Historically low water levels at Lake Mead outside Las Vegas prompted water leaders in Arizona and the other six Colorado River Basin states to negotiate a drought contingency plan last winter. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

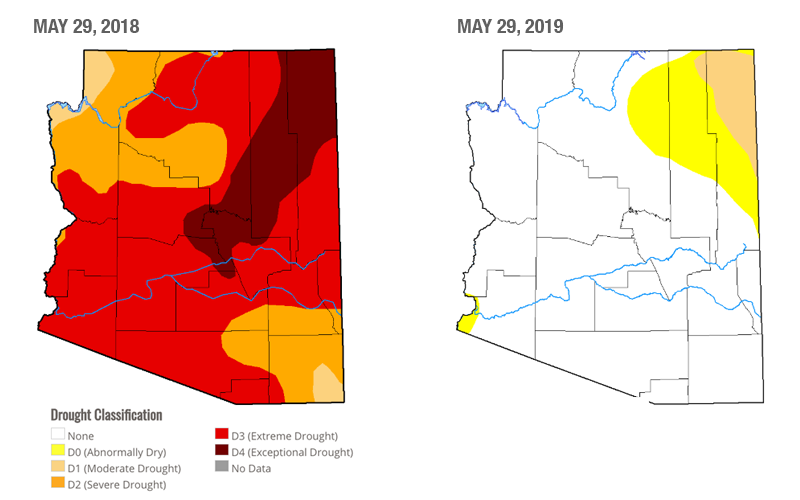

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor weekly report for late last week, only 20.5% of Arizona was showing moderate drought or “abnormally dry” symptoms. During the same period last year, 100% of the state in moderate drought or abnormally dry, with a majority of the state experiencing severe or extreme drought. (Source: U.S. Drought Monitor)

PHOENIX – The U.S. Drought Monitor recently reported that, for the first time in its nearly 20-year history, none of the contiguous states was showing symptoms of severe or exceptional drought. That report includes Arizona, as this year’s abnormally wet May helped push the state out of a 10-year drought period.

According to the monitor’s weekly report for late last week, only 20.5% of Arizona was showing moderate drought or “abnormally dry” symptoms. Data for the same week in 2018 found 100% of the state in moderate drought or abnormally dry, with a majority of the state experiencing severe (97%) or extreme drought (73.2%).

Richard Heim, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information, said the change was tied to this year’s wet spring.

“Rain and snow have been falling in the areas that needed it, so the drought’s contracted a lot,” he said.

Arizona is no stranger to downpours in the monsoon season, which runs June 15 to Sept. 30, according the National Weather Service, but heavy rain and snowfall in spring isn’t typical for the Southwest.

State climatologist Nancy Selover said the increased rain and snow came from winter storms over the Southwest that lingered longer and provided more moisture than in the past.

“Typically, that pattern stops in April, if we even get it,” Selover said. “Last year it was so dry, we never even got that pattern. … So it was really warmer than normal, really drier than normal. This year, we had what I would consider a more normal pattern.”

Heim said this kind of shift in drought status is normal for the desert. Although the U.S. Drought Monitor has been collecting data on drought since 2000, he said, such records as the Palmer Drought Index, with recorded data from as far back as the early 1900s, indicate that drought in Arizona ebbs and flows regularly.

Selover noted that the Drought Monitor’s map only reflects short-term drought, not long-term.

“In the western U.S., water resources is a long-term issue,” she said. “Reservoirs don’t fill in a year and aquifers don’t drain in a year or fill in a year. It takes multiple years that are dry or that are wet in order to change that.”

In late May, representatives from each of the Colorado River Basin states – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – signed the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan after almost six years of work to develop state plans to address the severe drought on the region.

Nearly 20 years of drought in the basin have caused the water levels of the Colorado River to drop, putting the reservoirs at Lake Powell and Lake Mead at risk of not having enough water to meet demand.

It can be difficult to precisely define a drought in a state known for being hot and dry. Marvin Percha, a meteorologist with the Phoenix branch of the National Weather Service, said drought is a “certain departure from what’s considered normal rain, precip(itation) or melted snow fall.”

So, Arizona and the Southwest’s standards for drought are far different from standards in other parts of the country that may be wetter or have the capacity to store large volumes of groundwater.

Selover said it can be hard to explain drought to residents of Phoenix, where water is accessed at the turn of a tap. Outside metro Phoenix, she said, Arizonans relying on groundwater more readily understand what’s at stake.

However, Percha said, wet spells like the recent one pose their own set of potential problems. Although ample rains have helped high-desert cities and forests reduce the threat of wildfire, the summer heat could spell trouble for the lower desert.

“Because of all the rain we’ve had in the winter, there have been a lot of grasses and what we call fine fuels that have grown, and now with the drier weather, they’re drying out,” Percha said. “That’s increased the fire hazard down in the lower deserts.”

National Weather Service meteorologist Marvin Percha says a “drought-free” Arizona is beyond human control. “We have limited water resources and so (what) we want to do is strive to conserve and use as much as little water as possible,” he says. (Photo by Melissa Robbins/Cronkite News)

He also said flooding could be a problem if wet springs become a long-term standard in Arizona, as reservoirs could overflow.

Selover said it’s more likely that years of drought and groundwater draws would collapse the soil, meaning aquifers won’t be able to store as much water as before. However, it could take about 10 more years of drought to reach that point, she said.

For Selover, the concern is flash flooding caused by the sudden heavy rain, similar to what Arizonans experience during monsoon season.

Mike Crimmins, an associate professor and climate science extension specialist for the University of Arizona, noted that seasonal allergies may stick around longer, with harsher symptoms, as a result of increased plant growth.

Crimmins said wet seasons are the optimal time to think about water conservation because drought is largely unpredictable.

“We can have this conversation, and then two months from now we’re in one of the worst monsoon droughts that we’ve seen or something like that,” he said. “That’s always a possibility. But I’m trying to be kind of optimistic here. … It really builds us some time to get the water situation under control in Arizona.”

Crimmins also said Arizonans should remember that one great wet season doesn’t mean climate change has been reversed or even slowed.

“This is a very local phenomenon for the Southwest and it’s been positive and beneficial, but we still need to be vigilant with water and keeping an eye on the temp(erature) trend in the long term as well,” he said.

Heim cautioned that Arizonans shouldn’t get too comfortable with the idea of a lush, wet climate in the future.

“I can guarantee you, because climate is cyclical, drought will return,” he said. “It’s like the James Bond movies: ‘James Bond will return’ at the end of the movie. Drought will return.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

AlertMe