ALAMOS, Mexico – This is a “pueblo magico” (magic town), rich in beauty and cultural and historic significance. It’s also near an important ecological crossroads in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental.

The foothills are home to the northernmost tropical deciduous forest in the Western Hemisphere, and it’s a critical connection point between jaguars that roam Sonora and its neighboring state, Sinaloa, said Ramon Ojeda, who is the geographic information system coordinator on the nearby Reserva Monte Mojino.

“This is the natural protected area Sierra Alamos-Rio Cuchujaqui,” he said as we drove through a 230,000-acre, federally protected area. “Inside the federal protected area is Reserva Monte Mojino.”

The Monte Mojino Reserve is a 16,000-acre patchwork of former ranches pieced together to make a private reserve in Sonora. (Photo courtesy of Ramon Ojeda)

The reserve is a 16,000-acre patchwork of former ranches pieced together to make a private reserve.

“What we’re trying to do is bring the level of conservation to a stricter level than they have in the federal protected area,” Ojeda said.

Because even most federally protected land is privately owned in Mexico, the government can only provide certain protections. For example, cattle ranching and some mining are being allowed in the protected area. On the private reserve, Ojeda said, those kinds of human incursions are kept out.

Resident cats and visiting cats

Until a few years ago, he said, researchers thought jaguars only passed through here. But they started a monitoring program in 2014, and three years later, one of the camera traps snapped a photo of a pregnant jaguar, La Meche. That’s a sign of a resident population.

As we hiked through the dry undergrowth to the spot Meche was photographed, park ranger Alejandro Sauceda said the endangered big cat was photographed for three consecutive days in 2017.

Alejandro Sauceda (right), who has been a ranger on Reserva Monte Mojino for a decade, has never seen a live jaguar. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

“It was the first days of April,” he said. “And she was right here, by this little pool of water.”

Sauceda has been a park ranger on the reserve for 10 years, after the ranch he used to work on was purchased by Reserva Monte Mojino. He has never seen a jaguar, he said, but he knows they’re here, both residents and visitors passing through.

The Sinaloa corridor

“If connectivity between Sinaloan jaguars and the northernmost jaguars in Sonora is broken, in the worst-case scenario, the Sonoran jaguar could become isolated,” Ojeda said.

Cut off from genetic diversity, they would become vulnerable and eventually die out, he said, adding, “that would destroy the hopes of the United States that someday jaguars would return to Arizona.”

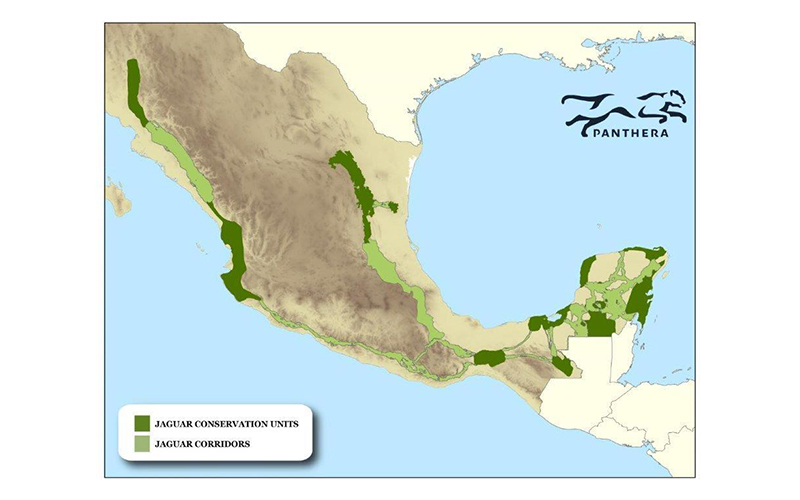

“The only corridor that currently has no population at the end of it is the one in Arizona,” agreed Howard Quigley, director of the jaguar program director and conservation science executive director for Panthera, a global wild cat conservation organization. He also was co-lead on a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service jaguar recovery plan released in April.

Quigley said re-establishing a breeding population of jaguars in the United States depends on three things in Mexico: protecting jaguars in Sonora, protecting jaguars in Sinaloa, and making sure those two core populations can connect.

(Map courtesy of Panthera)

“You need to have core populations that are well-protected,” he said. “And you need to have corridors between them to make sure that that lifeblood of gene flow is going to maintain those populations.”

The problem is, right now there are limited protections in the Sinaloa corridor between Reserva Monte Mojino and a jaguar reserve in central Sinaloa, said Quigley, who calls it a “no-man’s land between Mazatlan and Alamos.”

Another problem: President Donald Trump’s pledge to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Borderland corridors

Back in Alamos – a UNESCO World Heritage Site brimming with Spanish colonial buildings – Lydia Lozano drives around town showing off colorful murals of jaguars painted on the walls of schools, restaurants and other buildings. They’re part of the annual Dia del Jaguar, or Jaguar Day celebration, each October.

“You know, if you want to protect your jaguar population in Arizona, whether it’s one, two or three jaguars, you have to work with Mexico. And that’s reality,” said Lozano, Mexico director for Nature and Culture International, a San-Diego-based organization that runs Reserva Monte Mojino.

Corazon, a jaguar that was killed near the Northern Jaguar Reserve, graces a wall in Alamos, Sonora. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

The few jaguars that are seen roaming Arizona have to be able to cross the border to breed, she said. The Fish and Wildlife Service recovery plan included at least two places where jaguars can cross the border.

Many biologists would like to see many more borderland corridors safeguarded from additional border barriers.

“So you have this jaguar recovery plan made in the U.S., but everything has to be done in Mexico,” Lozano said.

“And it’s pretty obvious, but that’s how you know that we’re all connected. You’re talking about a species that has been forever connected through America. I’m just happy to find these partners that do understand that having a wall, it’s unnatural.”

The bigger picture

Lozano said for a long time conservation organizations had limited collaboration in Mexico because of stiff competition for resources. But she believes partnerships, whether they’re between the U.S. and Mexico, or Sonora and Sinaloa, are the best way to protect the jaguar across its northern range.

“I think NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) and also donors are shifting into the vision of protecting something bigger than just dots on a map,” she said.

Instead, they’re finding ways to share information and skills between groups and between isolated reserves, slowly stitching together pieces of the jaguar corridor.

“It’s at a very small scale compared to the jaguar corridor,” she said. “But it’s working.”

Jaguars numbers remain low throughout Mexico – there are only an estimated 4,100 in the entire country – and it could take decades for their numbers reach healthy levels, Lozano said.

Conservation and species recovery, she said, are a long-term commitment.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

AlertMe