WASHINGTON – Hopi Vice Chairman Clark Tenakhongva said he already sees a difference in the year since the Trump administration shrank the size of Bears Ears National Monument, excluding some culturally revered land.

“Today, there’s a lot of vandalism, there’s a lot of looting and that still continues,” Tenakhongva said. “So that is the fear that Hopi has because we have our spiritual ties to the kivas there in Bears Ears.”

Tenakhongva joined officials from the Pueblo of Zuni and the Ute Indian tribes before the House Natural Resources Committee on Wednesday to testify on their worries since President Donald Trump slashed the monument by 85 percent – from 1.35 million acres to about 200,000.

Tenakhongva said Bears Ears has “spiritual churches” to tribe members, but now when he visits he finds them littered with trash.

Critics of Trump’s December 2017 proclamation complained it was made without consulting local residents and officials.

But supporters of the reduction noted that Bears Ears was shrunk the same way it was created – unilaterally by a president.

Then-President Barack Obama designated the 1.35 million acres in southeastern Utah as Bears Ears National Monument in the waning days of his presidency using the century-old Antiquities Act. The 1906 law allows a president to single-handedly create monuments to protect important cultural, historic, environmental and archeological sites without input from local communities.

Past presidents have used the act to designate 157 monuments, according to the National Parks Conservation Association, but few on the scale of Obama.

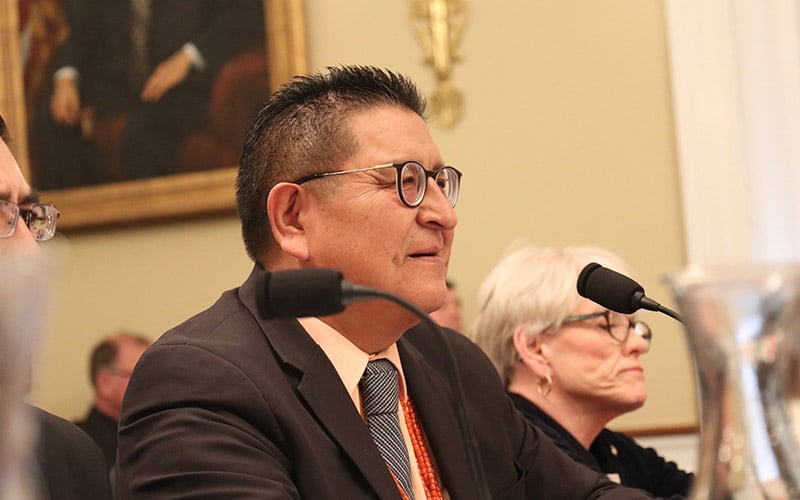

Hopi Vice Chairman Clark W. Tenakhongva told the House Natural Resources Committee that tribes should have been consulted before President Donald Trump decided to slash the size of Bears Ears National Monument. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News)

But the law says land designated under the act should be “confined to the smallest area compatible” with the protected items or areas. When Trump signed proclamations downsizing Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in December 2017, he said it was because the monuments far exceeded the limited protections allowed under act.

Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, a longtime critic of Bears Ears, said the process of designating such monuments is flawed from the start.

“The Antiquities Act … using that act only has one person who has any kind of voice in that process,” Bishop said Wednesday. “There is no allocation of input, there are no solutions to be done in advance.

“There are no rules, there is no process in the law for either creation or readjustments and that’s part of the problem,” Bishop said.

Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, questioned Trump’s rationalization for the reduction, pointing instead to what he calls the pro-energy bent of the administration and then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

“If you look at the culture of the Interior under Zinke and Trump, the interest is how do we help industry,” Grijalva said. “It’s about what we can take out of the land as opposed to what we can do to preserve it and conserve it. It’s two different philosophies.”

There was input on the creation of Bears Ears. The monument was the result of coordinated campaign by tribes in the region, who banded together as

the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Council to push for the monument.

The council originally sought protection of 1.9 million acres in southeast Utah, land they said was packed with cultural sites, including the Hopi tribe’s worship areas. The reduction to 1.35 million acres was acceptable, but Tenakhongva worries what will happen now.

“That is culturally our way of worship to the higher power,” he said. “It’s not even a quarter of what it should be, as far as protection goes.”

-Cronkite News video by Alyssa Klink