Diana Calderon looks over a proof she made from a linoleum carving inspired by a 2016 trip to Teotihuaca, a Mesoamerican city in the broad Valley of Mexico. (Photo by Matthew Casey/KJZZ)

PHOENIX – Artist Diana Calderon used a small brayer to spread dark ink on a glass plate as she demonstrated how to make a print from a linocut.

“Most of my work is about crossing barriers and borders and boundaries,” she said.

Born in Ciudad Chihuahua, Mexico, Calderon has been migrating for much of her life, which made her feel displaced as a child. She moved back to Phoenix a year ago from Dallas, where she’d lived three years.

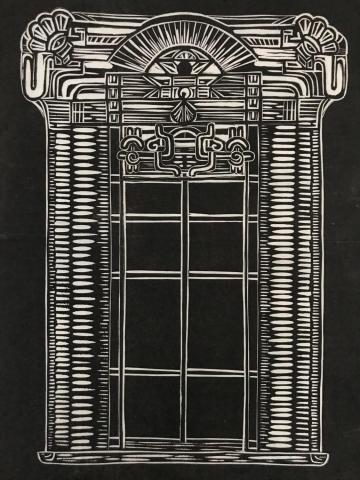

“En Teotihuacan” is a linocut print by Diana Calderon. She has created several variations of the project, which was inspired by a 2016 visit to Teotihuacan. (Courtesy of Diana Calderon)

On a recent Wednesday, Calderon stood in the courtyard of Phoenix Art Museum, making a print from a linoleum carving that was inspired by a trip in 2016 to Teotihuacan, an ancient city in central Mexico known for its massive, elaborately carved stone temples and monuments.

“I was really drawn to this architectural masterpiece,” she said, referring to part of the site called Quetzalpapálotl.

Calderon would normally have to travel to Mexico for this kind of artistic stimulation. But through Jan. 27, she can get at least a touch of inspiration at the museum, where artifacts from the Mesoamerican city are on display.

“It’s just more than exciting to have a piece of that, here in Phoenix, here in a museum,” she said.

“Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire” includes archaeological treasures that also are considered fine art. The pieces were excavated from Teotihuacan, which the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization has designated a World Heritage Site.

More than 2,000 years old, Teotihuacan in its prime was a diverse city of migrants. Since the Mexican Revolution in the early 1900s, it has become an integral part of Mexico’s national identity.

Teotihuacan’s secrets still are being unlocked. Some artifacts in the exhibit were excavated from a tunnel discovered less than 20 years ago. They may just be the tip of the iceberg of what’s in the underpass, said Gilbert Vicario, Selig Family chief curator of Phoenix Art Museum.

“It will probably be a 30-year project to really unearth everything they’ve discovered in that tunnel,” he said.

Vicario went to Teotihuacan for the first time as a 13-year-old visiting family in Mexico City, which is about 30 miles southwest of the site.

“I was so excited, I ended up stepping on my (dental) retainer,” he recalled. “That was kind of my inclination. I was always drawn to art.”

Teotihuacan was home to a migrant population, according to a guide of the exhibit published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco de Young. There’s evidence Teotihuacanos spoke multiple languages and accepted a variety of religions.

Trade routes stretched to the seas and Central America, Vicario said.

“So the Zapotec Indians of Oaxaca had an influence in Teotihuacan,” he said, as did “the Olmecs, the Mayans.”

Teotihuacan society collapsed about 650. The Aztecs rediscovered the city centuries later and came up with the name Teotihuacan, which means “place where the gods were created.”

There have been multiple excavations since. The most recent dig, which Vicario said was a key reason for bringing “City of Water, City of Fire” to Phoenix, started after rain opened what appeared to be a sinkhole.

The hole turned out to be a tunnel leading beneath the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, a symbol adopted by Aztecs after they migrated into the Valley of Mexico.

“(The Aztecs) ended up naming a culture that really left nothing,” Vicario said. “They left no evidence of a written language, and it’s really been just a puzzle to try (to) put together who they were, what they stood for, what was left behind.”

The Aztecs’ recovery of Teotihuacan was one of several key points in history, said Seonaid Valiant, curator of Latin American Studies at the Arizona State University Library.

“Teotihuacan is a historically significant site because since the time it was built, it has been in use as either a political or religious site,” she said.

Another key development came about a hundred years after Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821. Teotihuacan was part of a broader government strategy to separate the country from its former colonizers.

“They started promoting the indigenous symbols as a way of creating their own national identity,” Valiant said.

The result of the effort, which included an excavation of the site, as well as some revising of history, survived the Mexican Revolution. Folk movements in the 1920s and ’60s helped bolster Mexico’s pride in its indigenous roots. Now living in a modern country, young Mexicans still feel a strong connection to Teotihuacan.

“And you are accustomed to a lifetime of seeing these iconic images over and over again,” Valiant said.

As daylight faded in the Phoenix Art Museum courtyard, Diana Calderon used a small press to make a print of her carving inspired by Teotihuacan. The 2016 trip led to a personal breakthrough with her art, which has taken her career in a positive direction.

“I became more brave with my own work,” she said. “I was already working on being honest and vulnerable with my work. But it just gave me the extra strength to be brave, because I was afraid to be me.”

Calderon plans another “migration,” in 2019, to make her third visit to Teotihuacan. For now, she can draw inspiration from its artifacts on loan to the Valley of Sun.

Connect with us on Facebook.