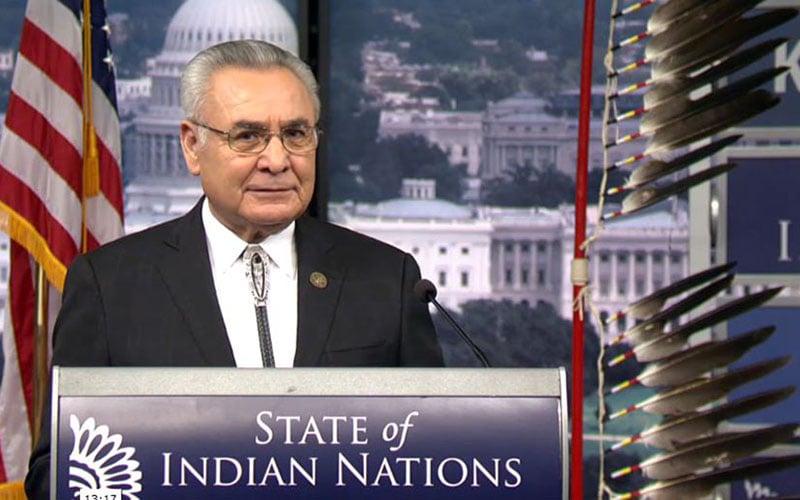

National Congress of American Indians President Jefferson Keel said the state of Indian nations is strong, but that they were hit hard by the government shutdown and should not have to suffer through another. (Photo courtesy the National Congress of American Indians)

WASHINGTON – Tribal leaders Monday called on federal lawmakers to avoid another government shutdown, saying the shutdown that ended in January was felt across Indian Country, hitting everything from housing to tribes’ efforts at economic development.

“The shutdown cut particularly deep across Indian Country, disrupting access to vital services like healthcare, housing, and food distribution, and endangering public safety, from unplowed, snow-covered roads to unsupported children at high risk,” said Jefferson Keel, president of the National Congress of American Indians.

Keel’s comments during the annual State of Indian Nations address comes days before the deadline for Congress to reach agreement on a budget deal or face another government shutdown, just three weeks after the end of that longest shutdown in history.

That shutdown began in December when President Donald Trump refused to sign a budget bill for about a quarter of the government because it did not include $5.7 billion for his border wall.

It ended on Jan. 25 when a three-week budget was approved to give lawmakers time to negotiate a border security plan as part of a longer-term budget. But the extension only runs through midnight Friday and Democrats and Republicans on the conference committee are reportedly at an impasse over funding for holding space for immigrants charged witth entering the country illegally.

“The shutdown is a sobering reminder of the failed state of our partisan politics,” Keel said. “America can no longer afford a government fixated on settling political scores and pandering to corporate interest. Indian Country certainly can’t.”

The shutdown hit hard on the Navajo Nation, where roughly 5,000 Navajo saw federal aid put on hold and road maintenance stalled in the midst of a snowstorm, denying some tribal members access to water and heat.

“The cost for that is pretty high due to a lot of constituents living out in the rural area,” Navajo President Nez said Monday.

As a result of those delays, Nez said the Navajo government is prioritizing infrastructure for water lines, electricity, roads and telecommunications in the upcoming year. He also said the tribe has “made it a priority for the Navajo people to advocate on new infrastructure at state capitals.”

Infrastructure can boost everything from plans for manufacturing facilities, which could help with chronically high unemployment on tribal areas, to broadband Internet service that could improve mental health care through telemedicine.

“We’d like for rural communities to not have to go to the large cities of our nation to get a checkup or to get health care services,” Nez said. “And we are not able to do that because we just don’t have that infrastructure on the Navajo Nation.”

While he defended tribal sovereignty, Keel said the federal government needs to live up to its obligations to Indian Country, saying the “mortgage payment is due” on the lands the government holds in trust.

Others at the speech said it’s hard to separate tribal life from the federal government.

-Cronkite News video by Micah Bledsoe

Maria Keteri Pablo, 18, winner of the Miss Tohono O’odham title, grew up in a ranching family in San Miguel, near the border. She said the family’s cattle sometimes stray over the Mexican border – even though the animals are still on Tohono O’odham tribal land.

“Cattle is very important to us,” said Pablo, a student at the University of Arizona. “It’s always been a part of our nation and it’s always been a part of our lifestyle and it’s a means for survival.

“Not being able to get it back is a challenge for us,” she said. “It brings money, it brings food.”

Edawnis Spears, a Navajo woman on her mother’s side who grew up in Arizona, said there are “so many instances where our identity and our culture and our family intersect with a federal government … like getting this card.”

The card she referred to is the certificate of degree of Indian blood she is seeking from the Bureau of Indian Affairs for each of the four children in her multitribal family – her husband is a council member of the Narragansett tribe.

“When you have something that’s foundationally intersectional that way … it’s important to see what direction the federal government is going to go to next so we know how to better equip our families with important information,” Spears said.

The relationship with the federal government is not always a good one, said Spears, who works to give her children a sense of their culture.

“You want to instill these in your children because you never know if someone else will take them away,” she said. “So much of what we experience as Indian people is tied to how much the federal government allows us.”

Despite what he called a “broken” federal government, Keel said the overall state of Native nations is strong. He pointed to united tribal actions on climate change and efforts to stop changes to the Indian Child Welfare Act and strengthen the Violence Against Women Act.

He also pointed to greater acceptance of Native Americans. Voters in New Mexico and Kansas elected the first two indigenous women to Congress this year, part of a wave of Native Americans who won statewide and federal offices, and to growing prohibitions by sports leagues on the use of Indian mascots.

Keel attributed those gains to continuing growth “in tribal sovereignty and self-determination.” Nez agreed that those are key.

“I mean, wouldn’t you say sovereignty is the ability to take care of yourself?” Nez asked. “That’s what we’re focusing on.”