The Central Arizona Project canal system spans 336 miles and brings 1.5 million acre feet of water from the Colorado River as far south as Tucson. (Photo by Lillian Donahue/Cronkite News)

ELOY – Arizona lawmakers beat a midnight deadline set by the federal government by just a few hours Thursday, agreeing on a plan to balance drought and water supplies in the Colorado River Basin.

The goal is to keep water levels in Lake Mead from plummeting so low there wouldn’t be enough water for the millions of people throughout the Southwest who depend on it. For Arizona, that could mean losing about a seventh of the state’s annual water allotment to the Central Arizona Project, which provides much of the state’s water.

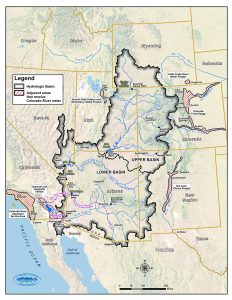

The Colorado River Basin spans nearly the length of Arizona, but its impact is felt across the Southwest. See a larger version of the map here. (Graphic courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation)

Although Arizona has signed off on the drought contingency plan, California’s Imperial Irrigation District may delay the basin-wide deal. According to the Desert Sun, the district wants $200 million to restore the Salton Sea.

Water managers expect Mead’s levels to drop low enough that by May of this year, there would be a shortage declaration and reduced water allocations. The plan Arizona approved will mitigate those cuts.

Arizona was the last of the three Lower Basin states to approve a Drought Contingency Plan, and it’s the only state that required legislative action to put the plan in place. If Arizona had missed the midnight deadline, the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which manages water and power in the West, said it would impose its own drought plan on the entire Colorado River Basin.

The plan is a stop gap approach to manage water shortages and will be in place until 2026. Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, which make up the Upper Basin, signed their drought contingency plan in December.

“Lake Mead is essentially overallocated,” said Sarah Porter, who directs the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University. “There is more water going out of Lake Mead than coming in.”

What the drought plan would do

According to Porter, part of the plan sets a schedule of voluntary cuts that users agree to take to keep lake levels sustainable. The plan also designates rules on when users can take water out of the reservoir.

The plan, which had bipartisan support, aims to keep lake levels high enough to try and avoid a catastrophic shortage in Arizona.

“Arizona has a really hard task because we would take the largest cuts of any of the users, and we need to have our legislature approve singing on to DCP,” Porter said.

What’s behind the plan?

The 19-year drought has forced Southwestern states to orchestrate a plan for more sustainable water usage from the Colorado River.

If the lake levels dip too low, Arizona consumers could also see higher water rates.

This isn’t the first time Arizona has experienced hard policy reform to ensure there’s a water supply.

The lower basin agreed to a plan similar to the DCP in 2007, though the cuts weren’t nearly as dramatic as those Arizona faces now.

“We’re looking at significant decreases in Colorado River deliveries,” Porter said.

The Bureau of Reclamation will declare an official shortage and water cutoffs if Lake Mead’s water level drops below 1,075 feet above sea level. That hasn’t happened yet, but water managers predict it could occur as early as May. At 1,050 feet, stricter cutoffs would be imposed.

Who would suffer the most pain?

Arizona has sealed a bittersweet arrangement that addresses how water users would share the pain of a water shortage, Porter said.

Pinal County farmers will be among the first users to take a cut if there’s a drought declaration.

“Long term, those Pinal County farmers are looking at needing to have other supplies of water,” Porter said. “The DCP has included provision for those farmers to be able to develop or redevelop infrastructure to pump groundwater out and they can use groundwater for their operations.”

Brian Rhodes, who farms 15,000 acres of land near Eloy, believes that will be devastating for the agriculture industry.

“Without some type of mitigation proposal, the alternative is Pinal County farmland no longer becomes viable for a large percentage,” Rhodes said. “That is detrimental for not only the farmers like myself, but you’ve got so many industries that are being supported by the farming operation.”

Pinal County ranks in the top 2 percent nationwide in the total value of agricultural sales, according to a study from the University of Arizona’s Agriculture and Resource Economy.

Rhodes says regardless of the Legislature’s decision Thursday, agriculture still will be forced to increase sustainability efforts.

“Even under the mitigation and other proposals that are on the table, we’re still looking at a lot less available water going forward,” Rhodes said. “The drought is something that’s out of anyone’s control. We’re going to all have to adjust to a new frontier as far as water availability and from what we’ve been used to.”

The plan provides farmers with more water than they would receive if lawmakers had been unable to reach a decision, said Dave Roberts, chief water resources executive for Salt River Project.

“I wouldn’t say they’re in good shape, but they’ll be better off than they would have been,” he said.

Cronkite News reporter Lillian Donahue contributed to this story.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.