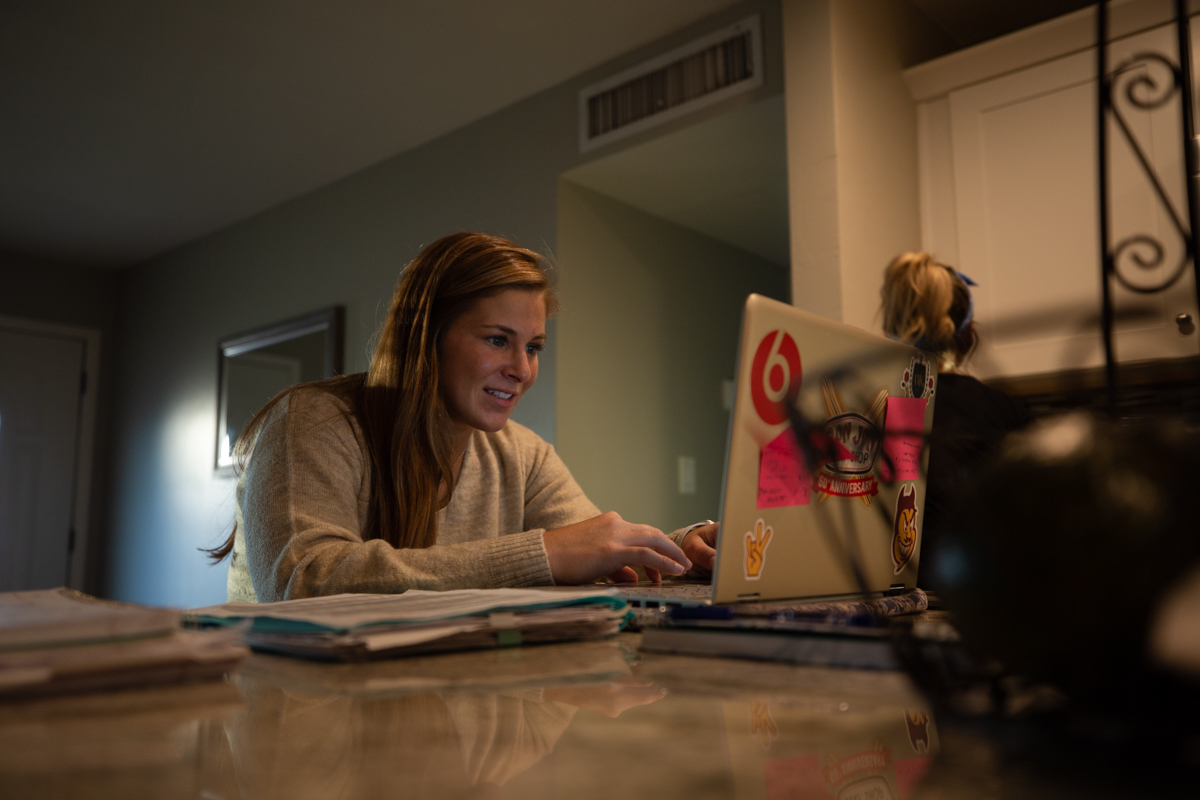

ASU Sophomore Marlee Smith is walk-on on the Sun Devil wrestling team. She’s only the second woman to ever walk on to the team, and she’s currently the only female wrestler on the roster. (Photo by Sarah Farrell/Cronkite News)

What’s next? As women’s wrestling grows, the landscape of opportunities changes

By Sarah Farrell/Cronkite News |

TEMPE – Trailblazing must be in Marlee Smith’s DNA. One day, while cheering on her dad’s football team, the squad found itself a player short and an unexpected opportunity arose for the 8-year-old.

“He looked at me and he said, ‘I’m taking Marlee,'” her mom, Christie Smith, recalled. “He took her off the sideline, threw pads on her and put her on the football field.”

It didn’t end there. She followed her male teammates to wrestling, a popular activity in her hometown of Wantage, New Jersey. She continued to thrive in the sport, which led to a difficult decision many female wrestlers face after high school: choose a school where she could continue to wrestle other women or try to join a men’s roster at a school that offered the major she wanted.

About 21,000 students participate in women’s wrestling, according to a 2018-19 participation survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations. That’s up 5,000 from the previous year. Additionally, 18 states now sanction women’s wrestling at the high school level, including Arizona and Smith’s home state of New Jersey.

Historically, there were two clearly defined paths for women to continue wrestling after high school. They could go to a university that had a women’s wrestling program, or they could try to claim one of the few resident-athlete spots at the U.S. Olympic Training Center (OTC) in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

These weren’t the only two options, but making a men’s roster is a feat that few female wrestlers had accomplished.

She had a decision to make.

The journey to collegiate wrestling

Smith had an instant connection with wrestling.

“She went in the room, and she fell in love with it,” her mom said.

From the beginning, it was the friendships and connection with her teammates that made her love wrestling. That, and beating up on the boys, Smith said.

Video by Mckenzie Pavacich/Cronkite NewsDuring Smith’s time in youth wrestling, there weren’t a lot of girls competing. She was on the boys wrestling squad at High Point High School and was only one of four or five girls competing in wrestling in the state of New Jersey at the time, her mom said.

“She was always the only girl in the youth program,” Christie Smith said. “She was the only girl at High Point High School when she wrestled from freshman to junior year. She would go to tournaments, and she’d be the only girl at a tournament.”

That changed after her junior year though, when the multi-sport athlete decided to drop out of other sports such as soccer and field hockey to focus on wrestling.

For her senior season, she transferred to Wyoming Seminary, a boarding school in Parkston, Pennsylvania, because the school had a girls wrestling team. It was the first time Smith competed on a girls wrestling team, solely against female wrestlers.

For Smith, there wasn’t a big difference between being on a men’s team and being on a women’s team though. Both “felt like family to me,” she said.

What made Seminary truly unique was the experienced coaches, Erin Vandiver and Adeline Gray, and the talent level of her teammates.

“Some of the best girls in the nation were there with me,” she said, “so I was getting really good training there.”

As she neared the end of high school competition, Smith knew she needed to make a decision. She could go the traditional route and accept a scholarship to compete collegiately in women’s wrestling. Or she could once again step off the beaten path, move across the country and gain access to the coaches and training partners that Arizona State had to offer.

Luckily, Smith had other female wrestlers who served as role models. About a decade earlier, Kelsey Campbell first set foot in the ASU wrestling room, even though she didn’t come to the desert specifically to wrestle.

“The reason I moved to Arizona in the first place was to help build a college ministry for the church I was a part of,” Campbell said. “I was an ASU student, and I was training at pretty much wherever I could find when I moved here.”

In 2006, she took the unprecedented step of trying out for the men’s team at ASU.

“At the time, I was kind of struggling with structure from a scholastic standpoint and a wrestling standpoint,” Campbell said. “I felt like, ‘If I try out for the team, I have nothing to lose.'”

Campbell became the first female wrestler to walk-on at ASU, setting the example for younger wrestlers such as Smith to follow.

Campbell cautioned that this isn’t the best path for every young wrestler though.

“It really depends on the athlete,” she said. “It depends on what your goals are. It depends on what you want your season to look like. If you want five to seven matches every week, then this is probably not the place for you. But if you want that extremely elite experience, being part of a Division I program, we do have some of the best coaches in the world here.”

Changing landscape of collegiate wrestling

Since the 2007-08 season, the Women’s Collegiate Wrestling Association (WCWA) has stood as the oversight committee for women’s wrestling. It encompassed schools from the NAIA, NCAA and NJCAA that wanted to field a women’s wrestling program and compete for a collegiate national championship.

The NAIA began to shift the landscape of collegiate women’s wrestling when it granted the sport invitational status in 2018. The sport is not solidified as a championship sport yet, but many schools competed at the inaugural NAIA Women’s Wrestling National Invitational.

After an initial application was submitted in 2017, the NCAA announced this summer that it would add women’s wrestling as well as acrobatics and tumbling to the NCAA Emerging Sports for Women program. Women’s wrestling could be contested as an emerging sport as early as Aug. 1, 2020. The sport reached the NCAA’s threshold of at least 20 varsity programs in 2019.

According to USA Wrestling and Wrestle like a Girl, there are currently 23 NCAA schools sponsoring women’s wrestling. To become a championship sport, there must be at least 40.

Additionally, female wrestlers have the option to wrestle at the club level for teams in the National Collegiate Wrestling Association (NWCA).

Sarah Hildebrandt, a member of the US World Team, chose the collegiate wrestling path. She competed for King University, in Bristol, Tennessee, from 2012-2015 winning two national championships along the way.

“When I was in school, there weren’t a ton of choices,” Hildebrandt said, “which meant it was possible for a lot of really talented women to all end up on the same team.”

Being on a team with other talented, driven female wrestlers was a positive for Hildebrandt. It sparked her Olympic journey from the time she was a freshman.

“Even to this day, half of our Senior World Team is all King graduates,” Hildebrandt said. “To get to train every day with women who were so impressive was absolutely rad, and great for my improvement. It was an intense practice room that I don’t think any other college matched at the time.”

Many of the universities that have women’s teams are small, with only a couple thousand students enrolled, in rural areas of the country. That limits the quality of facilities and coaches to which wrestlers have access. It also limits the academic degree options.

Near the end of her high school career, Smith had a number of offers to compete for schools in the WCWA.

“At tournaments, a lot of coaches came up to me, asking me to come visit their schools,” she said. “So I looked up wrestling schools and I didn’t like where they were located. They’re just in the middle of nowhere; small. Some didn’t have my major.”

Traditionally, the only option for women to wrestle in college was with schools in the Women's Collegiate Wrestling Association (WCWA). Many of the schools are small, and in rural areas of the country. For Smith, an important consideration was her desired major of Family and Human Development. (Photo by Sarah Farrell/Cronkite News)

Smith wanted to major in Family and Human Development and continue wrestling, so she knew she needed to find another option.

About a decade ago, the only other option that female wrestlers could choose out of high school was to apply to be a resident athlete at the OTC. That requires moving to Colorado Springs, living at the OTC full time, working with the coaches there and dedicating most of their time to training.

The atmosphere, especially during an Olympic year, is incredibly tense, said Hildebrant, who became a resident athlete at the OTC after she left King.

“The OTC is the best thing that has ever happened to me,” she said. “I have access to everything it takes to be the best athlete I can be.”

Hildebrandt, Campbell and Gray, a five-time world champion and one of Smith’s coaches at Seminary, all spent time at the OTC.

Campbell trained at the OTC for four and a half years after she left ASU. She had been beaten out at the World Team Trials in 2009, and realized she needed to make changes in her training.

“I had gotten out of it what I could get out of it at that point in my career,” Campbell said of her time at ASU. “It was time to transition and train around the best females in the world. If I was really serious about being the best in the world, that was where I needed to go.”

Growth of Regional Training Centers

Within the past decade, a shift has begun within American wrestling. Regional Training Centers (RTCs), often located near Division I programs, offer an elite training experience that is overseen and sanctioned by USA Wrestling.

“The RTCs have been fantastic for developmental wrestling in the United States,” ASU wrestling coach Zeke Jones said. “They’ve also been fantastic for women’s wrestling. [Female wrestlers] can train anywhere in the country that has a regional training center, and that’s mostly our best collegiate programs. So it gives our women a vehicle to train with the elite college athletes with aspirations of being the best in the world.”

Training at RTCs affords women access to experienced coaches such as Jones, an Olympic silver medalist who coached the 2012 U.S. Olympic freestyle wrestling team and remains active with Team USA’s program. RTCs also offer mentors such as Campbell, a 2012 Olympian, and world-class facilities.

For Smith, the decision to train at ASU was easy.

One of the biggest advantages for Smith training at ASU is having access to Division I facilities and coaches. She does all of the same practices and training sessions as her male teammates. (Photo by Sarah Farrell/Cronkite News)

“I wanted to train with elite athletes and have some of the best coaches, and I knew this was the place to be,” Smith said.

Campbell has met a lot of younger wrestlers, but meeting Smith stood out.

“She was not just like ‘Oh, she wrestles, and she wants to join the team,'” Campbell said. “[Smith] wanted to do something big. We just naturally clicked and became friends after that.”

Since Smith arrived in Tempe, she has in turn become a role model for other young female wrestlers.

“A lot of girls have been messaging me about coming here,” she said. “They always tell me they look up to me, and want to come here and train with me.”

In Tempe, the RTC is Sunkist Kids Wrestling Club. Art Martori, an ASU alumnus and former president of USA Wrestling, founded the non-profit in 1976. It has produced a number of Olympic and World Champions including Henry Cejudo, Jordan Burroughs and Helen Maroulis.

“We [provide the] assets necessary for them to do that,” Martori said. “That’s coaching. That’s travel. That’s getting them to the places they need to be in the United States and overseas. And getting them a stipend in which they can pay for their training, food and housing as necessary.”

USA Wrestling rules stipulate that in order for an athlete to qualify for an RTC, they must live within 250 miles of the facility and they must place at one of the qualifying tournaments. There are between 40 and 70 athletes around the country training through Sunkist at a time, Kim Martori, Art’s daughter and the day-to-day operator of Sunkist, said.

Jamill Kelly, a volunteer assistant at ASU and an RTC coach at Sunkist, said RTCs provide an important opportunity for female wrestlers. “To know that they can actually go to school there and still try to achieve their wrestling goals is something that I think is a positive,” he said.

Life of a wrestler at an RTC

For most of her freshman year, Smith was just an RTC athlete, but she walked on to the ASU roster at the end of that year. Being on the roster gives her access to the wrestling room, the full ASU coaching staff and the facilities, Kelly said.

“Being part of the team has given Smith a lot of confidence,” Kelly said. “She’s doing all the lifts. She’s doing all of the runs,” he said. “[The guys on the team] see her doing everything that they’re having to do.”

Jones views Smith’s presence as a positive for the entire team. “She’s a tremendous training partner for our guys,” he said. “She just adds to the collective strength of what we’re doing.”

Smith’s work ethic and intensity raise the level of everyone in the room, her coaches said.

Women’s wrestling is not a sanctioned Division I sport yet, which means Smith may never wrestle in an ASU singlet. But she still faces many of the same time constraints and demands as other collegiate athletes.

On her busiest days, Smith wakes up at about 6:30 a.m. She goes to morning practice or team lift, then goes home to eat breakfast and finish up homework before going to her three, in-person classes. Her classes end just before the daily afternoon practice session in the wrestling room. After practice, it’s dinner and more homework before she goes to bed at 10:30 p.m.

Although some do train and go to school, athletes do not have to be enrolled at a university to be a resident athlete at an RTC.

Campbell, now a veteran in the sport of wrestling, doesn’t have the commitments of being a student anymore. She earned her degree in Communications and Justice Studies in 2008. As a Sunkist athlete, wrestling is Campbell’s full-time job. She frequently travels between Phoenix and Colorado Springs for World Team camps, but she also travels around the world to compete with USA Wrestling.

US Wrestling on the international stage

On the sweat-soaked mats of Rio de Janeiro in 2016, U.S. women’s wrestling took a big step forward. Helen Maroulis delivered the country’s first Olympic gold medal in women’s freestyle wrestling.

The medal represented more than just a crowning achievement in Maroulis’ career, it illustrated the growth within the youth ranks of U.S. women’s wrestling.

“Helen Maroulis winning a gold medal did so much for girls who love the sport of wrestling,” Jason Bryant, who runs the podcasting site Mat Talk Online, said. “You can’t really put a price on what that meant.”

Source: International Olympic Committee & United World Wrestling

(Graphic by Sarah Farrell/Cronkite News)

The U.S. still sits behind countries such as Japan and China in the overall international medal count, but the landscape may be changing as more girls start to wrestle and continue training even after high school.

“The first Olympics [in 2004], when we got women’s wrestling into the Olympics, we won a couple of medals,” Art Martori said. “Now we’re winning gold and being a force. Japan is still there, but we’ve gone from hundreds to thousands to tens of thousands of women involved in women’s wrestling.”

There are more women participating in wrestling, and there are more opportunities for them to try; options that provide tailored fits for each wrestler.

Kim Martori equated the role of RTCs in wrestling to that of clubs in other sports such as basketball and baseball. It gives young athletes access not only to top facilities and coaches, but also training partners, nutritionists and mental health professionals. It provides the support and the knowledge base to become a professional wrestler.

For Smith, much like her mentor Campbell, training at ASU is a stepping stone to what she hopes will be a long career.

“My ultimate goal is definitely to be a world champion, make the Olympics, have younger girls look up to me as being part of something they can also do, and start a women’s wrestling program here at ASU,” Smith said.

Follow Cronkite News: Phoenix Sports on Twitter.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]