FLAGSTAFF – By next fall, the U.S. will be the only country to have left the Paris Agreement – an international accord signed by nearly 200 countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a bid to slow climate change. Representatives from those countries are in Madrid this week and next for the United Nation’s climate change conference to take the next steps in global climate action.

President Donald Trump in early November formally notified the United Nations that the U.S. – second only to China as an emitter of greenhouse gases – would withdraw from the pact.

That decision comes at a time when the United Nation’s latest report on greenhouse gas emissions finds that countries have “collectively failed to stop the growth in global GHG emissions, meaning that deeper and faster cuts are now required” to stay on track with the goals set in the Paris Agreement.

In September, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report that highlights the effects a changing climate is having on the oceans and the cryosphere – the frozen parts of the planet.

The report finds among other concerns, that sea level rise is accelerating as glaciers and ice sheets melt in the polar regions and mountains, and the ocean is warming. It suggests that the livelihood of future ecosystems at risk of the effects of climate change can be preserved by managing greenhouse gas emissions.

Northern Arizona University professor Ted Schuur was a lead author on part of the report that focused on polar regions. Schurr, who runs the Schuur Lab at NAU and is an expert on Arctic permafrost, was nominated two years ago to write about the carbon trapped in frozen soil and how that could contribute to climate change if it’s released.

Ted Schuur, a professor at Northern Arizona University, was a lead author on the United Nation’s most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which his lab contributed research to. (Photo by Chelsea Hofmann/Cronkite News)

“There’s all of this organic carbon locked up, and when that starts to get warmer and it thaws,” Schuur said, “it turns into these greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide and methane. Those are released back into the atmosphere, and that affects climate everywhere, including the temperatures in Phoenix.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines the Arctic as the area north of the Arctic Circle, about 66 degrees, 34 minutes north latitude. It includes mountains, tundra and the Arctic Ocean, and covers parts of Alaska and such countries as Canada, Greenland, Russia, Iceland and Norway. About 4 million people live in this northernmost region of the planet.

We recently talked with Schurr about his research, and below is an edited conversation on topics ranging from what his research shows about warming in the Arctic to how he became involved with studying climate change.

This interview took place Oct. 24. It has been edited for length and clarity.

What does the environment look like in the Arctic, and how is it changing as warming takes effect?

I do a lot of my fieldwork in Alaska, and (the) Alaska Region is partly within what we call the Arctic, north of 66 degrees north. Then also it contains the boreal region, the boreal forest. What’s very unique about it is that even though there’s a forest growing, if you dig into the ground, it’s frozen. That’s the permafrost. And that’s a wild feeling, where it can be in the middle of Alaska, you know, 75 or 80 degrees the air temperature, and you dig down one or two feet, and the ground’s frozen.

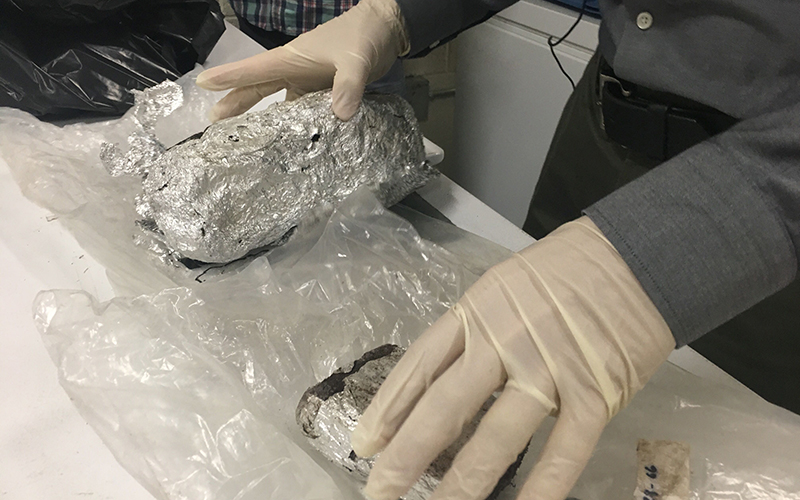

Elaine Pegoraro, a graduate student at Northern Arizona University who does research in the Schuur Lab, demonstrates the incubation systems used to calculate how much carbon is being released from the soil over time. (Photo by Chelsea Hofmann/Cronkite News)

Now one thing we know about the Arctic and the high latitudes in general is that their climate is changing about two and a half times faster than everywhere else. So as I go do this field work in Alaska, it’s both exciting – things are changing – (and) it’s awe inspiring because it’s a big landscape where people are small and the ecosystems are big. But it also has big implications for the whole world. So it really motivates me to collect the data and really make the measurements to document how and what is changing.

What can you learn about climate change from the soil?

Soils in Alaska and the Arctic are quite unique. They’ve been accumulating carbon, so this carbon is animals, plants, microbes – all these living things that have lived and died in these ecosystems have been stored in the soil. The reason it accumulates there is that the cold temperatures, this frozen ground, kind of locks it up. So this organic matter has been accumulating there for years, to hundreds of years, to thousands of years in some places.

Within that organic matter, you can start to look at pollen, you can ask which plants live there, you can ask which microbes live there, you can ask what was happening in these ecosystems of the past. So it’s both a storage reservoir of carbon, but it’s a little bit of a view into the history of ecosystems that came before. I think when you are looking back in the past and you realize that what we take for granted today hasn’t always been like this, it really helps you understand that the Earth could change and be very different than the world that we know and live in.

How did your research become related to climate change?

Once I sort of understood climate change as a societal issue and a global issue, it really changed the kind of science I was interested in. I became very interested in sort of knowing about an ecosystem of a place, but how that place related to the whole Earth system, and that was a perspective I didn’t have initially. I like to walk around in the woods, for example, but now I think about how this place is connected to places as far away as the Arctic by their cycles of carbon, water and nutrients.

What are some of the applications of the September climate report?

It’s called a consensus, and so this allows it to be used by many other people who are trying to move various decisions forward. I would say that it’s one of the best examples of the world science kind of brought together, sort of boiled down. … And then that allows people in policy that may not know every one of the details to take that forward and use it as they make decisions and plan for the future. So it really is a foundation for many different organizations and groups who are trying to think about what a future world will look like, and how do we plan for that?

Ted Schuur collects frozen soil samples from permafrost to determine how these ecosystems may respond to climate change. Here he opens samples in his lab at Northern Arizona University. (Photo by Chelsea Hofmann/Cronkite News)

What are some of the effects of climate change that make the problem urgent?

Every time you hear about one of these record weather events, it’s because the long-term climate is changing. We know that things likely won’t be the same, but we have a hard time predicting exactly where we’re going to end up. So what we know from climate change is that past addition of carbon to the atmosphere has already made changes happen. Some of these changes will continue to happen even if we stopped releasing all carbon today, but then we also see that we have big choices to make. So there’s time to act right now that will make a big difference to the future world that we all live in.

With the current state of the climate, how do you stay motivated with your research?

There has been a lot of communication and miscommunication about the topic, and I think it’s made it more challenging for people to know what to do. But I think at the same time, we all understand that if we do nothing, that’s probably not a great way to think about the future. And whether it was this issue of climate or anything else, we would like to have some plans for the future.

My particular feeling is that, you know, the Earth is going to continue to change, and the climate will change. But we have choices to make and we could alter the future that we end up in. So I hope that I can create some of the science that documents this change but also communicated to people that things that we do matter, things that we do make a difference, and we can choose the future world that we live in.

Video by Jordan Elder/Cronkite News