WASHINGTON – The director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources told a Senate panel Wednesday there is an “urgent need” to authorize a multistate drought contingency plan for the Colorado River basin.

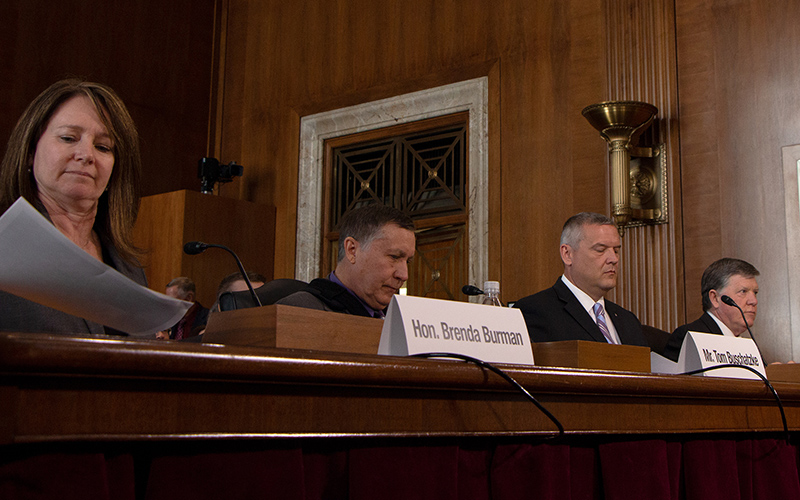

Tom Buschatzke was one of several state and federal officials pressing Congress on the plan, years in the making, that is designed to head off a potential water “crisis” in the region and help settle disputes over water allocations if the Colorado does drop to crisis levels.

Despite recent rains, there is still a pressing need for the plans in a region that has been hit by “its worst drought in recorded history,” said Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman.

“We didn’t get into this drought in one year, and we’re not going to get out of it in one year,” Burman told members of a Senate Energy and Natural Resources subcommittee.

The plan addresses water supplies in the river’s two biggest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, which Burman said dropped in 2018 to 40 percent of their combined capacity. She said the water level is the lowest since the 1960s, when Lake Powell was still filling.

Under previous agreements, states in the lower basin – Arizona, Nevada and California – began to lose their rights to the amount of water they could take from the river once Lake Mead fell below a certain level.

The new plan raises that threshold and eases the amount of water states have to give up initially – triggering an earlier but less harsh response in hopes of staving off severe shortfalls.

For Arizona, that means the state would have to give up – or “contribute” in the terms of the agreement – 192,000 acre-feet a year once Lake Mead levels fell below 1,090 feet, compared to the old contribution of 320,000 acre-feet after the lake fell below 1,075 feet. An acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover an acre of land to a depth of one foot, or 325,853 gallons.

It’s taken years of negotiating to reach the deal, which involves seven states, local and tribal governments, and the U.S and -Mexican administrations.

But for California and Arizona, much of the wrangling has been over how much different groups within their states would have to give up to make up the overall state’s contribution in a shortfall.

-Cronkite News video by Alyssa Klink

Buschatzke said that despite a lot of debate at the beginning of the process, Arizona was able to develop a plan that spreads the impact of contributions throughout the state after “folks came to the table” to work on a deal.

“They came to the floor and put resources on the table and essentially, they compromised, they made hard decisions that are difficult to get to,” Buschatzke said after the Senate hearing. “I think people felt comfortable that the deal as a whole worked for them.”

Representatives from the seven basin states wrote Congress on March 19 to ask for legislation allowing the states to enact their plans. That letter asked to have a bill signed into law by April 22.

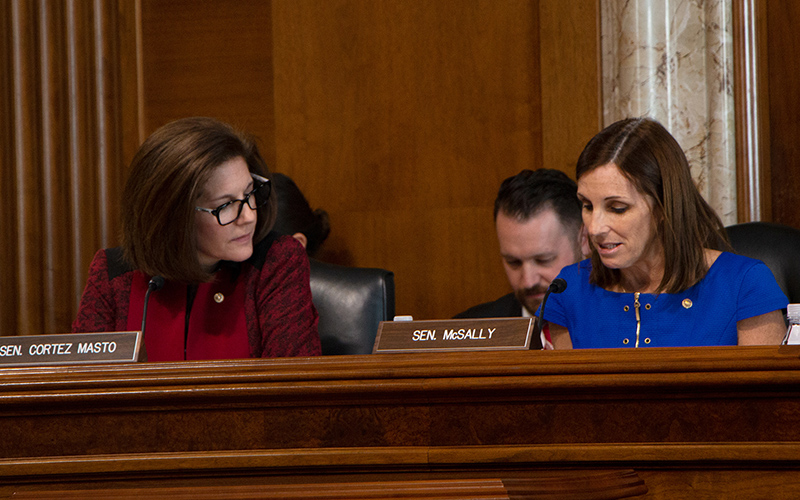

“Now that the states have completed their work, it’s time for Congress to take it across the finish line,” said Sen. Martha McSally, R-Arizona, at Wednesday’s hearing. McSally, who chairs the Water and Power Subcommittee, said she plans introduce enabling legislation “very soon.”

Buschatzke said in his prepared testimony that he hopes for quick action, because any delay “greatly reduces the sustainability of the Colorado River system.”

If the plan does not take effect, he said, there could be a “crisis” for the river, which provides water for more than 40 million people, irrigates 5.5 million acres of farmland and generates hydropower for millions.

Federal legislation “could avert such a crisis, and the time to act is now,” Buschatzke said in his testimony. He said the states have “developed a sound plan” for protecting the water supply while it also “protects and respects” water rights for those who rely on the river.

“Without this federal law, we would not be able to agree that anyone, including anyone in Arizona, could take their water out of the lake in a shortage condition,” he said.

Buschatzke and Burman are scheduled to be back on Capitol Hill Thursday to present the Drought Contingency Plan to the House Natural Resources Committee.

Even if the plan is approved, negotiators won’t get much rest, as the deal is only set to run through 2026.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.