Havasupai Councilwoman Carletta Tilousi, Flagstaff Mayor Coral Evans and the Grand Canyon Trust’s Amber Reimondo, from left, backed the mining ban, while Mohave County Supervisor Buster Johnson opposed it. (Photo by Miranda Faulkner/Cronkite News)

Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Prescott, angrily challenged supporters of the mining ban proposed around the Grand Canyon, saying their claims of environmental harm from uranium mining amounted to “scare tactics.” (Photo by Miranda Faulkner/Cronkite News)

Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, said his bill would simply make permanent a current mining moratorium on 1 million acres around the Grand Canyon. The bill’s 100 co-sponsors include all five Arizona Democrats. (Photo by Miranda Faulkner/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Tribal and environmental officials urged House lawmakers Wednesday to protect sacred land and natural resources by supporting a permanent ban on mining on just over 1 million acres around the Grand Canyon.

The “Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act” would prohibit all mining in the affected area, but supporters were focused on the uranium mining that has a troubled history on tribal lands.

“Uranium mining has already poisoned and will continue to poison the springs and waters of my Grand Canyon home,” said Havasupai Councilwoman Carletta Tilousi at a House Natural Resources subcommittee hearing. “It will be poisoning the land, the plants, the animals and the people that live there, including all the visitors that come to visit the Grand Canyon.”

But critics attacked those claims as “scare tactics.” Uranium mining poses no more threat than the area’s naturally occurring uranium, they said, and the “ill-conceived” and “misguided” bill would cost the region billions in potential economic activity.

“You can have your clean air, clean water and mining too,” said Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Prescott, who grilled witnesses at Wednesday’s hearing. “It would seem to me that it would be better to take it out than to leave it in.”

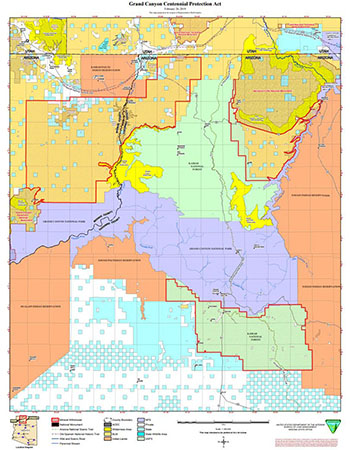

The Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act would make just over 1 million acres of federal lands – marked in red on the map – north and south of the Canyon permanently unavailable for mining of any sort. (Map courtesy Bureau of Land Management)

The bill would withdraw 1,006,545 acres of federal lands north and south of Grand Canyon National Park from mining. The Obama administration in 2012 instituted a 20-year ban on uranium mining on those lands.

But the Trump administration has been pushing for more-open mining policies, with the Commerce Department on Tuesday releasing recommendations to safeguard U.S. access to a list of minerals, including uranium, that are considered critical to the nation’s economy and defense.

Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, sponsored the bill that would make the Obama-era moratorium a permanent ban.

“It’s a simple piece of legislation. It takes what Obama did with the moratorium and makes that ban on mining permanent, simple as that,” Grijalva said at a Tuesday news conference in support of the bill. “It does not create a new monument. It doesn’t include any public land designations. It merely protects what exists now.”

Tilousi said the ban is needed to protect her village, which is on the floor of the Canyon, as well as the region that draws millions of tourists a year from around the world.

Tilousi said the Havasupai – which means “people of the blue-green water” – worry that mining will contaminate the waters that not only sustained them but been a source of tourist revenue for many years.

It’s not just her village, she said. The Colorado River is a primary water source for millions in the Southwest, in cities such as Las Vegas, Phoenix, Tucson and Los Angeles.

“According to the National Academy of Science there are no safe levels of consumption of ionized radiation, the only safe level is zero,: Tilousi said.

But Mohave County Supervisor Buster Johnson cited a U.S. Geological Survey report that said water samples from 428 sites in northern Arizona showed dissolved uranium concentrations were no different in areas with mines than in areas without.

“I can tell you if I had the slightest indication that mining would affect the canyon or the health of the people I represent I would be adamantly opposed to it,” Johnson said during testimony to the committee.

Both Johnson and Gosar stressed the potential economic benefits from uranium mining, which they valued at $29 billion. Gosar said mining could provide 2,000 to 4,000 jobs between Arizona and Utah, while helping the U.S. reduce its dependence on foreign nations, which provide 97% of the country’s uranium for nuclear power.

Johnson said sufficient environmental protections are in place even without the bill.

“The canyon and people are protected and the economic benefit of over $29 billion and the security of our nation is what’s at stake,” he said.

But supporters say any economic benefit from mining would be outweighed by its threat to the region’s tourism industry.

Amber Reimondo, energy program director for the Grand Canyon Trust, testified that uranium mining supports few and temporary jobs compared to tourism. She cited a National Park Service study that said the Grand Canyon brought 6.3 million visitors in 2018, who spent $947 million in nearby communities, supporting 12,558 jobs.

“Permanently contaminating the Grand Canyon threatens the loss of billions of dollars to the backbone of our regional economy,” Reimondo said.

-Cronkite News video by Julian Paras