “Because deep inside their minds, I feel that they really think that I deserve it. That they think that, yeah, it’s OK.”

Arabs in the United States were in court from the 1930s to the 1950s fighting for the right to call themselves white. Those were different times. Immigrants from Lebanon, Syria and Palestine seeking citizenship in the United States faced opposition from nativists, who favored greater rights for white, native-born Americans, according to Matthew Jaber Stiffler, research and content manager at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Many judges concluded that Middle Easterners were covered by the Immigration Act of 1924, which barred Asians from entering the country. Around that time, Stiffler said, Arabs began to hire lawyers to help them gain the right to classify themselves as white, using money raised by their community to pay for the legal fees.

They got what they wanted. But as the years passed, they began to realize that identifying as white may not be their best choice. Starting in the 1980s, Arab Americans realized that identifying as white didn’t mean they would be treated as white Americans.

These, Stiffler said, are some of the main reasons behind the push from the community to have its own designation on the census. One other is the diversity of the region. The Middle East and North Africa is composed of about 20 countries, covering a vast array of ethnic groups, which complicates questions about race and ethnicity.

Some of them may pass as white, but others do not.

Samia Muraweh, whose father is Palestinian, hesitates calling herself “brown” because of her light complexion. “It’s just, like, not being perceived by people in your own group and people outside of your group as a member of it,” she said. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News)

Samia Muraweh, 19, is Ukrainian and Irish on her mother’s side, and Palestinian on her father’s side. For her, the two sides are just not the same. And while she fully embraces her Palestinian identity, she hesitates in calling herself “brown” because of her light complexion.

“I think many people are resorting to using the term brown because, rather than more of like a physical trait, it’s more of like the ambiguity of ‘I’m not actually white, but I’m not black,'” Muraweh said.

Many younger Middle Easterners have embraced the term brown precisely because it’s ambiguous. To them, the word means a lot more than skin color. It denotes an identity.

“The way that my family has been treated and the way that my family lives in this country is not the equivalent of the majority of my peers who would consider themselves white,” said Jordan Harb, who is Lebanese. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News)

Like Muraweh, Jordan Harb can also pass as white because of his light skin. But that is not the case with a lot of his relatives on the Lebanese side of his family.

“I live with privilege, but everyone I care about doesn’t have the privilege,” he said. “I understand my family doesn’t have the same perks that I do.”

Still, on government forms, he said that he usually chooses “Other” because categorizing himself as white seems wrong. Inside, he feels as if he’s “always the foreigner on both sides.” His father was 10 when he fled Lebanon’s civil war in 1988 and moved to Salt Lake City, where he eventually met Harb’s mother.

“I always had a really hard time fitting myself into a category because I’m never Arab enough,” Harb said. “But I’m never white enough to feel like I have a part of my mom’s family.”

“I would like to be represented and (have) people acknowledge that I’m here. I’m not white and I’m not ‘other,'” said Maie Elkeshky, who moved to the U.S. from Egypt with her husband, Eslam Hag, in 2005. (Photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News)

For Eslam Hag and Maie Elkeshky, a married couple from Egypt, the question of race is just as complicated, but for other reasons. Hag, 37, is too dark-complexioned to pass for white. Elkeshky, 36, has a lighter skin tone than her husband, but, she said, calling herself white doesn’t feel right.

Since moving to the United States in 2005, they have often selected “Other” when that option was available. When it’s not, their next choice is “White, including Middle Eastern,” despite both of them saying that white doesn’t accurately represent their Egyptian identity.

If Hag could have his pick, he would identify himself as “Arab and Egyptian,” he said. He sometimes selects African American on government forms; on his father’s side, he is Nubian, the indigenous people of southern Egypt and Sudan.

“In terms of skin color or what I belong to, I feel more African,” Hag said. “If I am to be identified by a race, I resemble African Americans.”

For Elkeshky, finding a more suitable category for Middle Easterners and North Africans is important not so much because of how she and her husband identify themselves, but because of their three children. At school, they are registered under different racial categories. Elkeshky registered their two daughters as white because there was no other option, she said. Hag registered their son as black.

“I want them to be able to feel like they are well-represented in their community or in their workplace and they’re not ignored,” Elkeshky said.

The Arab American Institute last year filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., to force the U.S. government to disclose internal documents detailing the decision that led to the exclusion of MENA as a category in the 2020 census.

It also filed an amicus brief this year when the Trump administration’s push to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census came before the Supreme Court, arguing that the question would lower the participation of ethnic communities that would fall under the MENA category, as well as other communities of color.

In the brief, the institute also challenged the government’s inclusion of a citizenship question and its exclusion of the MENA category, despite decades of advocacy and testing showing that the category would promote an accurate count of the Arab Americans and other ethnic communities who currently do not have a place on the census form.

Adi, the institute’s policy associate, said the bureau’s reluctance to add the MENA category in 2020 “seemed quite evident that it might have been politically motivated.”

Adi said the Arab American Institute hopes the lawsuit will help “get understanding” as to why the MENA category was abandoned last year “without any explanation as the research that went behind it and the advocacy internally in the bureau that went into it.”

The lawsuit is still pending.

Meanwhile, at the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix, Shami has welcomed volunteers and census workers on Fridays, a dedicated day of worship for Muslims, to talk about the importance of participating in the survey. On that warm October afternoon, the volunteers were handing out fliers and asking mosque-goers to write down their phone numbers and email addresses so that they can be reminded to respond to the census once the questionnaires are out.

Although one part of his ethnic identity will not be represented in 2020, Shami said he is doing what he can to make sure that as many Muslims as possible make their voices heard.

And it all starts in the mosque’s pink building next to the southbound lanes of Interstate 17, on the edge of one of the most diverse slices of Phoenix.