Protesters Andrea Castro (left), Janna Hynds and Karina Hawkins attended the Arizona Youth Climate Strike Friday. Several young advocates gave speeches at the event in support of climate change reform. (Photo by Oskar Agredano/Cronkite News)

Haven Coleman asks U.S. Representative Doug Lamborn (R-Colorado) to commit to renewable energy at a town hall meeting in 2017. (Photo by Jake Brownell/91.5 KRCC)

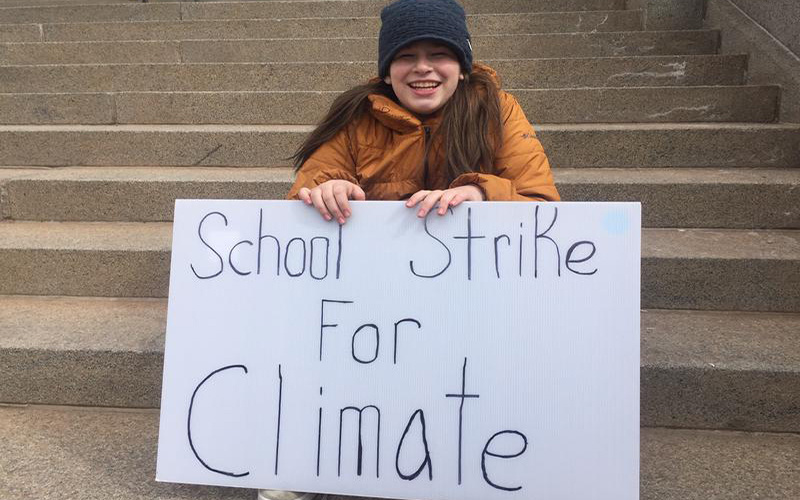

Denver-based 12-year-old Haven Coleman is one of three organizers for the U.S. Youth Climate Strike. (Photo by Ali Budner/Mountain West News Bureau)

Mishka Banuri is a Pakistani-American teen organizing the climate strikes in Utah. (Photo courtesy Mishka Banuri)

DENVER – Haven Coleman perched on the steps of the Colorado state Capitol in a puffy jacket and hat. The 12-year-old looked tiny against the gray stone columns rising up at her back. With her mom nearby, she held up a simple sign. On it, she had written the words “School Strike for Climate” in big black letters.

Coleman is one of the youngest organizers of US Youth Climate Strike by grade school students around the world that took place Friday, including in Arizona. Students are demanding political action on climate change.

Aditi Narayanan, a 16-year-old student who attends BASIS Phoenix Central charter school, helped organize the AZ Climate Strike at the state Capitol, which took place Friday afternoon.

“We all just noticed the effects of climate change on communities and on people rather than it being an abstract concept,” Narayanan said as she talked about the extreme heat in Phoenix and Arizona’s ongoing drought. “I do believe the existence of us as humans is definitely at stake here, and also, I believe that the livelihood of many people are at stake.”

Attendees at the Phoenix rally registered to vote, signed up to volunteer and learned more about environmental organizations, which had set up tables to spread awareness about climate change. “I do truly hope that we get the community sparked up, and they realize how climate change injustice affects them,” Narayanan said.

Narayanan wants to raise awareness about how people can use local government to help address the effects of climate change. “If people realize that they can hold their elected officials accountable, that will be another success,” Narayanan said.

She’s not alone.

Coleman has been speaking out on environmental issues for years. In 2017, a video of her went viral in which she questioned U.S. Congressman Doug Lamborn, a Republican, about his support of coal instead of renewable energy at a town hall meeting in Colorado Springs.

Coleman described the event.

“I was super persistent,” she said. “I crawled up to the front of the room, stared that man down and then when he was picking people I’d jump up and he was like three feet away from me and I’d just start jumping with both hands, like ahhh!!!”

She got his attention.

Sitting on the Capitol steps, Coleman didn’t actively approach people, but she did get thumbs up and waves from people passing by. Some stopped to take pictures of her with their smartphones. Others asked questions.

One passerby, Cory Hithon, who introduced herself as a home health care worker and an activist, seemed confused about the wording on Coleman’s sign. “School for climate?” she asked. “What is it? What are you doing it for?”

Coleman responded the way she has countless times, patiently breaking down the science of climate change to adults and explaining why it matters to her enough to leave school.

“The crisis that we’re dealing with right now, it’s destroying my future and our present,” Coleman said. “I guess I’m fighting to stop the worst effects.”

Hithon considered Coleman. “You know something? We lay down for a whole lot and stand up for not too much,” she said. “I’m glad that the younger generation is showing the older generation ‘get off your tushes and do something for somebody!’ So thank you. Continue to do what you do and I will look at that climate change.”

She gave Coleman a high five.

“That was fun!” Coleman said. “That’s the first interaction of the day, and it was a positive one. At least it wasn’t like somebody flipping me off like two weeks ago.”

Coleman has been at the capitol every Friday since the beginning of the year, even in the rain and snow. “I had to do it,” she said. “If you don’t do it every Friday then it’s like you just lost it. You’re just doing it once and it’s not really Friday striking.”

Coleman was inspired by the growing worldwide movement called Fridays for Future. Students strike from school once a week to raise awareness about climate change.

The movement was started by another teen activist: Greta Thunberg from Sweden. Thunberg has taken to regularly addressing the media and world leaders, including at the UN Climate Conference in Poland last year.

Speaking to delegates there, she said “I have learned you are never too small to make a difference. And if a few children can get headlines all over the world just by not going to school, then imagine what we could all do together if we really wanted to.”

Earlier this year, Thunberg took the momentum from her Fridays for Future movement to motivate tens of thousands of students across Europe to demonstrate en masse for climate.

Coleman thought to herself, “OK. I want to support her and do something here in the U.S.”

She decided to join up with two other teens – Isra Hirsi of Minnesota and Alexandria Villasenor of New York – to organize the US Youth Climate Strike. Together, they created a network that has spawned the planning of hundreds of student strikes across the country.

Tens of thousands of young people from at least 100 countries turned out Friday to support policies like the Green New Deal and weaning the U.S. economy off fossil fuels in favor of renewables.

Polls show young Americans are far more likely to believe climate change is happening and caused by humans.

The climate movement has drawn in scores of other kids who planned events in their own states, including Liam Neupert, the 16-year-old state leader for Idaho.

“I had called my mom and I was like so I’m gonna lead a climate strike on the 15th,” Neupert said. “And she’s like ‘what?'”

But like many other parents in this teen movement, she now supports him. Neupert said he was inspired by the student-led March for Our Lives movement that followed the Parkland school shooting last year.

He said the issues are related. Kids don’t feel safe in school and they feel like their world isn’t safe either.

“Like, if we don’t have an earth to live on, where are we going to go?” Neupert asked.

Amidst these existential questions, he struggles to find time for school work. He said he’s always responding to messages on email and Slack and text and making sure he’s posting on social media.

“It’s like juggling another life,” Neupert said.

And according to 16-year-old Boulder activist, Marlow Baines, it also means juggling lots of very different peers.

Some of her fellow youth organizers are pro-life but they’re also climate activists. “Others are pro guns,” she said, “and yet they are also climate activists, because they see this is an issue that we need to deal with.”

After attending the protests at the Standing Rock Indian reservation in 2016, Baines was fired up. She joined her local chapter of Earth Guardians, a worldwide organization that supports young environmental activists.

In 2015, Earth Guardians joined 21 young people in filing a lawsuit against the U.S. government for failing to act on climate change. The case is still unresolved.

But Baines is committed to environmental work. She left public school during her sophomore year.

“I came to my parents and said ‘I can’t do this. The system is not teaching me the right things,'” Baines explained. She turned to homeschooling and independent study to give her more time for climate organizing.

Baines said one of the most important things she’s learned is that the climate movement has to make room for marginalized voices if it’s going to succeed.

Mishka Banuri, an 18-year-old Muslim activist in Utah, agrees.

“I was so terrified joining this movement,” said Banuri, “because often times in planning meetings I looked around and I was the only young person and I was the only person of color in the room. That was really scary. And it gets scarier as you move through the legislature and you have to testify.”

Banuri won a Brower Youth Award last year for her role as one of the young people that helped get a climate resolution passed in Utah.

But, she said, in conservative-leaning Mountain West states like hers, the conversations about environmental issues can be more challenging than they are on the coasts.

“In Utah we are really at this basic level where we’re still trying to convince people that climate change exists,” Banuri said.

She said one way she tries to relate to politicians in Utah is through religion. She knows faith is important to many Latter Day Saints leaders in her state, and her own faith is at the root of her environmentalism. “As I read the Koran,” she said, “there are many verses that explain that it’s important to keep the earth healthy because the earth keeps you healthy.

But at the end of the day, Banuri said it’s hard to be taken seriously as a young person. That’s a reality that 12-year-old Haven Coleman can relate to.

“Everybody tells us like OK wait and like, grow up! And then you can be a scientist and figure out, like how to save the world,” Coleman explained. “I’m like well scientists already figured out how to save the world we’re just not acting on it and nobody listens to these scientists! Also, we don’t have that much time!”