Thunderstorms build up over Tempe this summer during the monsoon. Researchers at the University of Arizona are studying mud from the seafloor in the Gulf of California to better predict the intensity of future monsoons. (Photo by Jordan Evans/Cronkite News)

TUCSON – Thunder and lightning. Dust and wind. Flash floods. These hallmarks of the North American monsoon are well-known to Arizonans, and new research indicates these impressive storms have been a part of the Southwest’s climate for millions of years.

Jessica Tierney, a geologist and associate professor at the University of Arizona, leads a research team that’s analyzing mud samples taken from the seafloor in the Gulf of California.

“What we are interested in knowing about is how the monsoon is going to change in the future, and how we can prepare,” Tierney said. “But in order to do that, we have to actually go back and look in the past.”

It’s impossible to predict when and where monsoon storms will strike. But Tierney and her team’s work could help climatologists better understand the power of the North American monsoon, which hits the Southwest from June through September, and what its intensity may be like in the future.

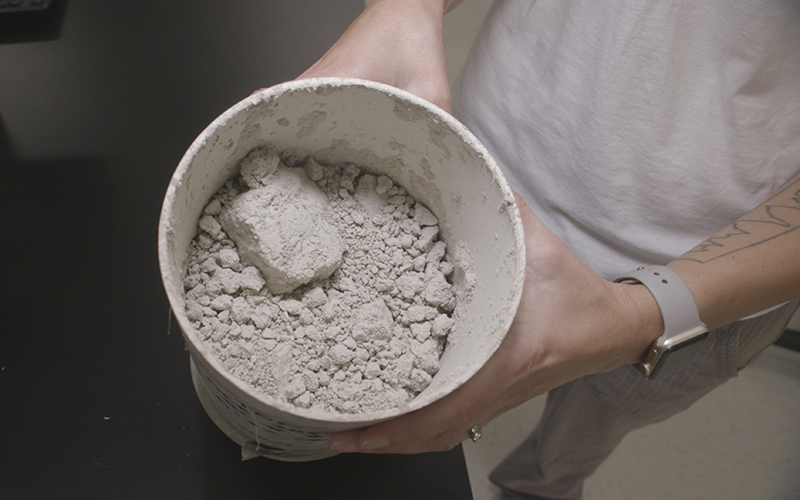

Deep-sea mud contains chemical signatures that hold secrets about the earth’s past. Researchers are studying mud to understand the intensity of the monsoon millions of years ago. (Photo by Jordan Evans/Cronkite News)

Deep-sea mud contains chemical signatures that hold secrets about the earth’s past. One area the team is looking at are the waxes that plants secrete to hold in moisture and control evaporation.

“The waxes that are growing on plants that receive more monsoon rain have a special chemical signature versus plants that were growing in times that had more winter rain,” Tierney said.

“By measuring the chemistry of these plant waxes, we can actually go back in the past and tell you how much summer versus winter rain there was.”

Tierney is more interested in summer rain because that’s when Arizona’s monsoon occurs. If her team can get a better idea of how much rain fell during the summer months of the latest ice age, they can conclude how intense the monsoon was back then.

The team has already found that the North American monsoon was suppressed but not completely gone during the latest ice age, which ended more than 11,000 years ago. Tierney said its research also suggests the monsoon has been a persistent feature of the Southwest’s climate.

The research has stirred up the interest of other scientists.

“If they can go down to deeper layers where it was a warmer period and interglacial, something where we had similar kind of CO₂ that we have now, and they can see how was the monsoon consistent then, was it more intense or was it less intense, that will be very useful information,” said Nancy Selover, Arizona state climatologist.

“Right now, global climate models don’t do a good job predicting precipitation from the monsoon,” she said, noting that the monsoon might be 10 percent wetter or 10 percent drier. “If we can get a good idea of whether the monsoon will be more or less intense, we will really have a good idea of which it will be.”

Tierney, who will be one of the authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report expected in 2021, hopes the study can be useful for policymakers.

“Our work that is done here could be very useful for water resource management. If we have a better idea on the how the monsoon could behave, it could certainly help people in the Southwest plan for future drought.”

The team is looking to collect mud compounds from even deeper layers in the floor of the Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. Tierney said that could help them answer how the monsoon acted millions of years ago, when the planet was as warm as it is today.

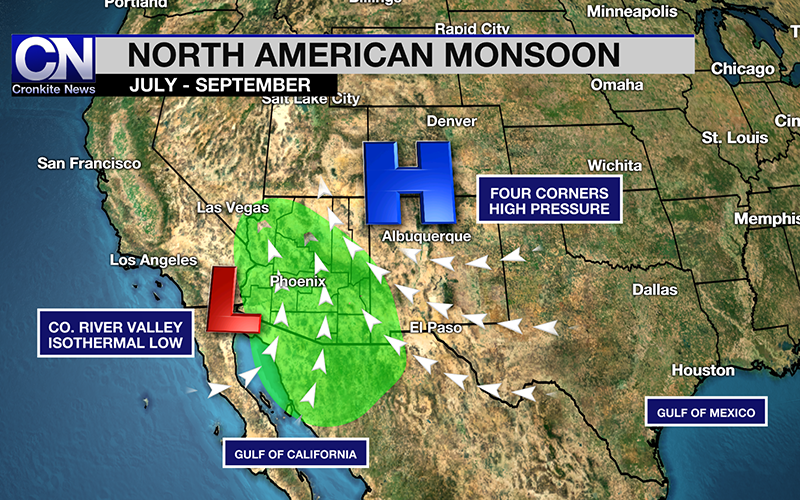

Monsoons aren’t just felt here in Arizona, but in South America, Africa and Asia. They are classified as a seasonal change in the winds in the upper atmosphere. The North American monsoon can be described as a formation of upper-level clockwise circulation, also known as high pressure, over the mountains of Mexico, New Mexico and west Texas.

This formation creates atmospheric rivers from the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of California, which bring in high levels of moisture to the deserts. The mountains across the area lift the intensive heat at the surface into the atmosphere, giving way to enormous thunderstorms.

The North American monsoon draws moisture into Arizona thanks to placement of upper level high pressure over the Four Corners region. (Graphic by Jordan Evans/Cronkite News)

-Video by Jordan Evans

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.