After graduating from ASU’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Patty Talahongva went on to work in print, radio and television. (Photo courtesy of Vivian Meza)

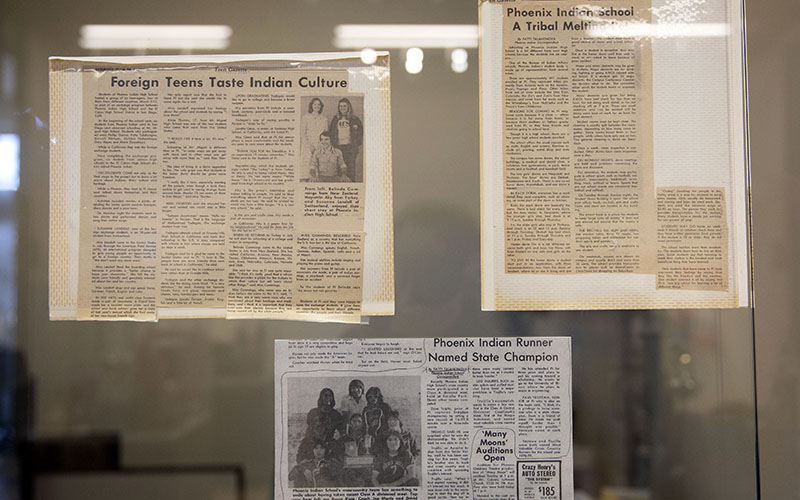

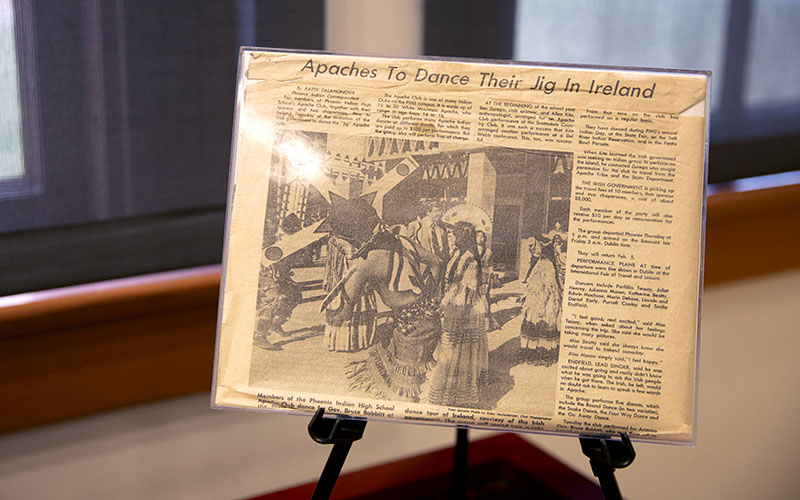

These are some of the first published articles Patty Talahongva ever wrote. She started as a correspondent for the Phoenix Gazette when she was 16 and now works as a part-time producer in local TV news. (Photo courtesy of Vivian Meza)

One of the first articles Patty Talahongva wrote for the Gazette is displayed at the visitor center at Phoenix Indian School. “That’s when I started understanding that I could actually make a living talking to people and writing their stories,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Vivian Meza)

PHOENIX – Born and raised on the Hopi Reservation, Patty Talahongva has always been sure of her identity as an indigenous woman — but she wasn’t always certain how she viewed religion. Raised a Catholic within the traditional Hopi culture, she began to question the religious practices of Hopis and Catholics after she became more familiar with history.

Patty Talahongva watches photos of her former classmates flash across a screen in an exhibit about Native American boarding schools she helped create at the Heard Museum. She attended Phoenix Indian School in the 1970s. (Photo courtesy of Vivian Meza)

She attended Phoenix Indian School, among Native American boarding schools with complicated pasts, for two years beginning in 1978. While there, she also found her calling: journalism. After an adviser recommended her for a position as a teen correspondent for the Phoenix Gazette, an evening newspaper, she fell in love with storytelling.

“That’s when I started understanding that I could actually make a living talking to people and writing their stories,” she said.

After graduating from high school in 1981, Talahongva went on to work in radio, television and print. Today, she’s a part-time television producer in Phoenix, but she returned to her former high school in 2013 as the curator of the newly renovated Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center. (The school closed in 1990, nearly a century after it opened in 1891 at Central Avenue and Indian School Road.)

She said the best part about the job is getting to uncover so much of indigenous history that can’t be found in textbooks.

“People don’t know our history, and sometimes our people don’t even know our own history. It’s not surprising,” she said.

Talahongva tells her story about how she grappled with religion and her faith, what life was like as a student at Phoenix Indian School in the late 1970s, and how she feels about the issues facing Native Americans today.

Did you grow up religious?

My dad is hardcore Hopi and my mom went to a Catholic boarding school, so my mom is also hardcore Hopi but has a Catholic school influence. When my mom and dad got married, they were married in the Catholic church and then they were also married in the Hopi way, so they had two wedding ceremonies.

Every Sunday my father would get up and brush our hair and braid it and get us ready for church, and he would always say, ‘Hurry up, your God is coming at 10 o’clock!’ I think about his perspective now, because Hopi (faith) is on every day, our creator is around us everyday. It’s not like, ‘Oh, 10 o’clock, time to pray!’ So I was raised in both ways, and then at one point I realized as an adult that I was born Hopi, and that’s my way. I’m not a great Catholic and I’m not a great Hopi because I’m not there for all the ceremonies. I just decided if I was going to be bad at religion, I should be bad at least with just one, not two.

I don’t consider myself Catholic at all. My mom raised us in the Catholic church but also Hopi. In her mind, she has reconciled it. I don’t know how, but that works for her. For me, I can only wrap my head around one, and that’s Hopi because that’s what I was born into. What’s interesting about religion is that tribes do not believe in conversion. We don’t practice it and we don’t force our way onto other people. We expect that you have your own way of worshipping, and we respect that. Go about it how you believe. We’ve never gone to war over religion; we don’t do that. I believe that we’re the true practitioners of freedom of religion, because we don’t force our way. We truly have respect for other people’s religions, their way of worshipping. No one has to fight over anything.

How do you reconcile being raised Catholic while also practicing the traditional Hopi way?

The Catholic church preaches about a jealous God, and the Hopi don’t see the creator as being like that. It was really hard trying to understand God’s wrath. Why would God be mad at you? Of course we’re mere human beings and we’re going to fall off and make mistakes, but I don’t think we have to worry about incurring the wrath of God. This idea of what is good, what is bad, the idea of confession and absolution, it just doesn’t make any sense.

Switching gears a bit: Were you forced to attend Phoenix Indian School?

When people ask me if I was forced to come to school here, I ask them to define “force.” Here was the scenario: In 1978, my tribe didn’t have a high school on its reservation, so I had no option. I had to come to boarding school. We didn’t have a high school on the reservation and we didn’t have a junior high, so all the kids were going off to boarding school. That’s what we had to do, too. So, no, government agents didn’t come up and round us up and forcibly remove us from our homes, but on the other hand, there was no other option other than to drop out of school. For my family, that wasn’t an option.

Did you encounter culture shock going from the reservation to Phoenix Indian School?

Yes, in the sense that I had been going to public school off the reservation where the majority were white with some Mexicans, no Asians and no African Americans, so then coming to a boarding school that was nothing but American Indians, that was a culture shock, even for an Indian.

You don’t know every single tribe, you don’t know their languages, and all of a sudden you’re sharing a room with somebody, so that was hard. It was exciting, but it was hard, and getting to know the little protocols of each tribe was different.

When you came to the school, were you allowed to speak your own language and embrace your culture?

Here at Phoenix Indian, towards the end of the school’s life, culture wasn’t repressed. In fact, when I came to school here we had the Pow Wow Club, the Hopi Club, we had a Miss Phoenix Indian pageant. People were feeling more free to express themselves and speak their languages. When I came here, everyone was speaking their languages, and that was really cool because I had never even met the Quechans, who are from Yuma. To hear people speaking in their languages was really cool because they were languages I had never heard before and to hear people conversing was cool. So yes, very much so, I would say.

We shared culture and we shared language. Everybody across campus knew how to laugh and tease in Apache and in Hopi. There were shared words that everybody knew what they meant. So that was fun to have that melding of culture. You could insult someone in Apache or in Hopi and everyone knew what you were saying because it just became part of the school’s language.

Did your views on religion change when you started school here?

I don’t think so. Growing up, I was fortunate because I saw our traditional side and our Catholic side, and then I lived in a town with a high population of Mormons, and then some Baptists and Mennonites, so I was around a lot of different faiths.

Is there anything else you would like people to know about the school or about you?

I think that we don’t teach this history, and I think it’s really important to understand it and to know about it. Our stereotypes as American Indians, they’re pretty strong and they’re pretty negative, so where do they come from? Alcohol is very much a European tradition, it’s very much a part of their cultures. It’s not for Native Americans. We don’t have happy hour, most of us don’t even have a fermented drink. That’s all new to us, and yet alcohol has devastated our people. It’s a foreign substance and idea, everything that’s not our traditional ways, and we’re reeling from the after effects of alcoholism in generations. I think that needs to be taught.

Our stereotypes are drunk and lazy, but no, that’s not who we are. But it’s the perception you see out there, and that’s really sad. Our people built the pyramids, our people were navigating the stars. Even teepees are aerodynamic, not even the wind will knock it down. A teepee will stay in its position because of the aerodynamic way it was built, and that’s indigenous intelligence.

Vivian Meza is a former Cronkite News reporter and wrote this story for her Arizona State University honors thesis, a project posted on her website that explores the intersection of Christian and Native faith.

Connect with us on Facebook.