WASHINGTON – Two years after the Trump administration announced plans to kill Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the program still has a pulse – though advocates worry about how long that might last.

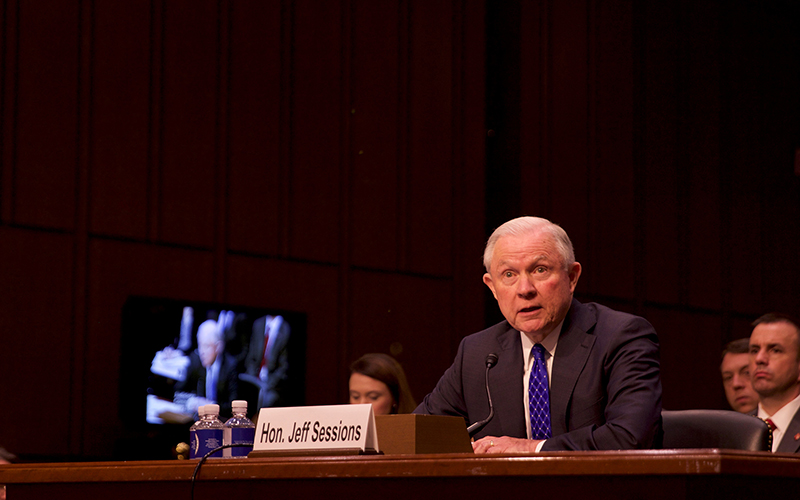

On Sept. 5, 2017, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Obama-era initiative to protect young immigrants from deportation would be phased out over six months, and that the government would stop accepting renewal applications after 30 days from those in the program.

Those plans were quickly challenged in courts, which ordered U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to keep accepting and processing DACA renewal applications as litigation continued.

No new applications have been accepted since Sessions’ announcement, but CIS has received and processed about 530,000 renewal applications between October 2017 and April 2019, according to the most recent data from the agency. And the overall number of active DACA recipients has been mostly stable, falling from just under 690,000 in fall of 2017 to about 670,000 active recipients as of April.

But just because renewals are still being accepted doesn’t mean eligible applicants should become complacent about their status, advocates say – after all, getting rid of DACA altogether is still the Trump administration’s goal.

“There’s definitely a sense of urgency, people are definitely being encouraged to renew now,” said Philip E. Wolgin, managing director of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress. “The message from the immigrant-rights community is, ‘Renew now, get it done, get your application in,’ because who knows what will happen?”

Given President Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign rhetoric on immigration, few were surprised when Sessions announced the end of DACA. He called the program an unconstitutional act of executive overreach by former President Barack Obama.

“The effect of this unilateral executive amnesty, among other things, contributed to a surge of unaccompanied minors on the southern border that yielded terrible humanitarian consequences,” Sessions said at the time. “It also denied jobs to hundreds of thousands of Americans by allowing those same jobs to go to illegal aliens.

“Simply put, if we are to further our goal of strengthening the constitutional order and the rule of law in America, the Department of Justice cannot defend this type of overreach,” Sessions said.

The program, started in 2012, defers the threat of deportation for two years for young immigrants who were brought into the country illegally as children and who meet certain criteria, such as pursuing an education or working and having a clean criminal record. DACA protection, which can be renewed after two years, also gives recipients the chance for other benefits, such as work permits and driver’s licenses.

Despite the court challenges, Sessions’ announcement did have one effect – DACA recipients rushed to renew in October 2017 to beat the threatened cutoff. Approximately 75,600 DACA recipients applied for renewal in that one-month window, according to a Center for American Progress report using CIS data.

But advocates worry that renewal numbers for that group seem to be lagging.

“Now, we’re hitting the two-year anniversary of that, and so we’re seeing a lot of people who still need to renew,” Wolgin said. “In October alone, there’s still nearly 56,000 DACA recipients that have to renew their status or face the possibility of losing their protection, so it’s a really big potential population.”

Wolgin said reasons for the drop are unclear and could be the result of a number of factors, such as recipients attaining a better immigration status in the U.S. or choosing to leave the country, cases in which they would no longer need DACA.

While renewals have continued, the DACA program has taken hits elsewhere. Besides refusing to accept new applications, CIS also ended advance parole, a program that let DACA recipients leave the country for various reasons – to visit a sick relative or study abroad, for example – and return without fear of deportation.

“DACA does not grant folks the ability to leave and re-enter,” said Jose Munoz, communications manager for United We Dream, a youth-oriented group advocating for immigrants’ rights. “The only way they were able to do that was through the advanced parole program.”

And for some applicants, the cost alone of applying for DACA renewal could prove prohibitive, Munoz said.

“The renewal fee is $495 to renew DACA, which is a pretty hefty amount for a lot of folks, especially if they’re working and they’re helping family or going to school,” Munoz said. Though advocacy groups like United We Dream can offer some assistance, some eligible individuals still may feel deterred from applying.

DACA will face its next major legal challenge this November, when the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear challenges to the lower court rulings that preserved the program.

“The Supreme Court case is not actually about the DACA program itself, so much that it’s about the way the Trump administration decided to end the program,” Munoz said. “Regardless of what the outcome is, the Trump administration will use this moment to … try to get Congress to increase funds to aid things like ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and CBP (Customs and Border Protection).”

Then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions in 2017 called for the end of DACA, which he called an unconstitutional “executive amnesty policy.” But two years later, Sessions is gone and DACA is still here. (Photo by Andrew Nicla/Cronkite News)

With the court not likely to issue its ruling until next year – or “right smack in the middle of the election cycle,” as Wolgin put it – expect DACA to become a campaign issue.

Advocates and policy experts expect Trump to only agree to protections for Dreamers if he can persuade Congress to allocate more funding toward enforcement actions, including detentions and deportations – a tradeoff that they say is not worth it.

“The Trump administration has said multiple times that he wants to deal fairly, humanely, with Dreamers, that he cares a lot about young people,” Wolgin said. “But when push comes to shove, the administration is still actively trying to take status away from these young folks.”

But Sessions said in 2017 that it is a matter of enforcing the law.

“The nation must set and enforce a limit on how many immigrants we admit each year and that means all can not be accepted,” he said then. “This does not mean they are bad people or that our nation disrespects or demeans them in any way. It means we are properly enforcing our laws as Congress has passed them.”

Munoz said the best thing for DACA might be that it becomes a political football over the next year.

“As we’re going into the 2020 elections, what needs to be really clear is that folks have the opportunity, through their vote, to reject the Trump administration’s agenda on immigration,” he said.