Dogs play a critical role down on the farm, and experts say they can protect livestock from wolves. (Photo by Annie Ropeik)

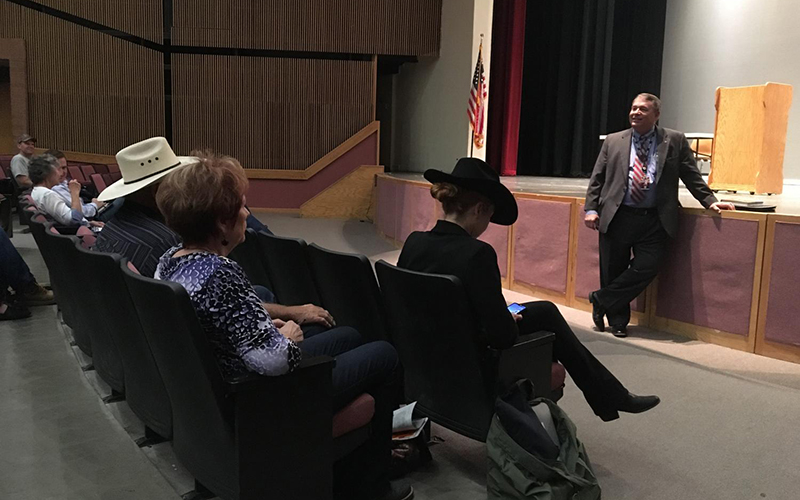

Mark Killian, director of the Arizona Agriculture Department, speaks at the Livestock Guardian Dog Forum in Eagar. (Photo by Casey Kuhn/KJZZ)

EAGAR – Farming often involves traveling long distances to remote areas to check on crops or livestock. And no matter what’s being raised, you’ll find many farms share one thing in common – a farm dog.

Working dogs also may be a tool in the ongoing battle between cattle ranchers and the reintroduction of the Mexican gray wolf.

Before we get into the fiercely debated Mexican gray wolf topic, let’s talk about dogs.

I have visited countless farms for stories about agriculture and rural issues. I always looked forward to it, no matter how long the trip or how early the call time. Farms are outdoors and it seems that there’s always something interesting going on in rural Arizona.

In fact, the first feature story I did when I moved to the state in 2015 involved dogs. I also tend to write those dogs into the story – especially if they’re particularly talkative.

Most of the time, the farm dogs I meet are working. For instance, on a fish farm east of Dateland, big white dogs that may have been Great Pyrenees help protect the goats on the farm.

Shepherds have worked with dogs to protect their flocks for decades in the U.S. but cattle ranchers have not. (Photo by Casey Kuhn/KJZZ)

At a half-day forum put on in early August by the Arizona Department of Agriculture, I learned that “big white dogs” actually is an umbrella farm-dog category that includes Great Pyrenees, Akbash and Anatolian shepherd dogs.

The Livestock Guardian Dog Forum was meant to educate ranchers in eastern Arizona and western New Mexico on how to use large dogs to protect their herds from the estimated 131 Mexican gray wolves that range in both states.

Keynote speaker Cat Urbigkit, a Wyoming sheep rancher and author, said American ranchers are behind their global counterparts in effectively using dogs.

“We’ve only used livestock guardian dogs in a systematic way in America for about the last 40 years, even though they’ve been used for thousands of years in other areas of the world,” Urbigkit said.

That would be in such countries as Spain and Turkey, where some of her dogs come from.

Decades ago, government officials began working with shepherds to use dogs as flock protectors, but cattle ranchers haven’t had the same benefit, Urbigkit said.

“The sheep industry in America has had four decades of experience in using livestock guardian dogs, so we have somewhat of a culture of using that now. But cattle producers, it’s just never been targeted for them,” she said.

Since the reintroduction of the endangered Mexican gray wolf in parts of Arizona and New Mexico in 1998, cattle ranchers have had to deal with their herds being targeted by the apex predators. In the first four months of 2019, federal officials reported 88 deaths of domesticated animals – almost as many as reported in all of 2018.

Urbigkit said there is no such thing as a peaceful coexistence between a rancher and a native wolf.

“Sometimes I cringe when I hear the coexistence thing because I heard someone say a peaceful coexistence, and I can tell you as a livestock producer who runs both sheep and cattle in wolf coexistence, it is not a peaceful coexistence,” she said.

Her dogs work as herd protectors – they will fight a wolf, sometimes to the death.

And though the dogs are well-loved, they are not pets.

Farm dogs are well-loved, but they are not pets. (Photo courtesy of Casey Kuhn/KJZZ)

“My guardian dogs, it’s like having the best hired hand ever,” she said.

About two dozen people attended the forum, which included a few testy exchanges. One man exasperatedly questioned a U.S. Fish and Wildlife official about the number of investigations the agency had done into wildlife killed by the Mexican gray wolf.

Mark Killian, director of the Arizona Department of Agriculture, said he hoped the forum would give ranchers a tool to use in their work.

“It’s having a negative impact on the ranchers, they’re losing a lot of livestock, so the purpose of this meeting was to give them some hope,” Killian said.

The federal government has indemnity payments for livestock producers who lose animals to wolves. Killian said his role is to help educate ranchers on what resources they have.

“We don’t have any money to do a wolf program,” he said. “So everything we do on this, we just kind of cobble together. We borrow employees from different parts of the divisions to put a team together and we work, and we do a lot of work on our own.”

Teresa Trujillo, who attended the forum, said she started keeping Anatolian shepherds on her property in the White Mountains when she considered raising small farm animals.

“I called our ag extension agent in Apache County,” she recalled, “and his response was ‘Oh no, you don’t want to do that there, there’s too many predators.’ And I said, ‘Well, what if I bring an Anatolian shepherd up with me?’ And he said, ‘Oh, then we don’t have to have this conversation.'”

Her dogs have grown in number, and although she doesn’t have livestock herself, a nearby rancher thinks her dogs have helped his business.

“The cattleman who runs his cattle on that open range says that since we’ve brought in the dogs, he hasn’t lost any calves. And he used to lose one to three a year in that area,” she said.

Trujillo thinks it’s about time American cattlemen start using farm dogs as tools against wolves. Because the Mexican gray wolf isn’t going away anytime soon.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

AlertMe