TEMPE – On nights when Phoenix Rising is playing, a cloud of red smoke often hangs in the air above Casino Arizona Field, home of the Valley’s professional soccer club.

Inside, behind the goal, supporters wave flags and reveal banners in a “tifo,” a choreographed display fans organize to demonstrate their support for the club.

The atmosphere of color and enthusiasm doesn’t tell the full story, however. It is also a tale about the intersection of fandom and politics.

What happened at a Rising game about two years ago is now being replicated at other stadiums across the United States, where fan culture is undergoing a renaissance.

Support beyond the team

Anyone who has ever watched Phoenix Rising probably is aware of Los Bandidos Futbol Firm. It is a passionate group camped behind the goal in the supporters section.

The groups members chant for 90 minutes in support of their team. They bang drums. They jump up and down. And they drink beer, especially on dollar-beer night.

Los Bandidos also call themselves antifascist, and have done so since their founding.

“A lot of it was born out of the socio-political climate of the time,” said Marco Medina, one of Los Bandidos’ founders. “There was a sense in the Latino community that things weren’t going well.”

“We thought, ‘Let’s provide a space where we can have a group where people don’t have to fear, or hide their cultural identities.'”

That antifascism manifested itself quickly in their support of the team. An image posted by the club from its 2017 preseason friendly at Grand Canyon University show flags bearing the commonly used logo of Antifascist Action, more commonly known as “antifa.”

The flags weren’t uncommon in the early days of Phoenix Rising, and were displayed alongside other left-wing banners. This was prominently highlighted after videos of Rising striker Didier Drogba were posted, showing him dancing in front of chanting fans as their “Refugees Welcome” flag sits in the background.

“At the beginning, we did focus on the antifascist symbolism,” Medina said.

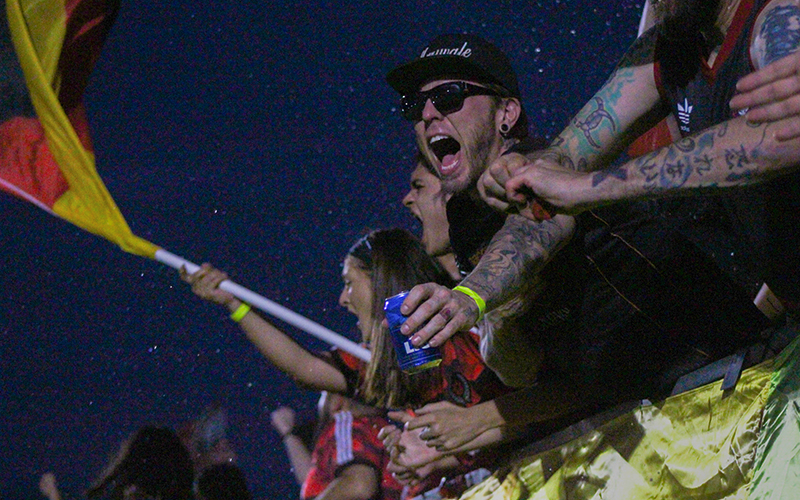

Rising fans are rarely fearful of being vocal, whether it’s about the team or a bigger cause. (Photo by Owain Evans/Cronkite News)

Their activism wasn’t limited to the stadium. When President Donald Trump visited the Valley in August 2017, Los Bandidos’ Facebook page posted an image of three individuals, at least one of whom was wearing a Phoenix Rising jersey, holding a “Goodnight White Pride” flag.

Controversy followed. A breaking point came in the form of a banner that included a crossed out swastika along with the words “Stop Racism” that was displayed along the front rail of the stands during a match in 2017.

“We weren’t trying to be edgy,” Medina said. “It was out of genuine concern about what happened in Charlottesville.”

Stadium security ordered the banner removed. Buoyed by a sense that if one flag came down, they all must come down, the group left that game at halftime taking all of their banners and boisterous support – with them. Afterward, they posted on social media, telling their followers that they would not compromise their anti-racist values.

Global perspectives

Los Bandidos’ attempt to bring politics into sport might be frowned upon in parts of the U.S. for crossing the wall-like barrier between serious issues and light-hearted entertainment.

Around the globe, however, their activism is far from uncommon.

In fact, it goes back to the 1960s. A series of popular protests hit Europe, and the protesters didn’t leave their gripes behind when they entered the sporting arena.

“So the argument is that the political activists in the streets took their paraphernalia from the streets into the stadiums, which is sort of where the ultras get their flags,” said Dr. Mark Doidge, a Senior Research Fellow at England’s University of Brighton.

Groups at clubs such as Germany’s St Pauli and Scotland’s Celtic, both left-wing, served as inspiration to Los Bandidos and others like them.

“Absolutely,” Medina said, “they were some of the blueprints we went off of.”

A foray farther into Eastern Europe reveals a different kind of supporters group, one on the opposite end of the political spectrum.

“There’s certain places where many of the groups would identify with nationalistic politics, but then equally, so do their governments,” Doidge said. “So it’s no surprise, then, that their fans would also be quite nationalistic.”

Yet the organized right-wing of the game, epitomized with clubs such as Lazio and those of Poland, has never particularly taken root in the United States, despite occasional controversy in cities such as New York.

“It feels like the situation in the U.S. is slightly different because of the range of sports,” Doidge said. “Most countries, football (soccer) is the number one sport and therefore you get the plurality of identities within football.”

That uniquely American spin on the game’s culture differentiates it from other parts of the world.

“That opens up a space where football becomes this interesting political space, because it’s a way of articulating your rebellion from those traditional American sports of baseball and American football and NASCAR, things you don’t really get anywhere else,” Doidge said. “At the same time, it’s also within this explicitly capitalist model, which is the clubs are businesses, whereas in Europe they grew out of everyday social clubs.”

Keeping politics out of sport

Phoenix is far from unique in bringing politics into U.S. soccer stadiums.

In recent weeks, supporters groups from Portland and Seattle have found themselves under fire for the use of antifascist imagery at games. Specifically, the use of the Iron Front symbol – a German emblem belonging to an anti-Nazi paramilitary group from the 1930s – has drawn the ire of league officials. Even on the field, player Alejandro Bedoya celebrated a goal by grabbing an on-field microphone and urging Congress to “end gun violence” – live on national television.

Yet those political actions, taking place on a large stage, can have unintended consequences. On the same weekend that El Paso grieved over a mass shooting committed by a man police believe posted an anti-immigrant manifesto, 12 people who identify with the Proud Boys – a group branded by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a hate group – reportedly harassed left-wing fans on their way to a Seattle Sounders game, the Seattle Times reported.

That threat of retaliation by right-wing groups isn’t alien to Phoenix.

“I used to be worried,” Medina said. Now, he’s come to live with the threat that extremists could pose.

“Whether organized or not, they’re always going to go out of their way to do something about people who are not like them that live in their neighborhood,” he said.

Left-wing groups across the U.S. have countered by doubling down at soccer venues. More banners have been hung up at games across the country, under a cause dubbed “A United Front.”

“Groups bonding together to spread the same message,” Medina said of United Front. “I don’t believe we’ve seen what we saw there before. We could have done with that earlier.”

They still face the challenge of dealing with the establishment that is Major League Soccer, which has a code of conduct for fans that bars political language and gestures in stadiums.

In a recent ESPN interview, MLS Commissioner Don Garber said stadiums “are not environments where our fans should be expressing political views, because you then are automatically opening yourself up to allowing counterviews.”

He added that he believes the Iron Front is political, rainbow flags are not, and did not provide a clear position on “Make America Great Again” hats that are a trademark of Trump supporters.

“Keeping politics out of sport is itself a political statement,” Doidge said, pushing further that drawing lines about what is and what isn’t political is also, in fact, a statement of politics.

“Nationalism, capitalism,” Doidge said, “it’s there in every stadium. You’ll see national flags, and America seems to be even more where nationalism is more obvious and yet completely invisible. There’s a national anthem. There’s flags. So politics is there. It’s just the assumption that nationalism is normal.

“Capitalism is everywhere. You’ve got advertising hoardings, commercial breaks and all these other things. It’s there, but it’s never discussed. So it’s very hard in organized sports to get rid of politics.”

For now, the battle of politics for the top flight of U.S. soccer continues.

Giving back to community

In the days following that 2017 game Los Bandidos abandoned, the support group started a process of reconciliation with the club.

“They reached out to us and tried to get our point of view, and we sat down with staff,” Medina said. Even Drogba was involved in the discussion, he said.

“They said that it could incite a reaction from the far right, and if anyone were to react, that’s on their hands,” Medina said.

When asked for comment on how the team draws the line on politics, a Phoenix Rising spokesperson pointed to the club’s fan conduct policy, which expressly bans “political or inciting messages” from being displayed in the stadium by anyone.

Los Bandidos came back for the next game, minus their antifascist flags. But they haven’t abandoned their desire to effect change.

“Though you may not see antifa symbols in the stands,” Medina said, “afterwards, it was a wakeup call. Part of activism is about outside the stadium, helping the community.”

To that end, Los Bandidos have since joined other supporters groups in organizing Prideraisers, pushing to raise money for LGBTQ+ causes in their local community. They’ve hosted a documentary screening, raising money for a border charity. They’re also working through the logistics of organizing an ongoing food and water bank.

“We need to be sincere about what we can do,” Medina said.

That change, from the Bandidos of old to the present, leaves a blueprint behind for MLS-supporting activists who may find themselves no longer able to protest inside the stadium.

“Now that the messages are not allowed (in MLS), what are people going to do now?” Medina asked.

“Give up on being a socially-conscious supporter, or take that outside the stadium?”

Connect with us on Facebook.