Capt. Alivia Stehlik, Capt. Jennifer Peace and Staff Sgt. Patricia King (from left) wait to testify before the House Armed Services Committee on the effects of the administration’s proposed ban on transgender service members – a ban they say will backfire. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News)

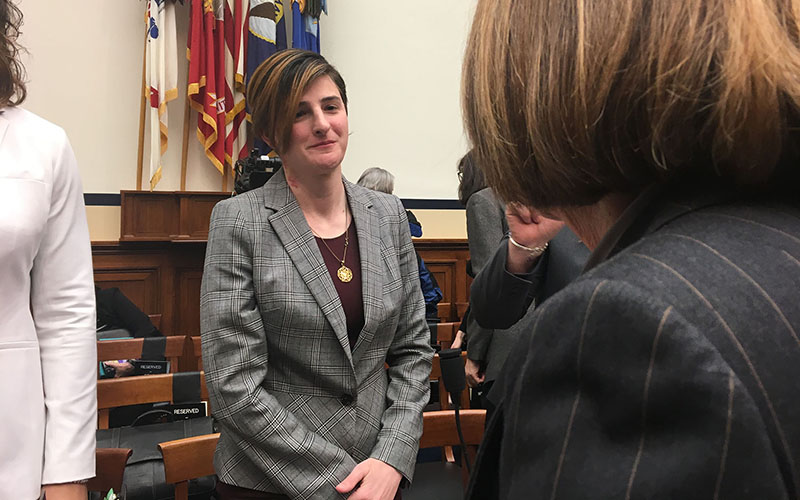

Capt. Jennifer Peace, who was stationed for a time at Fort Huachuca, served in the Army when an earlier ban on transgender soldiers was in effect. She says her quality of life vastly improved when that ban was lifted in 2016. (Photo by Keerthi Vedantam/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Capt. Jennifer Peace loved the time she spent stationed at Fort Huachuca with her family, even though she was living in fear.

“There was always that discomfort that someone might find out that I was trans,” Peace said recently. “I loved Sierra Vista and Bisbee and being there, but I was just more stressed.”

All that changed when the Pentagon in 2016 lifted its ban on transgender military service, which was “like night and day” for Peace. She began to wear her hair longer, use women’s restrooms and wear a different uniform. Her subordinates, who already knew her as a woman, were finally allowed to call her “ma’am” instead of “sir.”

After serving in the Army for more than a decade, with tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, the change in policy “was one less thing for me to worry about,” Peace said. “I was much better at my job after transitioning because I was able to integrate with my troops better.”

That’s why Peace told a House committee recently that a Trump administration decision to reimpose the ban would be dangerous.

She was one of five transgender, active-duty soldiers who testified last week as the House Armed Services Committee held the first congressional hearing on the issue since President Donald Trump ordered a ban on transgender military service in 2017.

The witnesses – testifying in civilian clothes after the Pentagon said they could not appear in uniform – said the ban would have the opposite effect from Trump’s claim that it would improve military readiness.

“It is a national security issue and defense issue to reduce the pool of qualified candidates to pull from,” Peace said of the ban in her testimony.

But Pentagon officials defended the policy, saying it is aimed at the diagnosis of gender dysphoria, not transgender personnel. It is much like how the military screens service members with diagnoses of scoliosis or other medical conditions that could have an impact on readiness.

“The only difference between the (20)16 and ’18 policies is that the new policy ends the practice of providing special accommodations to individuals with a history or diagnosis of gender dysphoria,” said James N. Stewart, acting Defense undersecretary for personnel and readiness.

Sitting in uniform at the hearing, Navy Vice Adm. Raquel C. Bono said a diagnosis of gender dysphoria would not necessarily be disqualifying to military service: A service member could get a waiver to serve, as they could for other medical diagnoses. But she said the Pentagon wants to screen for gender dysphoria because of how anxiety and depression would affect readiness.

“We see it as an association with this diagnosis,” said Bono, director of the Defense Health Agency. “We see a higher rate in suicidal ideation.”

The change was announced in a tweet by Trump, but it was not until a year later that then-Defense Secretary James Mattis unveiled the policy after consulting with a panel of medical and military experts he convened.

The Mattis policy would grandfather in service members who are currently serving and who have received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. But transgender individuals would not be able to enlist and active troops who are diagnosed after the policy takes effect would no longer be able to serve.

The Palm Center estimates that only 6 percent of active-duty transgender service members have been diagnosed, leaving close to 14,000 soldiers and sailors in danger of being kicked out under the Mattis plan.

The plan was immediately challenged in court and blocked before it could take effect.

But the Supreme Court in January, without ruling on the ban itself, lifted injunctions by two lower courts. The only thing keeping the ban from taking effect at the moment is an injunction issued by another court that the Supreme Court has not yet considered.

Brynn Tannehill, a veteran who was in the audience for the committee hearing, knows what transgender soldiers will face if the Mattis policy does go into effect.

Tannehill, who grew up near Luke Air Force Base and dreamed of being a pilot, left the Navy so she could get treatment after years of struggling with gender dysphoria while on active duty.

“These people are out there doing the job that they’re trained to do, that they’re capable of doing it,” she said. “Transgender people can and do serve with honor and distinction.”

Tannehill has been trying for years to get back in to the military, but worries that another ban on transgender service will disqualify her.

Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix, said such disqualifications would be a loss to the military.

“We should not be banning anybody from our military that has leader qualifications, that is deployable and that will continue to make this military the most lethal military in the world,” said Gallego, a Marine veteran and member of the Armed Services Committee.