National Park Service biologist Justin Brown discusses proper poop dissection with a volunteer during a scat party. Brown says LA will never be coyote-free. “It’s going to occur. They’ve already adapted.” (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

Urban coyotes easily co-exist with humans in Southern California. Authorities fear the animals will come to see humans as a food provider and “end up getting a little too pushy and end up biting somebody.” (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

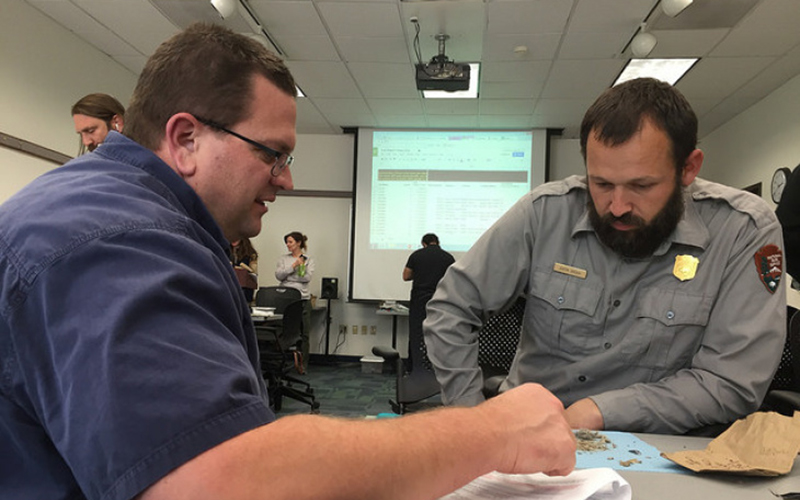

Cal State Northridge graduate student Rachel Larson talks with NPS biologist Justin Brown during a coyote scat party. Larson runs isotope scans to reveal how much human food coyotes eat. It’s a lot. (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

LOS ANGELES – First off, yes, this is a story about poop, which we all know is funny.

So please get all the snickers, chuckles and chortles out of your system now, because this poop story has a valuable lesson about how Los Angeles residents share this wildland-urban interface with coyotes – and why it’s our fault when things go wrong.

When it comes to Angelenos’ coyote troubles, Justin Brown, a biologist with the National Park Service, said he’s heard it all.

“I have people coming in telling me that their neighbor’s feeding them, some where the coyote’s coming up behind them, chasing them and their little dog as they’re walking down the street, to some people where there’s just a coyote that sleeps in their yard every day,” he told LAist. “If you’re having conflicts in your area, they’re coming into your neighborhood for a reason. There’s some sort of resource they’re finding.”

And Brown, fellow scientists and local nature fans investigated those reasons by looking at coyote scat.

For a little more than two years, NPS researchers and volunteers collected scat at 27 sites, most of them in LA, including spots coyotes frequent in Griffith Park, Boyle Heights, Eagle Rock, Frogtown, Beverly Hills, Culver City and Baldwin Hills.

In all, the research team collected and dissected more than 3,200 samples, which literally is a crapload.

A few of the sample sites were in more suburban and wildland pockets in the Conejo Valley, including Thousand Oaks, “to see if the amount and types of food vary based on a certain level of urbanization,” Brown said.

Despite having coexisted with them in Southern California for so long, much about urban coyotes remains a mystery, Brown said, such as pack size or even how many live in the city.

Investigating their diet is just one part of a larger NPS coyote study from the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, dubbed the L.A. Urban Coyote Project. The overall goal is to better understand how they’ve managed to carve out such a comfortable spot in the hybrid ecosystem we share.

How do you study scat?

It’s not as simple as finding droppings and grabbing a pair of gloves. Every coyote scat sample gets put through a process that basically eliminates the poopiest parts of the poop, Brown said. First the scat is brought to NPS scientists, who bake it for sterilization. The sample then is placed in a little nylon bag and gets washed and dried.

Fur and whiskers also offer clues about urban coyotes. (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

“You wash it to get rid of all that extra stuff, that way when you go to dissect it, you don’t just have lots of dirt,” Brown said.

After that, the poop is ready for inspection – and it’s time to throw a party.

NPS has hosted volunteer events where members of the public learn to dissect and catalog what they find in the coyote poop samples, aptly called scat parties.

Volunteer Merri Huang first heard about the project and the call for volunteers in a KPCC story and signed up. She said she has been a “a backyard naturalist” since moving to LA in 1980 (it probably helps that she has a master’s degree in field biology).

“(I) was amazed at the number of species in my own backyard,” she said, “and front yard, where I’ve seen coyotes off and on for years.”

At a typical scat party, Huang said, you check in, get coffee and a bagel, then grab a sample and get to work. Volunteers place their samples on paper towels and start picking out the contents into separate piles: animal parts, plants, fruits, insects and trash. Some volunteers don’t even bother wearing gloves, NPS spokeswoman Ana Beatriz Cholo said, adding that ‘gloves are kind of annoying,” and fur can stick to them.

Volunteers verify or correct their findings using matching samples, field guides and the internet, but also get help from Brown and other scientists.

“People are curious. They want to know what these animals are doing there,” Brown said. “This is the way they can answer some of those questions by coming and seeing.”

NPS scientists even had to turn down some poop eager volunteers wanted to bring in from backyards and other places, since they needed to focus on specific sites for consistent data-gathering.

“My favorite part was sharing science with others who were curious, perpetual learners, collaborating towards a future goal,” Huang said. “It’s fun to be with people who share my excitement about identifying a Dixie cup, or a rabbit’s tooth, or a reptile scale, a beetle’s wing, or even a microchip in a scat.”

After a bit of work, lunch is provided, then it’s back to more poop.

Volunteers are responsible for the vast majority of collections and dissections, Brown said, and he credited them for their hard, important work.

Unraveling the mysteries of feces

For Brown, who has been studying coyotes for nearly 20 years, what really stood out was how much fruit local coyotes eat. Most of it isn’t fruit humans throw out – the source is non-native, ornamental plants ubiquitous across LA. Some of the fruits commonly found in coyote scat included purple figs from ficus trees, pyracantha berries and dates from our iconic (but non-native) palm trees.

“Most people don’t even realize they eat fruit,” Brown said. “The coyotes definitely take advantage of them.”

Urban coyotes are also eating a lot of human and pet food, which was found in more a quarter of the samples. Other common meals are rabbits, cats, insects and gophers.

Brown believes most of the cat remains found in urban coyote scat point to feral cat colonies in those areas, which typically means someone in a neighborhood is feeding those feral cats. Of course, coyotes do sometimes get to small dogs, house cats and other pets.

Preliminary data from the study showed a notable difference between the diets of urban coyotes and those in the Conejo Valley. Most of those more suburban/rural coyotes munch on rabbits, fruit, rodents and insects, generally consuming far less human-generated garbage.

Brown noted that resources aren’t dwindling in the more wild areas where coyotes live, though “we’ve definitely pushed more and more into their habitat.”

Coyotes are just expert life hackers.

“They’re very good opportunists. They take advantage of resources that are available,” he said, adding that coyotes also are good at making pups.

“Generally, if there’s more food, there’s going to be more coyotes,” he said. “If the landscape can support them, they’re going to be there.”

But coyotes don’t stick to just the food pyramid, as scat inspectors found over the course of the study. Some of the more bizarre items found in their poop were baseball leather, stuffed-animal parts, a finger puppet, bits of broken glass, a condom and, ironically, a dog-poop bag.

Whiskers tell us even more

A coyote’s poop alone doesn’t give the full scope of their diet. A lot of easily digestible materials, including meat and dairy products, gets absorbed in the magical process of digestion. But there are other ways to see what coyotes are eating.

That’s where Cal State Northridge graduate student Rachel Larson lends her expertise. She has a bachelor of science degree in zoology, is pursuing a master’s in biology and is one of the lead volunteers on the NPS urban coyote project, focusing on diet study.

Some coyotes have a penchant for fast food, but they also eat a lot of fruit from such non-native plants as ficus and date palms. (Photo courtesy of Merri Huang)

“A delicious Egg Sausage McMuffin isn’t easy to recognize in poop,” Larson said. “However, in the United States, most of the food we consume has corn in it in some way.”

That corn contains noticeably higher amounts of carbon-13, an isotope that weighs more than a typical carbon atom. So when a coyote eats food with lots of corn or its by-products in it, that carbon-13 gets absorbed into their bodies, including their whiskers.

Larson runs collected coyote whiskers through a mass spectrometer, which allows her to detect the amount of that isotope, showing her how much human food coyotes are eating. And often, it’s a lot.

“What was surprising was how much urban coyotes relied on human garbage … it constituted 80 percent of their diet!” she said. “We would be missing a significant amount of human food if we just used scat analysis alone.”

What can be done

So, LA’s most urban coyotes are getting a majority of their food from garbage left by humans. And if they’re not eating our trash, many are eating fruit that falls from trees and plants that humans introduced to the region.

“We provide a huge amount of their food to them,” Brown said. “We need to realize that we are responsible for them being in our neighborhoods and we need to be dealing with that situation if we don’t want them there.”

And now that researchers have a good sense of what coyotes are eating, Brown hopes local residents can be educated and empowered to reduce the unnatural resources the animals take advantage of.

For starters, Angelenos can remove food sources, which could mean getting rid of ornamental fruit-bearing trees or “being very adamant about making sure there’s no fruit hitting the ground,” he said. That also means securing and reducing garbage, keeping streets free of litter and not leaving pet food – or pets – outside.

But “the worst kind of feeding” that happens is when humans intentionally feed coyotes, Brown said. He has seen people “giving resources we shouldn’t be providing,” by leaving pet food bowls out for wildlife, throw leftover food to coyotes in parks – even tossing burgers to them. That near-hand-feeding behavior is dangerous for coyotes, and potentially for people, too.

“The coyotes start getting to where they expect food directly from somebody,” he said, “so they come up to people and then they end up getting a little too pushy and end up biting somebody.”

Brown also recommended Angelenos look for ways to reduce cover by removing some vegetation and keeping yards free of debris, allowing coyotes fewer places to hide.

About 100 scat samples still need to be dissected, Brown said, which should be done in the next couple weeks. After that, he and his team will write up their findings and work to get them published in a scientific journal.

Their findings also will be used locally by the National Park Service to educate the public about coyote behavior and what steps can be taken to deter them from coming in neighborhoods.

But, as Brown noted, it’s impossible for every part of LA to be coyote-free.

“Coyotes are going to live amongst us,” he said. “It’s going to occur. They’ve already adapted and they can live quite well in our neighborhoods and in our urban environments.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Have a story idea? Email us at [email protected].