GREELEY, Colo. – After one of the hottest and driest years on record, the Colorado River and its tributaries across the Southwest are likely headed for another year of low water.

That’s according to an analysis by the Western Water Assessment at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Jeff Lukas, the researcher who authored the briefing, urged water managers throughout the Colorado River watershed to brace themselves for diminished streams and a decreasing likelihood of filling reservoirs left depleted by nearly two decades of drought. The analysis relies on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Geological Survey and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, among other agencies.

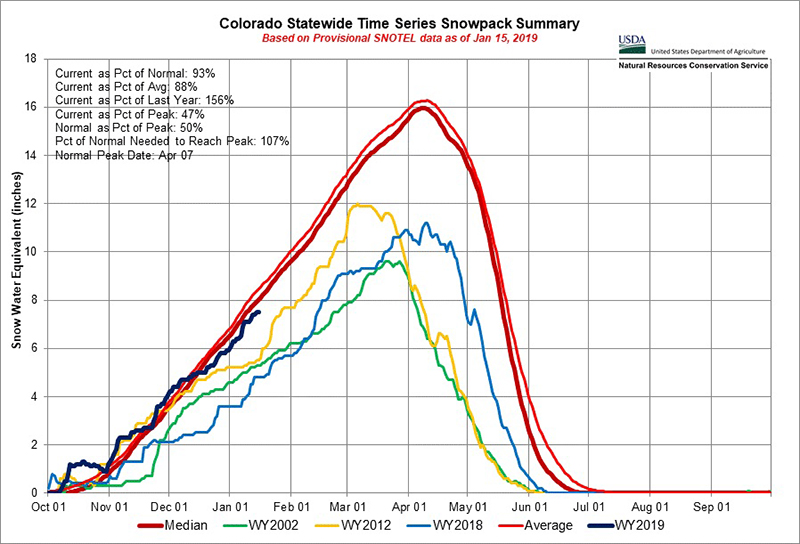

That dire prognosis comes even as much of the Southern Rocky Mountains have seen a regular cycle of snowstorms this winter.

“The snowpack conditions for Colorado and much of the Intermountain West don’t look too bad,” Lukas said. “They range from ‘meh’ to ‘OK.'”

Snowpack that feeds the Colorado River ranges from 75 percent to 105 percent of normal. Snowpack in the entire Upper Basin – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – is sitting at about 90 percent of normal for this time of year.

So with an “OK” snowpack in the Upper Basin, which supplies most of the water in the Colorado system, we should be in good shape, right?

Not necessarily. If you’re just looking at snowpack to gauge how well a winter is going, Lukas said, you’re doing it wrong.

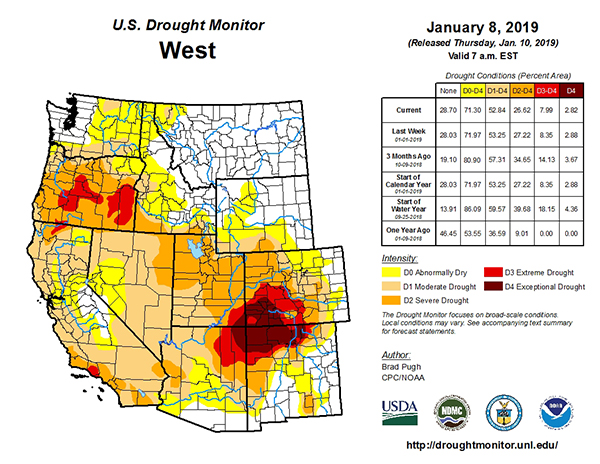

The record hot and dry conditions during 2018 further sapped the ground of its moisture. Leading into this winter, “that puts us in a deep hole,” Lukas said.

Put another way, across the Southwest, we’re living in a drought hangover. And it’s going to take a lot more snow to pull us out of it.

Lake Powell, the first major reservoir the Colorado hits on its 1,450-mile journey to the Gulf of Mexico, is projected to see 64 percent of its average inflow, according to the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. That translates to a one-year deficit of more than 5 million acre-feet of water. An acre-foot is enough water to supply roughly one to two households for a year.

“That’s not as bad as what happened last year, but it’s pretty close,” Lukas said. “That’s going to just drain the big reservoirs – Powell and Mead – even further.”

The less-than-hopeful projections come as water managers and users throughout the river’s 246,000-square-mile watershed, particularly in Arizona, attempt to curb use and mitigate reductions in the face of declining reservoirs. Levels are dropping due to an ongoing aridification within the basin, a product of climate change, and chronic overallocation of resources.

Drought contingency plans, which the seven Colorado River Basin states have been hammering out for years, have a federally imposed deadline for approval of Jan. 31, and another dry winter will put even more pressure on their negotiations.

“This certainly imparts more urgency to that mission to get those plans in place knowing that we’re likely to have a below-par if not well below-par year in the Upper Colorado,” Lukas said.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Subscribe to Cronkite News on YouTube.