-Video by Gabrielle Olivera/Cronkite News

GRAND CANYON VILLAGE – It’s a cold winter night along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, and as she shuffles through the fresh snow, Abbie Smith can’t think of a better place to celebrate New Year’s Eve.

As midnight strikes, the Mesa resident is overjoyed to be staying in the park that has reached its centennial year.

She and her friend of six years, Anne Kenison of Gilbert, are just two of more than 6 million people from around the world who enjoy the canyon’s natural splendors each year.

Both of them recognize that while visiting Grand Canyon allows them a place to escape, all visitors share a responsibility to preserve the park, which faces challenges in how to manage all those people while protecting the park for future generations.

Smith and Kenison, who bonded over their love for national parks and Arizona, used the park’s 100th anniversary to launch a yearlong quest to try 100 new things at the park. So far, they’ve hiked into the canyon, eaten dinner at the Grand Canyon Lodge and braved the cold to take in the view at Yaki Point.

At each checkpoint, the women write the accomplishment on a whiteboard, snap a selfie and move on to the next adventure.

The journey of a lifetime

Smith’s love of national parks began at a young age.

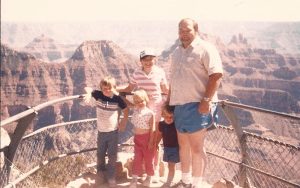

“I grew up going to national parks as family vacations,” Smith said. “I have a love for natural places and national parks. I have a picture of me at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon when I was really little.”

Abbie Smith, second from the left in the front row, visited Grand Canyon National park when she was four years old with her family. “I have a love for natural places and national parks,” said Smith. (Courtesy of Abbie Smith)

But it wasn’t until Smith and Kenison went to hear photographer Pete McBride and writer Kevin Fedarko, who traveled more than 750 miles within the Grand Canyon to raise awareness about sustainability, speak at a National Geographic live event that they decided to get to know the canyon better.

“I know it’s four hours away, but it’s still my backyard,” Smith said.

The project is more than just checking off things to do, she said.

“It centers me,” Smith said. “It grounds me. It makes me reflect on my life. … I’m disconnected from things that don’t matter and connected to the things that do. It’s easy to just turn things off and just tune into other senses and the canyon itself. It is an amazing place. It’s unfathomable.”

The canyon’s popularity with visitors has led to an increase in traffic over the past few decades, she said, making the push for sustainable efforts at the park more urgent.

“I think protecting the resources at the park allows our future generations to also have spaces where they can disconnect from computers, from screens and the pressures of everyday life in a beautiful place that makes them feel grounded,” Smith said.

McBride, who is passionate about park preservation, hiked the entire length of the Grand Canyon in one year to raise awareness for the challenges facing this natural treasure, which President Theodore Roosevelt called “absolutely unparalleled throughout the rest of the world.”

“It’s not a bucket-list item that we check off for luxury and convenience,” McBride said. “It’s a place that requires you to get away from your vehicle, embrace its silence, appreciate its night sky, be aware of its remarkable biodiversity, and not its geological history but also its archeological history.”

He said threats to the park include a proposal to build a tourist gondola across the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers, ongoing uranium mining and a huge expansion of helicopter tourism at the park. There are nearly 120,000 commercial flights every year, according to 2016 data from the park.

“If it continues the way it is, we’re not going to leave the park the way it is,” McBride said. “It would set aside what has been called ‘America’s best idea’ to create these national parks and leave them for the next generation. It would be sad to change it in the name of making a profit for a small number of people.

Although Native American tribes who live in the canyon deserve economic opportunities, he said, they often do not profit from expansions at the Grand Canyon.

“People just assume it’s a protected landscape, and I believe it requires each generation to step up and voice how they feel about it,” McBride said.

100 years of exploration

Humans have lived in and around the Grand Canyon for thousands of years, but efforts to reserve it for the public are relatively recent.

“It was a national forest and then a national monument and then a national park in 1919,” said Paul Sutter, environmental history professor and the author of Driven Wild: How the Fight Against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement, which tackles the dilemma of national parks protecting the landscape while accommodating increased tourism.

Once Americans embraced the automobile, he said, the National Park Service was able to attract large numbers of tourists.

“There was a shift in tourism from 1901 to years after World War I when a large number of automobiles started arriving, and it really changed the nature and patterns of visitation,” Sutter said. “The infrastructure of the automobile travel began to catch up around World War I.”

The National Park Service began a See America First campaign during World War I to entice people to drive out West, Sutter said.

“When most Americans thought about tourist travel, their first impulse was to go to Europe and go on a grand tour of all the famous sites,” Sutter said. “When that possibility got shut down around World War I, the See America First campaign was to increase tourism but also to create American identity through spectacular landmarks.”

-Video by Jonah Hrkal/Cronkite News

Places like the Grand Canyon are what make the U.S. stand out, he said.

“Europe may have these ancient ruins and all this history, but we have these monuments to nature, and that’s what made America a distinctive place.”

As a historian, Sutter knows every national park struggles to protect natural resources and manage visitation.

The Grand Canyon had nearly 38,000 visitors during its first year as a national park in 1919.

Today, the park welcomes more than 6 million annually.

“I personally wish we could figure out a way as a society that could better socialize the costs across the entirety of the population rather than raising the prices so much that you begin to put the experience out of reach for some people,” Sutter said. “I also know this is where they get their money and parks are in desperate need of money.

The Grand Canyon is the second most visited national park after Great Smoky Mountains National Park, according to the National Park Service, and it’s suffering from wear and tear. The park has a maintenance backlog of over $300 million.

Preserving the park

Roosevelt declared the area a national monument in 1908, but several bills to have it declared a national park failed to pass Congress.

“In the Grand Canyon, Arizona has a natural wonder which is in kind absolutely unparalleled throughout the rest of the world,” Roosevelt said. “I want to ask you to keep this great wonder of nature as it now is. Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.”

Roosevelt, however, was out of office by the time Congress approved the Grand Canyon National Park Act. It was signed Feb. 26, 1919, by President Woodrow Wilson.

As the canyon celebrates its 100th anniversary, 2019 will be a year to honor the national park through a push for sustainability, according to centennial coordinator Vanessa Ceja.

“This is a place that’s going to stay here for thousands of years and we want it to stay for future generations,” Ceja said.

Over the next two years, the park will make the switch to zero landfill. Over the past five years, the National Park Service has put solar panels on staff housing and enforced single-stream recycling, Ceja said.

“We have one dumpster where all of our trash gets taken to so that’s increased the amount of recycling we’ve done in the park,” Ceja said. “By having less dumpsters, we’re reducing carbon emissions from trucks.”

Staff members will continue to encourage sustainable efforts, she said, but there are changes visitors can make to help preserve the canyon.

Visitors should take all their trash with them when they leave; leave all rocks and fossils; not vandalize the canyon; stay a safe distance from wildlife; and if you need to use the restroom in the inner canyon, dispose of your waste properly.

“Even though you are just a visitor, your actions here in the park have an impact,” Ceja said. “You don’t have to be a park staff to be a steward.”

Like any national park, anyone who visits has a responsibility to preserve the parks for generations to come.

“They are just places you really hope everyone can get to at one point,” Sutter said.

For Smith and Kenison, they know that a place so grand deserves multiple visits. They are continuing their quest to complete 100 adventures in and around Grand Canyon this year.

Smith and Kenison just completed over 80 tasks and their final, culminating experience will be rafting the Colorado River in June.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Follow us on Instagram.