SAHUARIPA, Mexico – A century ago, jaguars roamed much of the Southwest, including most of Arizona. Today, the only glimpses of the endangered big cats in the United States are caught on cameras just north of the U.S.-Mexico border.

In a recovery plan released in April, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said bringing jaguars back to the U.S. means protecting the population south of the border in Mexico, which is estimated at 120 animals. That’s what the Northern Jaguar Reserve in central Sonora is trying to do.

Saving big cats in Sonora

It’s late May in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental range. Dry grasses and gray-brown twigs crunch underfoot as biologist Miguel Gómez and his colleagues trudge up an overgrown trail to check motion-activated camera traps on the Northern Jaguar Reserve, a private protected area about 130 miles south of the U.S. border.

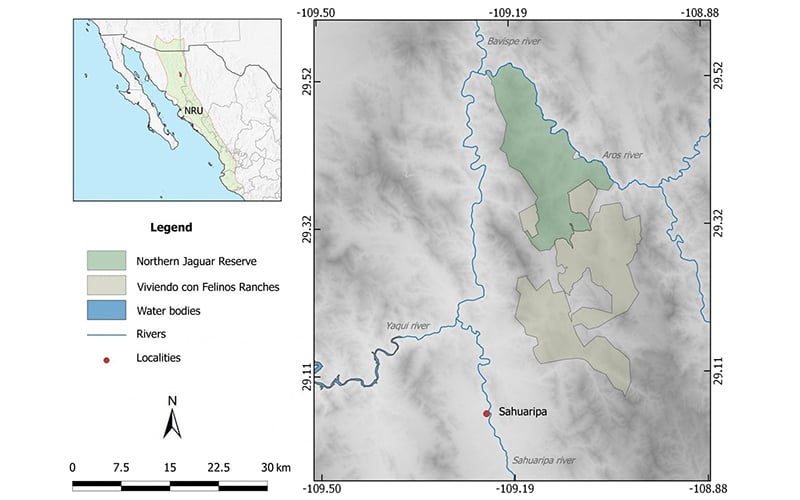

The Norther Jaguar Reserve was created in 2003 when the Mexican conservancy Naturalia purchased the 10,000-acre Rancho los Pavos in northeastern Sonora.

The cameras are tucked into hillsides and arroyos, and fastened to trees. Gómez clicks through photos of vultures, javelina, foxes and, most important, cats: mountain lions, bobcats, lots of ocelots. Then, finally, a jaguar.

“There it is, the jaguarón,” Gómez said, his colleague whistling at the sight of the endangered cat.

Miguel Gómez adjusts the position of a jaguar camera. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

Caught midstride, the jaguar’s unique pattern of rosette spots were illuminated by the camera flash as it strolled through a palm-shadowed arroyo just a few nights before.

“Just knowing that you’re walking in a place where a jaguar has been a day, two days, two hours, before is something not very many people have the chance to do,” Gómez said.

He has spent more than a decade tracking and studying jaguars in this region. But he’s still awestruck to walk in the footsteps of the huge cat.

“It’s something really special,” he said.

A diminishing species

Jaguars are shy, solitary animals with territories that can span hundreds of miles, Gómez said. But habitat loss, poaching and conflict with humans has meant both their numbers and range have diminished.

A century or so ago, jaguars roamed from southern Argentina all the way north into much of the southwestern United States, including parts of Texas, News Mexico, California and most of Arizona. Now, most U.S. sightings are in the mountain wilderness of southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

Both the U.S. and Mexican governments now consider Panthera onca an endangered species. But many biologists worry a proposed U.S.-Mexico border wall, as well as expansion and fortification of existing barriers, will threaten conservation and make it harder for jaguars to re-establish north of the border.

In its recovery plan, the Fish and Wildlife Service suggested that the best way to bring jaguars back to the U.S. is by protecting the estimated 120 jaguars that live in Sonora, expanding that population and maintaining cross-border corridors that jaguars can use to move northward.

Coexisting with big cats

Central to that plan are such efforts as the 55,000-acre Northern Jaguar Reserve, which was created 16 years ago by buying former ranch land and turning it into a haven for the northernmost breeding population of jaguars in the world. Here, jaguars and other animals can roam free without roads, mines, hunting or other human interference, Gómez said.

“The goal of the Northern Jaguar Project is to safeguard jaguars in this region,” he said. “And because the jaguar is an umbrella species, we’re protecting the rest of the plants and animals in the ecosystem at the same time.”

The 55,000-acre Northern Jaguar Reserve is 130 miles south of the Arizona-Mexico border in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

But it’s not enough just to buy up land for the reserve, he said. Jaguars live in and roam much larger areas. And once they leave the reserve, one of the biggest threats to the northern jaguar in Sonora is retaliation, he said. A jaguar kills a rancher’s cattle – or the rancher thinks it has – so the rancher traps and kills the cat.

“The perception here that the jaguar is a predator to cattle is one of the primary problems we have,” Gómez said.

So to break that cycle, in 2007 the reserve started Viviendo con Felinos, or Living With Cats, a voluntary program for local ranchers. If they allow biologists with the reserve to place and monitor cameras on their property, the reserve will pay them every time a picture of a cat is taken on their land. Ranchers also have to agree not to hunt cats or their prey, and reserve biologists work with them to manage their livestock in a way that discourages depredation, or cats killing cattle.

For ranchers like Diego Ezrré, it seems to be working.

Changing perspectives

Every week, Ezrré drives his well-worn 1989 Toyota 4×4 up the mountainside from his home in the little town of Sahuaripa to his 2,000-acre Rancho El Calabozo, just south of the jaguar reserve.

On a good day, the 45-mile trip takes him four hours, he said. It took us six, crawling up the rocky dirt road overlooking deep canyons and towering rock formations. It’s hot and barren at this time of year in this part of the Sierra Madre. But as soon as the monsoon storms start, everything changes, turning lush almost overnight.

Ezrre has been part of the Viviendo con Felinos program since the beginning.

“At first, the attraction was the money,” he acknowledged. “But most of the ranchers who are in the program, our perspective has changed. We realize that the jaguars aren’t such a threat. They don’t cause nearly as much damage as illness and other things.”

Diego Ezrré runs cattle on his land just south of the Northern Jaguar Reserve. He is part of the Viviendo con Felinos program, which helps protect the endangered cats. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

Ezrré calls the Northern Jaguar Reserve a “good neighbor.” Since the reserve blocked off the land to hunting and worked with other ranches to do the same, jaguars passing through his property are less likely to target cattle because there are plenty of deer and javelina, he said.

It’s that kind of change that has made the Viviendo con Felinos program popular, said Carmina Gutiérrez, a biologist for the Northern Jaguar Reserve.

“There is a big waiting list,” she said with a laugh. “At the beginning, in 2007, nobody wanted to work with us. But now they know that it’s better to have wildlife than to kill wildlife, so they are realizing they want to be part of this.”

Seventeen ranches covering more than 88,000 acres are part of the program, Gutiérrez said. That’s more doubled the area where biologists can track, study and protect jaguars.

But change is slow, she said, and a lot depends on the choices the next generation of cattle ranchers make for their land.

“We don’t want them to decide not to be a cattle rancher, no, but to be a good cattle rancher,” she said.

Hope for the future

As the morning bell rang at the local secondary school in Sahauripa, a group of kids ran across the street to a nearby basketball court to show off a mural they painted. Rolling green hills covered with trees, flowers, birds and, of course, a pair of jaguars.

“We want to protect the jaguars because if not they’ll go extinct, and we won’t see them. We’ll be left all alone,” said 11-year-old Claudia, one of a couple dozen members of the EcoGuardian Club.

The reserve hosts workshops and campouts where these students learn that having jaguars in their midst isn’t a threat but an asset. And it’s making an impact, teacher Ramón Córdova said.

“They have a different perspective than my generation,” he said. “Little by little, they’re learning that it’s something special, that their home is like a sanctuary for these animals, and that they should want to take care of them.”

Still, there’s a long way to go to fully protect the northern jaguar even just in this corner of Mexico, Gutiérrez said.

“The work to try to change the mind for the whole community will be very, very difficult, and maybe I won’t see the results,” she said. “Maybe that will be my son, my grandson, something like that. But I think we’re doing what we can.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

AlertMe