PHOENIX – Protesters have raised renewed concerns about proper care for dolphins in a captive environment in light of the recent deaths at Dolphinaris Arizona, which has temporarily shut down after the death of a fourth dolphin, Kai.

The 22-year-old bottlenose dolphin was euthanized last month after showing difficulty eating, breathing and swimming, according to the Associated Press. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said officials are aware of Kai’s death and are “working on the next course of action,” according to a previous KJZZ article.

Dolphinaris officials said they were heartbroken by the deaths and are consulting outside veterinarians, pathologists, water-quality experts and animal-behavior specialists.

“We recognize losing four dolphins over the last year and a half is abnormal,” general manager Christian Schaeffer said in a statement. “We will be taking proactive measures to increase our collaborative efforts to further ensure our dolphins’ wellbeing and high quality of life.”

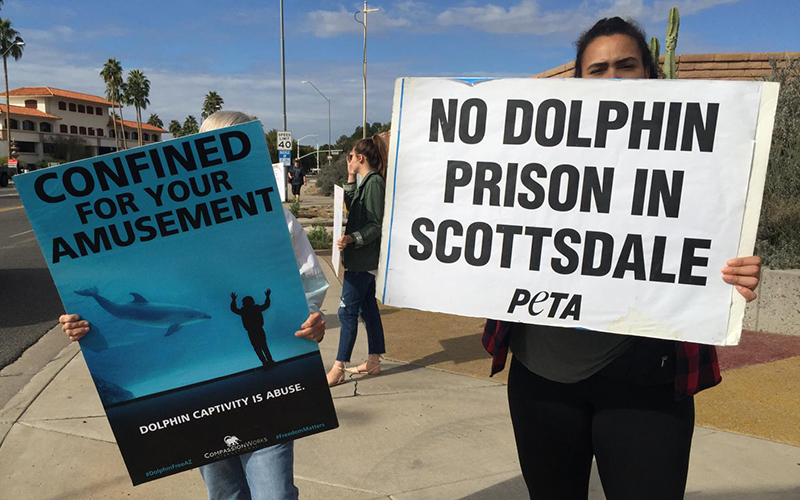

Since 2017, dolphins Bodie, Alia, Khloe, and Kai have died at Dolphinaris Arizona, which has been the target of protesters since it opened on tribal land east of Scottsdale in 2016. After Kai’s death, however, protesters gathered outside the facility have demanded the remaining dolphins be freed. Two of the four remaining dolphins have been returned to Dolphin Quest, which loaned them to Dolphinaris, according to KNXV (Channel 15).

KJZZ host Lauren Gilger spoke with Danielle Riley, who organized a protest of Dolphinaris and chairs activist group Plea for the Sea. She also interviewed Linda Erb, an instructor at the Dolphin Research Center in the Florida Keys.

LAUREN GILGER: We begin with news about Dolphinaris Arizona. It will close starting this weekend for an unspecified amount of time. The facility is bringing in outside experts to investigate why four dolphins have died there since 2017. Protesters like Danielle Riley say they want to see the attraction closed permanently.

DANIELLE RILEY: These are highly intelligent mammals that suffer dramatic costs in order to be in captivity.

GILGER: They’ll make those demands outside the building again this Saturday. PETA has also gotten involved, saying Dolphinaris should never have been built in the first place. These dolphin deaths have sparked new debate here over whether dolphins should live in captivity at all. So we wanted to get the perspective of someone who is very familiar with dolphin care and well-being.

LINDA ERB: At Dolphin Research Center, our dolphins do live in the Gulf of Mexico. So it’s a beautiful natural habitat, natural lagoons, bay-bottom mangroves surrounding the lagoons.

GILGER: Linda Erb is vice president for animal care and training at the Dolphin Research Center in Florida. She spends her work days on a tiny island in the Florida Keys, where off the coast, 26 dolphins live in an acre of enclosed water. Erb has watched many of those dolphins grow up in her 40 years working there, and I asked her what’s most important when caring for them.

ERB: You need to make sure that their environment is right for them, that it’s a positive environment. As far as the habitat itself, the social groups – having them live in the right social group lessens stress. Anytime you’re living with somebody you really don’t like living with, it can cause stress, whether you’re a human or dolphin. So having them in the right social group is really critical. Having the right team of people caring for them is huge. The trainers are the first line of defense for the dolphins. They know them like they know their own kids. We’ve watched these dolphins grow up. We know them. So knowing their behavior when it changes very slightly is sometimes the first warning you get that there might be a health concern.

GILGER: So the reasons for the four dolphins who have died at Dolphinaris here in the Valley vary from like a parasite in one to a bacterial infection in another. I know you don’t know the specifics of these cases and don’t need to talk about that, but can you tell us, generally – are dolphins as a breed at risk for any particular illnesses or infections, and what do caretakers need to do to kind of watch out for those things?

ERB: Well, dolphins as a species are very well-equipped for living where they live in the ocean. There are some things that we’ve learned over the years that they can be more susceptible to that you need to watch out for. For example, our nose has little hairs in it. And when we breathe, it filters what’s going into our lungs. Dolphins’ blowholes don’t have that. So when dolphins inhale, everything goes straight to their lungs. So you do see respiratory concerns with dolphins at times. They also are prone to stomach issues. Over my years here, we’ve had quite a few that have had even stomach ulcers that you have to treat. So those are some of the things that we watch very carefully for. There are others, obviously, they can get bacterial infections just like us. They can get fungal infections. They can get cuts and wounds that we can treat.

GILGER: And are those things more important to watch for when you have dolphins in a less natural setting, like the dolphins that are living in a place like a pool as opposed to a place like the ocean?

ERB: I would say it really depends on your environment. You know, any place can be a risk. We are very careful here, for example, when we do any kind of digging on land, coral dust can be stirred up so we’re always hosing down, you know, dust or anything that could be a potential problem for them. So it’s really managing your environment. There are some cases where I believe indoor dolphinariums where the dolphins are protected from what’s airborne is an even more pure and pristine environment. In other words, you know, bacteria and things cannot get to them as much if their water is treated. Our dolphins swim in the Gulf of Mexico. They are exposed to what is in Gulf water. What if they eat a live fish, which they do sometimes? They can get a parasite that wouldn’t be introduced to a dolphin in a tank scenario where they’re eating only frozen fish that is thawed and doesn’t have any, you know, bacteria in it. So that’s a tough one. I think it could go either way.

GILGER: Yeah that makes sense. So I wonder if you can give us a sense of, like, within this world of people who work with dolphins, is there a sense that it’s unfair or it shouldn’t happen that dolphins are kept in unnatural environments like this? Or is it something like you’re saying, like it’s more dependent on the care that they’re given in those places?

ERB: Dolphins are so adaptable. … I have not worked at an indoor facility, but I know trainers who have and I’ve interacted with them where they (the dolphins) look as content and as happy as the dolphins I see out here that I play with every day. It really does come down to, are you giving them the right environment, the right care? Are you providing the highest quality of fish? Are you giving them a balance in their diet? Because a fish is not a fish is not a fish. We actually check the calorie content of the fish our dolphins eat, and they have to have a 50 percent part of their diet as fatty fish, because some fish has more fat in it. So making sure they have exactly what they need in their diet, the care that they need, you know, the relationships with the people around them, which I think are very enriching to them, I think all of that goes together to give them the right living environment. And I think it can happen either in the natural habitat or in an indoor situation.

GILGER: I want to talk lastly then about the sort of risk-benefit comparison here, right? Can you tell us a little bit about the benefits you’ve seen in working with dolphins in this kind of setting to public education, to letting people get up close and personal with animals like dolphins, and whether you think that’s worth it, especially when it comes to keeping dolphins in a place like an indoor captive environment?

ERB: Oh, my gosh. Absolutely. What the dolphins do for people when people are able to make that connection with them is life-changing. I’ve seen it, I’ve been doing this for almost 40 years and I’ve had the pleasure of working with the general public coming in and watching them meet and connect with the dolphins, up to and including, you know, children with special needs, wounded warriors. So our species, humans, we require this connection to care about an animal and to care about them is to care about the ocean and to care about the planet. So I believe that the role these guys play, the ones that are ambassadors then that live with us, are really helping change the world for the better. Every person they connect with, you turn them into an ambassador. You turn them into a conservationist. And that’s really our goal.

GILGER: So what do you think, then, should be done in a situation like the one we find ourselves in here, where there are protests going on, lots of people saying we should not be keeping dolphins and environments like this at all? “It’s unfair, it’s like a circus.” What would you say to them?

ERB: First and foremost, the dolphins deserve the most respect, the best care, the best welfare. They come first. And that’s always the way we’ve done it at Dolphin Research Center. You can do that. You put all of that first and then take that and share that with people. Share who they are, share how special they are as a species. It’s not the same to look at something on a video screen or to go to a virtual reality show and have a dolphin swim past you as it is to look into the eye of a living, breathing dolphin and have them look back at you and have them spit water at you or do something that makes that personal connection happen. I believe that there will always be a need for that in our world. But I believe it has to come putting them first. Giving them the respect they need and everything they need. And then it should fall into line. There’s no other way to do it.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.