Height, rather than age, determines when a saguaro begins to grow arms. More arms means more blossoms and fruit, which helps the cactus propogate. (Photo by Stina Sieg/KJZZ)

Martin Wojciechowski, an evolutionary biologist at Arizona State University, and his colleagues hope to unlock the secrets of how and when saguaros evolved to live only in the Sonoran Desert. (Photo by Mariana Dale/KJZZ)

Kevin Hultine (left) is a plant physiologist at the Desert Botanical Garden, where Raul Puente-Martinez is curator of living collections. (Photo by Jackie Hai/KJZZ)

PHOENIX – Saguaros are an enduring icon of the American West, towering sentinels with shapes that are distinctive yet wonderfully, wildly divergent. Arizonans and visitors alike are fascinated by these cactuses, which can live more than 200 years, stand 60 feet tall and weigh more than 2 tons.

The saguaro even serves as the sole emoji for cactus on iPhones.

But what makes saguaros unique? Why do they only grow in the Sonoran Desert? Why do some grow many arms and others none?

Scientists are busy trying to unlock the secrets to the slow-growing Carnegia gigantea.

In a small, windowless room in Arizona State University’s Life Science Center in Tempe, dozens of 2-year-old saguaros grow in a bath of artificial white-yellow light.

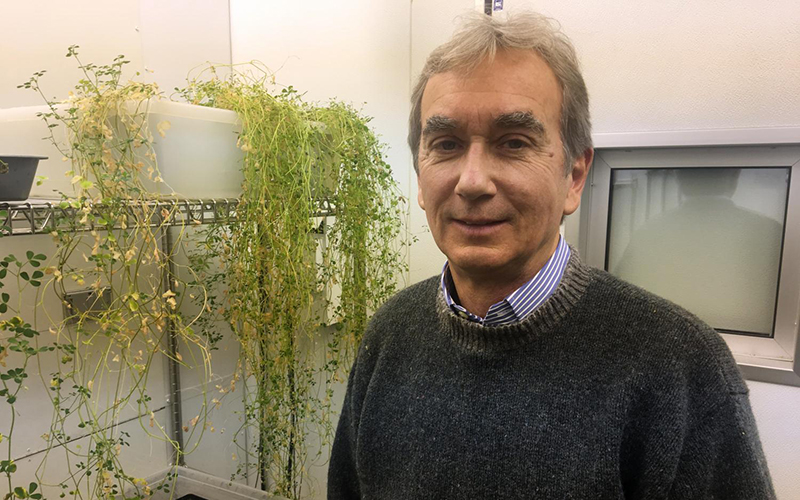

“These look like just green thumbs popping up out of the soil with, you know, lots of spines,” said ASU evolutionary biologist Martin Wojciechowski, who grew the cactuses from seed. They first emerge from pinhead-size black seeds as “diamond-shaped green blobs,” he said.

These saguaros are special because they’re descended from the first fully genetically sequenced saguaro, SGP-5 F1, which stands for Saguaro Genome Project, cactus No. 5, the first filial generation. Until it fell in a monsoon storm, No. 5 grew on Tucson’s Tumamoc Hill.

Wojciechowski and his colleagues hope to unlock the saguaros’ secrets. They only grow in the Sonoran Desert, generally below 4,000 feet elevation, which includes northern Mexico, Arizona and a little bit of California. The Sonoran has two rainy seasons, and summer monsoon rains are thought to be key to saguaro propagation.

“We would like to understand how and when those adaptations to life in a hot arid environment evolved,” Wojciechowski said.

Those genes might also hold clues as to why the saguaro grows into such a distinctive shape. But there are a few things scientists already know.

For one, gravity shapes all plants, including saguaros.

“They know which way is up,” Wojciechowski said. “They know which way is down, and they orient themselves in that sort of vertical direction.”

Saguaros grow from the tips of their stems and their roots, which are relatively shallow and spread out. Like an accordion, a saguaro’s girth fluctuates with rainfall. When there’s more water, they expand and vice-versa.

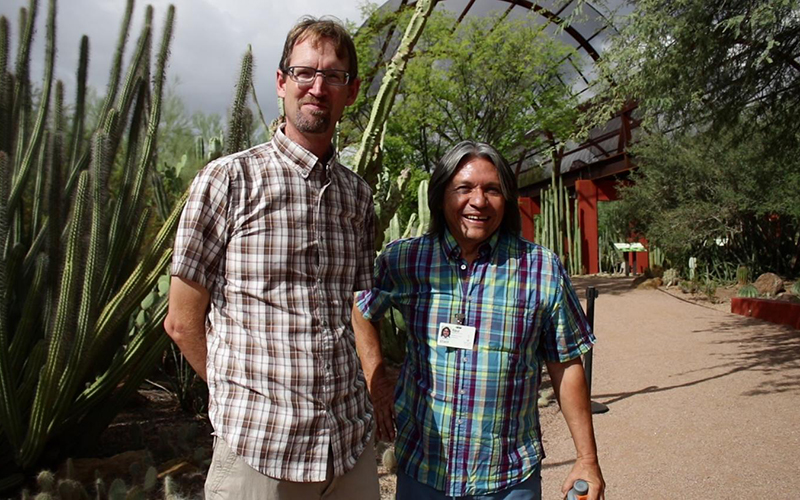

“If you have a great big stem, lots of storage, but you grow really slow, the likelihood is that you can persist for a long time,” said Kevin Hultine, a plant physiologist at the Desert Botanical Garden in east Phoenix, where more than 1,000 saguaros stand.

Saguaros are estimated to live to 200 years or older. One key for survival in the desert is how much water they can store.

Saguaro arms first emerge when the cactus is about 10 feet tall, although some never grow arms. Contrary to popular belief, Hultine said, the arms don’t occur at a specific age. How fast the saguaro grows depends on where it stands and how much water is available.

He pointed to a saguaro arm that’s several feet long.

“I would say that, right now, it’s probably storing 30 to 40 gallons of water just in that arm,” Hultine said, estimating the weight at 250 pounds.

So the more arms a saguaro has, the more water it can store. But that’s not the only reason for the arms.

“When you think about the goal of producing all these arms is to produce more flowers, so you have more sites that can be visited by potential pollinators,” Hultine said.

More pollinators means more fruit, more seeds and a greater chance of reproducing.

Saguaros’ height helps them stand out to hungry bats, bees and birds that will pollinate their flowers.

Saguaro arms can weigh hundreds of pounds, which is why the arms curve upward – more like a Y than a T.

“Think about if you held your own arms out and you had weights at the end of your wrists,” Hultine said. “It would get pretty heavy, right?”

The biomechanics of the shape make it easier to support such weight, he said.

But not every saguaro looks like the cactus emoji. Why?

“It is hard to explain,” said Raul Puente-Martinez, curator of living collections at the Desert Botanical Garden. He has studied cactuses for decades; his college thesis was on the prickly pear.

One explanation is that a hard frost can damage a saguaro’s skeleton, or ribs. The usually strong, fibrous ribs are weakened and can’t hold the weight of the arm, causing it to droop.

Mark Dimmitt, director of natural history at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum near Tucson, told the Arizona Daily Star that staff members have noticed more freeze damage on saguaros on lower ground.

Saguaros can be difficult to study because they grow so slowly, often just a few inches a year.

“We tend to think in nature that everything has an evolutionary purpose,” Hultine said, “but there is some random events that happen that may not necessarily increase the fitness of the plant, but if it’s non-lethal, plants will persist.”

For example, some saguaros never grow arms.

“Within a unique species, there are unique individuals that you come across all the time,” Hultine said.

The crested, or cristate, saguaro is an example of a persisting oddity. These cactuses have fan-like growths.

“That growth, vertical growth, is interrupted,” Puente-Martinez said. The cells divide horizontally instead.

Side note: The Desert Botanical Garden once was home to a crested saguaro stolen near Quartzite and rescued from a Las Vegas nursery, where it was priced at $15,000.

No one knows exactly why the crested variation happens, but some experts suspect damage from frost or lightning, a genetic abnormality or hormonal quirk.

This story was inspired by a question from Carol Gibson as part of KJZZ’s Q&AZ reporting project.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.