Researchers prepare to measure ironwood trees near El Desemboque, a Sea of Cortez fishing village in Sonora, Mexico. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

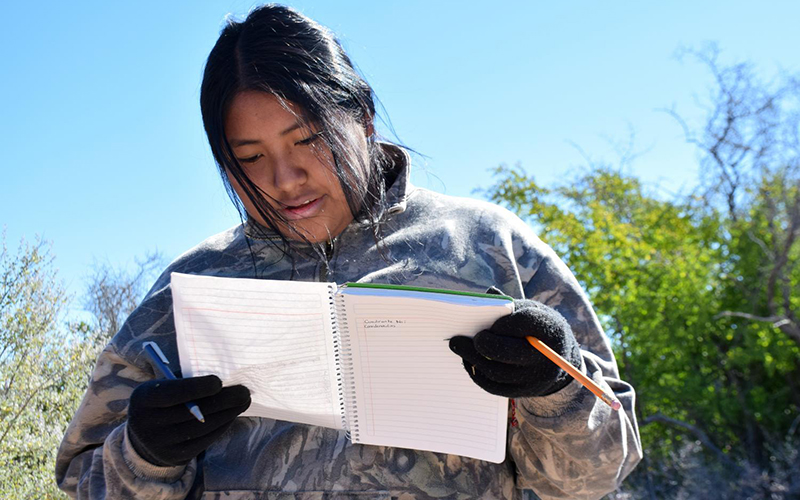

Student researcher Kenya Estrella reviews measurements during a habitat conservation study near the Sonoran village of El Desemboque. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

EL DESEMBOQUE, Mexico – There’s one thing that connects the more than 900 members of the binational group Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers.

“Immensely beautiful and mesmerizing,” said Benjamin Wilder, a University of Arizona botanist who directs the group, known as NGen.

“A special place,” agreed indigenous ecologist Mayra Estrella.

“It’s a treasure for humanity,” said social anthropologist and marine biologist Michelle Early.

“I know I want to stay here for my whole life,” added David Dearmore, a budding acoustic ecologist.

These researchers are bound by their passion for the expansive mountain ranges and vast open stretches of the Sonoran Desert, which covers most of the southern half of Arizona, a slice of southeastern California and much of northwestern Mexico and the Baja Peninsula.

Wilder said NGen was created almost nine years ago to bring together young researchers committed and passionate about studying this region – and to tackle such challenges as climate change, mega-development and a border wall in different ways.

“The approaches that we’ve taken to science, to conservation – we’re losing a lot of battles right now,” he said.

So NGen is trying new things, such as combining art and science and reaching across academic disciplines.

“And using that new, fresh perspective to shake things up,” Wilder said. “All of the challenges we face right now require new ways of thinking.”

One example: a pair of habitat conservation projects in a small indigenous village of the Comcáac people, also called the Seris, on the northwestern coast of Mexico’s Sea of Cortez.

‘It’s really sacred to me’

On a recent Saturday, researchers packed their cars in the fishing village of El Desemboque, then took off down narrow dirt roads, leaving behind the sea and the flat-roofed stucco houses as they bumped and rattled into the desert wilderness of the nearby mountains.

Ecologist Mayra Estrella, who is Comcáac, is leading a study about the health of ironwood, mesquite and mangrove trees. Because these trees, especially the ironwood, are sacred, she said.

“It’s really sacred to me, and for the community,” she said. “It a story, a history.”

The Comcáac use ironwood in traditional medicine, for shade, firewood and intricate carvings.

As Estrella and her team measured the trees and documented the diversity of species in that area, David Dearmore, an acoustic ecologist in training, tucked small microphones into the crevices of trees to record them creaking and swaying in the wind. Then he arranged them on a cactus, showing two Comcáac students how to pluck the thorns to make different sounds.

The NGen researchers are looking into the health of ironwood, mesquite and mangrove trees near El Desemboque. The Comcáac people consider trees, particularly ironwood, to be sacred. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

Dearmore also is recording Comcáac traditional songs. Nested beneath the branches of a large ironwood to escape the wind, he knelt in front of Estrella, who sang a song to a mesquite tree.

Later he arranged the mics to record tribal elder Manuel Montoy, a tall, lanky man in slightly mismatched camouflage clothes. As he sang an ancestral song about the connection between humans and nature, the creases around his eyes deepened as he smiled.

More seats at the table

But Dearmore, who’s 20 and not in college, said it’s hard to get financial support for his work.

“You don’t see a lot of groups that are specifically focused on helping young people out without some sort of attachment to college,” he said.

NGen had no such reservations. It awarded him a grant for his acoustic ecology project in El Desemboque.

Michelle Early, NGen associate director, said the grants are “for projects that are interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, innovative, and that maybe wouldn’t be able to be funded through traditional outlets.”

NGen wants to give people from different backgrounds an equal place at the table, she said, a network of shared knowledge and perspectives that gives NGen its strength.

Wilder, NGen’s director, said the group’s fiscal sponsor is the International Community Foundation, a Southern California nonprofit that works with underserved communities in Baja California, Mexico. NGen’s board and executive branch are run entirely by volunteers, with chapters on both sides of the border, he added.

“It’s allowed us to grow well thus far,” said Wilder, who also directs the UA’s Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill, which was established by the Carnegie Institution in 1903 to study how plants adapt to aridity.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Follow us on Instagram.