The secrets of ant cooperation could help ease congestion on roads and wherever there are dense flows of particles or bits of information. (Photo by Tworkowsky/Pixabay)

PHOENIX – Ants get a bad rap from picnickers, but drivers during rush hour might be able to learn a thing or two from our tiny six-legged friends.

The natural world teems with animals that move in groups, from flocks of birds to packs of wolves to schools of fish. But ants, like humans, belong to a more exclusive club: animals that routinely travel in congested, two-way traffic.

When ants find ample food sources, many species will lay down a chemical trail for other ants from their colony to follow. These trails can fill up quickly and involve hundreds of ants per minute.

To see how the social insects avoid gridlock, researchers turned to the European supercolony of Argentine ants (Linepithema humile), an invasive species that has established itself around the world, particularly in Mediterranean climates.

The scientists studied the insects as they crowded across a bridge to gather food and return it to the nest. To control ant density, the scientists varied the width of the bridge among 5 millimeters, 10 millimeters and 20 millimeters and the number of ants from 400 to 25,600.

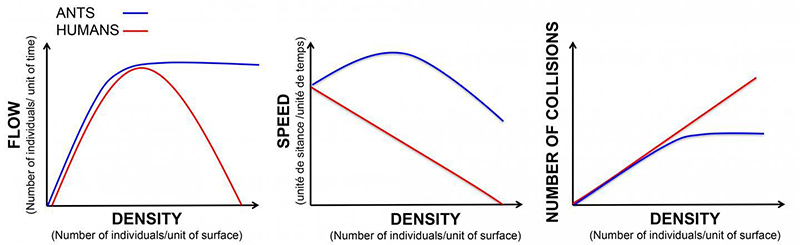

Co-author Sebastien Motsch, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, said the ants changed their speed and behavior to avoid snarls even when crammed into the densest of traffic.

Comparing traffic as a function of density in ants and humans. (Graphic by Audrey Dussutour)

“Surprisingly, it appeared that a traffic jam never occurred, so they always managed to nonetheless keep flowing somehow,” said Motsch, who partnered with researchers at Toulouse University in France and the University of Adelaide in Australia.

They said ants, “despite their behavioral simplicity, have managed the tour de force of avoiding the formation of traffic jams at high density.” Their research appears in the journal “eLife.”

Motsch specializes in studying how individuals interact and self-organize without a central authority to direct them.

Unlike human drivers jockeying for position on the road, ant “commuters” cooperate to accomplish a mutually beneficial goal, so optimizing their ability to forage while avoiding congestion is more survival skill than convenience or altruism.

Understanding how Argentine ants manage to keep on trucking through the worst jams could have widespread applications beyond traffic engineering, such as in fields involving dense flows of agents, particles or packets of information.

Ants in general appear to share beneficial reinforcement mechanisms that help them adapt to situations involving masses of bodies. Carpenter ants spread out to avoid trampling each other when trying to escape through a narrow door. Fire ants know how to stay out of each other’s way during construction projects. Garden ants excel at avoiding bottlenecks.

Motsch and his colleagues next hope to discover the mechanisms behind the Argentine ants’ self-regulation. But doing so could require tracking each ant’s behavior individually – no mean feat when observing tens of thousands of 2- to 3-millimeter-long creatures scurrying over and around each other.

“This kind of tracking is possible,” Motsch said, “but in an environment where it’s so crowded, it’s really challenging.”