GREELEY, Colo. – Early season snowfall in some parts of the Colorado River Basin have raised hopes of a drought recovery. But that optimism is likely premature.

In some parts of Colorado, higher-than-average snowfall in October and early November has allowed ski resorts to open early. That was encouraging, considering last year’s season got off to a dismal start.

Mountains that feed the Colorado River’s main channel, as well as the Yampa and White rivers, all have above-average snowpack. Both basins are home to ski resorts in Steamboat Springs, Vail, Aspen and Summit County. But snowpack in the Green, Dolores, San Juan and Gunnison river basins is below average for this time of year. The entire Upper Colorado River watershed – and its 118 snowpack measurement sites – is currently at 77 percent of the 30-year median.

Most streams and rivers that make up the sprawling seven-state Colorado River Basin are fed by melting Rocky Mountain snow. Last winter’s record heat and dryness across large swathes of the basin states – Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, California, Arizona and Nevada – continued the deep, enduring drought in the region.

Although snow has returned to the Rockies this winter, the drought isn’t over, said water policy analyst John Berggren of the environmental group Western Resource Advocates. The group receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which also funds KUNC’s Colorado River coverage.

“The tricky thing with drought in the West and with water supplies in the West more broadly, it’s a much more long-term slow process both to get into a drought and to get out of a drought,” he said.

Snowpack is prone to large fluctuations early in the snow-accumulation season. Berggren said it’s also important to look at reservoir storage, soil moisture, ecosystem health and municipal water supplies when declaring a region fully recovered from drought.

It’s also difficult to say whether a particular dry period is a short-lived drought or a manifestation of climate change, Berggren said.

Studies show the Southwest is likely to see higher temperatures and more prolonged dry periods if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rate, making the region more arid, and further blurring the line between temporary drought and permanent aridification.

The Colorado River’s legal conundrum – the fact that more water exists on paper than in the river system itself – compounds the problem, Berggren said. Several years of record-breaking snowfall wouldn’t fix the river’s fundamental supply-and-demand problem, which is why its biggest reservoirs are declining, he said.

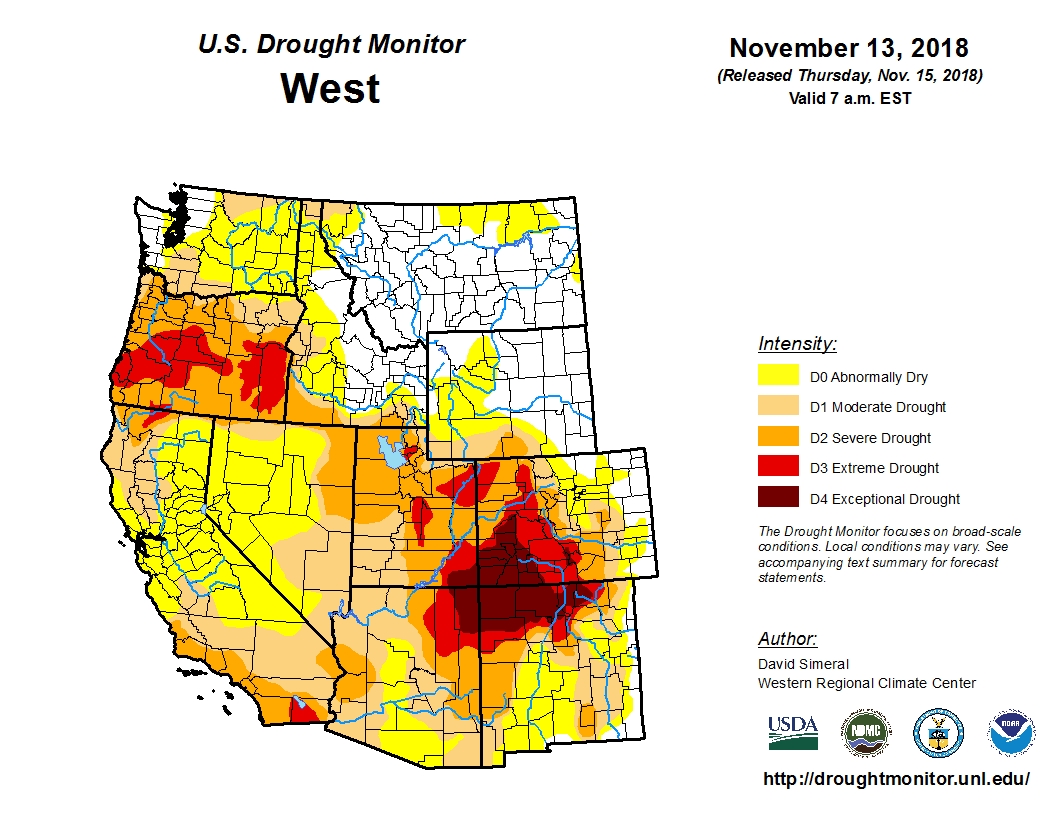

The U.S. Drought Monitor from Nov. 13 shows the Southwest experiencing extreme to exceptional drought conditions. (Graphic courtesy of U.S. Drought Monitor)

“Because of the systemic issues, you’re going to see those reservoirs to be strained and slowly to continue to decline,” Berggren said. “And so some folks might see it as an opportunity if we have a decent year. But the systemic issues are too big not to deal with regardless of what the snowpack does.”

Lake Mead is forecast to drop below a threshold in early 2020 that would trigger a first of its kind shortage declaration in the Colorado River’s Lower Basin, which includes Arizona and California, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projections show.

Long-term forecasts from the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center show much of the Southwest likely to experience higher than average precipitation and temperatures this winter.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.