Amy Love, deputy director of government affairs for the Arizona Supreme Court, said a large number of offenders coming into state prisons are brought in on technical violations stemming from prior convictions. (Photo by Hailey Mensik/Cronkite News)

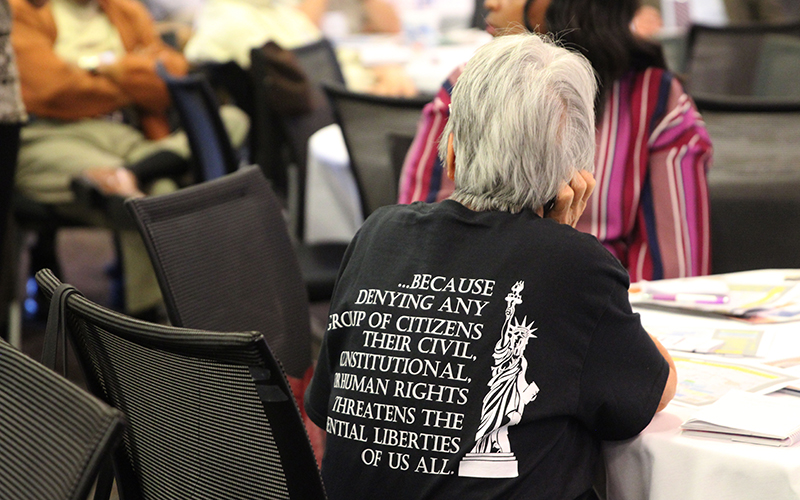

Reforms to slow the revolving door of the state’s prison system were discussed at an Arizona Town Hall in April. (Photo by Hailey Mensik/Cronkite News)

TEMPE – Officials and experts are exploring a vexing question about the revolving bars of the criminal justice system: How can we stop people from ending back in prison?

Arizona has the fourth highest incarceration rate in the country, according to speakers at an Arizona Town Hall earlier this month. The Arizona Department of Corrections houses 41,804 inmates.

That costs taxpayers more than $1 billion a year, including for repeat prisoners – 18 percent of those released return to prison within six months.

Investing in more opportunities for offenders to get jobs after release, along with other resources to help settle back into society could help slow the revolving door, presenters said. They also recommended hiring more parole officers and reducing or eliminating sentences to keep certain violators out.

Charles Ryan, director of the Arizona Department of Corrections, said former inmates’ access to meaningful jobs is key to keeping them from returning to prison. (Photo by Hailey Mensik/Cronkite News)

The corrections department aims to reduce recidivism, or the rate of those who return to prison, by 25 percent in 10 years, according to director Charles Ryan. He said inmates’ access to meaningful jobs is key and employers should consider the untapped labor pool.

Ryan said Hickman’s Family Farms is a good example, which works with the Department of Corrections and employs about 400 male and female inmates. The company hires many of them after prison, Ryan said, and even built 40 studio apartments on its property to alleviate housing issues for former inmates who work there.

Tara Jackson, president of Arizona Town Hall, said the state lacks enough halfway houses because neighbors resist having convicts nearby, fearing increased crime. That’s a growing barrier to helping former offenders assimilate.

“In Maricopa County, it’s almost impossible to open up re-entry centers,” Jackson said.

“It’s hard to reintegrate if you can’t come back to where your support system is, you can’t get a job, and there’s no housing for you.”

Amy Love, deputy director of government affairs for the Arizona Supreme Court, said a large number of offenders coming into state prisons are brought in on technical violations stemming from prior convictions, such as dirty drug tests or missed visits with parole officers.

“We need to make sure folks aren’t being sent to prison unnecessarily,” Love said, recommending bolstering the budget to hire more parole officers to monitor people convicted of minor, non-violent crimes.

Bills pushing criminal-justice reform this legislative session have gained little traction, including House Bill 2270, which would have allowed inmates a chance to reduce their sentences by completing education and treatment programs. But the bill failed this session.

The laws proposed were too broad said Donna Hamm, executive director of Middle Ground Prison Reform. Instead, she said reforms should be incremental and centered on shortening the sentences of certain kinds of offenders. Also, she said, it makes sense to use resources on prisoners who want to change rather than career criminals.

“Some people go to prison because it’s the cost of doing business as a major drug dealer,” Hamm said. “That person, of course, has to be interested in personal change and growth, and frankly, not every person who goes to prison is interested.”

“We have to have a classification system that separates the people who want to change and will work on it from those who just want to do their time,” she said.