The fate of Lake Powell on the Utah-Arizona state line is the second largest reservoir on the Colorado, behind Lake Mead. Both are under considerable stress from overallocation and the aridification of the West. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC/LightHawk)

GREELEY, Colo. – The seven states that rely on the Colorado River for water haven’t been able to finish a series of agreements that would keep its biggest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, from dropping to levels not seen since they were filled decades ago.

Five states — Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming and Nevada — are done. So is northern Mexico. But California and Arizona failed to meet the federal government’s Jan. 31 deadline to wrap up negotiations and sign a final agreement.

The Colorado River is stressed. Simply put, the vast, highly managed system of reservoirs, rivers and streams has a fundamental imbalance between supply and demands, a gap that’s growing due to long-term warming and drying trends in the Southwest.

The overall Drought Contingency Plan, made up of agreements between the river’s Upper and Lower basins, is designed to rein in water use and — at least for six years — prevent the whole system from crashing.

An irrigation canal outside Poston, Arizona, carries water from the Colorado River to alfalfa fields in La Paz County. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

Without the plans in place, the Bureau of Reclamation, which manages power and water in the West, has issued a new deadline of March 4 for the seven states to finish the plans or it will ask the state’s governors for ideas on solving the region’s water-scarcity conundrum.

“We’re at a point where two roads are diverging in the woods,” Commissioner Brenda Burman told reporters Feb. 1. “And we need to decide which path we’re going to follow.”

The first path is the one the seven states are on now, where the parties are working collaboratively to finish the plans and put them into action themselves. Some language in the plans would then need approval by Congress and President Donald Trump.

The other path, Burman said, involves invoking the federal government’s “broad authority” to manage water distribution in the river’s Lower Basin (Arizona, California, Nevada and northern Mexico). But as tensions rise in some of the areas where the plans remain unfinished, some users are ready to challenge that federal authority.

Let’s go through a few points to understand where the drought plans stand now:

1. Arizona did and didn’t meet the deadline

Hours ahead of the Bureau of Reclamation’s deadline of midnight Jan. 31, a group of Arizona lawmakers and water users gathered in the state Capitol to watch Gov. Doug Ducey sign a resolution giving the state’s top water official the ability to sign onto the Drought Contingency Plan.

The signing was a celebration, a culmination of months of discussion in the state that laid bare hard truths about Arizona’s water past, present and future.

Earlier in the day, as the Legislature prepared to vote on the measure, House Speaker Rusty Bowers talked about just how hard it has been.

“There are hundreds and hundreds of people who’ve worked on these two bills that we have before us,” said Bowers, a Republican from Mesa. “All kinds of associations and groups have focused their attention on this. And we hope that this, as has been declared, this first step, will be beneficial to all of us.”

Negotiations brought in some groups that hadn’t been included before, such as the Colorado River Indian Tribes, who live in western Arizona.

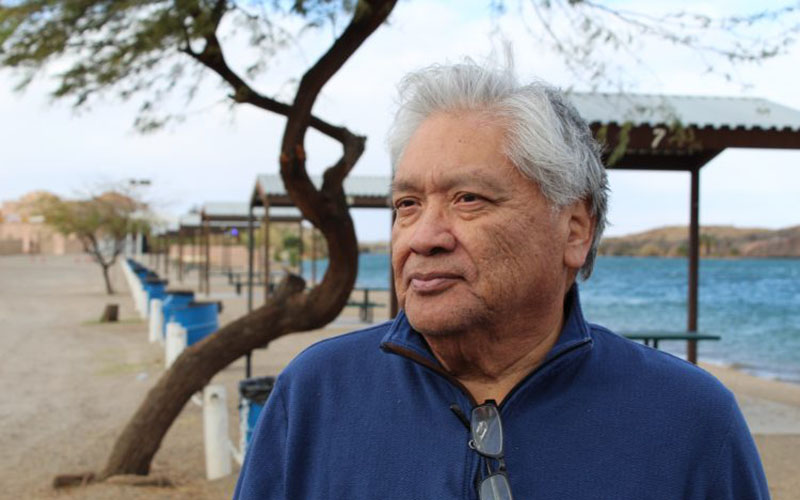

“This was our first run at (the Drought Contingency Plan) and we were very confused,” tribal Chairman Dennis Patch said. “And we’re a lot smarter now. We hope to continue to work with the state on all water issues that come up.”

Dennis Patch is chairman of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, whose land straddles the river. Patch was involved in negotiating Arizona’s portion of the Drought Contingency Plan. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

But while Arizona was celebrating its milestone, the federal government crashed the party, saying the state hadn’t done enough for the deal to be considered “done.” Leading up to the deadline, the federal government had been vague on what “done” actually meant. That led to claims that the goalposts for completion had been moved at the last minute.

Commissioner Burman said additional agreements among the state, individual water districts and tribes were left incomplete. The federal hammer would remain poised until those groups signed on.

“We met the deadline and the federal government is NOT in charge of our water,” Ducey spokesman Patrick Ptak said in an email to reporters. “It’s time for others to do the same.”

2. River’s biggest user calls the deadline ‘coercion’

California’s Imperial Irrigation District, the single largest user of Colorado River water, hasn’t been shy about its concerns over the declining Salton Sea in drought negotiations.

Since early 2018, the district’s board has said it won’t sign a broader deal until more resources are provided to manage the Salton Sea’s expanding shoreline and its spiking salinity levels. A 15-year-old agreement led to a transfer of water from the district to growing cities in Southern California. That and increasing irrigation efficiency have led to the decline of the lake, which relies mainly on farm runoff, causing environmental and public health problems as it shrinks.

California, too, was singled out by Burman for failure to meet her Jan. 31 deadline, a fact that ruffled feathers at the irrigation district.

“No federal coercion was needed to reach this point of near completion,” district board member James Hanks said at a Feb. 5 special meeting. “And we don’t need it now.”

Hanks said Burman has “dodged questions” about Salton Sea mitigation funds, and about Reclamation’s role in addressing the lake’s growing list of problems. He also challenged whether the federal government truly has authority to meddle in Colorado River allocations and entitlements.

Although the Drought Contingency Plans focus their attention on preserving water levels in Lakes Mead and Powell, Hanks said the Salton Sea is part of the broader Colorado River system, too, and its future should be included in the negotiations.

“Are the golf courses of Phoenix, the fountains of Las Vegas more important than the public-health crisis at the Salton Sea?” Hanks asked.

The Imperial Irrigation District is seeking a federal match of $200 million in farm-bill funds for projects at the Salton Sea. Those funds have not yet been allocated. In December, district board members said they’d support the Drought Contingency Plan if three conditions were met, one being that the board would be able to vote on a full package of agreements when they were done. That hasn’t happened yet.

Exposed shoreline at the fast-shrinking Salton Sea has contributed to the Imperial Valley’s high rates of adult and childhood asthma. Funds to mitigate the lake’s future problems has thrown a wrench into the completion of broader agreements on Colorado River water use. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

Water managers seem to agree that states need to use less water from the river. But when it comes down to who actually uses less, that’s when the tension starts to rise.

“This is where the rubber meets the road, or where the raft meets the river, I don’t know what the metaphor is,” said John Berggren, a policy analyst with Western Resource Advocates, a Boulder, Colorado, environmental group.

“That’s where you get into the issues and get into the real wickedness of the problems because you’re dealing with people’s livelihoods, you’re dealing with people’s values, you’re dealing with long-term, fundamental changes to winners and losers.”

Western Resource Advocates receives funding for some of its work from the Walton Family Foundation, which also provides funding for KUNC’s Colorado River coverage.

3. Once the plans are done, harder negotiations begin

If they’re finished, these deals are scheduled to expire in 2026.

Some have criticized the Drought Contingency Plans for not going far enough to solve the region’s water problems. Even the name of “Drought Contingency Plan” seems to suggest we’re dealing with a temporary dry period, rather than an overall shift in climate.

John McClow is general counsel for the Upper Gunnison River Water Conservancy District and an alternate commissioner on the Upper Colorado River Commission.

“Most of the policymakers in the West are persuaded that we have aridification rather than drought,” McClow said. “Many folks now are saying, ‘This is what we can expect. It’s not going to get better.'”

For now, that shift is in the attitude of leaders, and it isn’t taking center stage in water policy. The current plans have been crafted as a response to shortcomings in river guidelines agreed to in 2007, when water leaders were grappling with the first few years of a dry period that has lasted two decades.

Climate change and over-allocation are thorny issues that will come up almost immediately once Drought Contingency Plans are finished.

The 2007 guidelines are set to expire in 2026, and water managers are required to begin negotiating that new agreement next year. McClow said as soon as water managers wrap up these Drought Contingency Plans, they immediately have to take on a new set of even harder negotiations, and the current process to keep the reservoirs from crashing will likely make that renegotiation only marginally easier.

“It’s going to be hard no matter what,” McClow said. “Both basins have ideas about things that need to be fixed and they’re not compatible in some cases. It’s going to be a difficult negotiation.”

Those talks are supposed to render a long-term solution. But the weather in the near term adds a degree of uncertainty, too. Many streams in the basin are projected to have less than average flows throughout this spring and summer, a symptom of an ongoing drought hangover from 2018.

And that could end up adding even more pressure to the river and the people in charge of managing it.

Even so, the process in Arizona has some water managers hopeful about the next round of talks there.

“Over the last five to 10 years what I’ve noticed as a positive is, those tribalistic instincts seem to be going away,” said Shane Leonard, general manager of the Roosevelt Water Conservation District in central Arizona. “They’re definitely still there. But they’re not as hard as they used to be.”

Luke Runyon reports for KUNC, based in Greeley, Colorado. Bret Jaspers reports for KJZZ in Phoenix.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.