ARLINGTON, Va. – Richard Nguyen remembers as many as 100 men in his family’s restaurant, reflecting on their Vietnam War experiences over spring rolls and noodles.

Over the years, that number dwindled to 40, and then to 25, as the veterans moved out of the area or passed away. Last weekend, the group lost yet another member, when Sen. John McCain died from brain cancer.

It may seem unusual for Vietnam veterans to choose a Vietnamese restaurant as their favorite place to gather. But for more than 30 years the vets – many of them former prisoners of war – have been coming here on Tet, the Vietnamese new year, to reminisce and to heal.

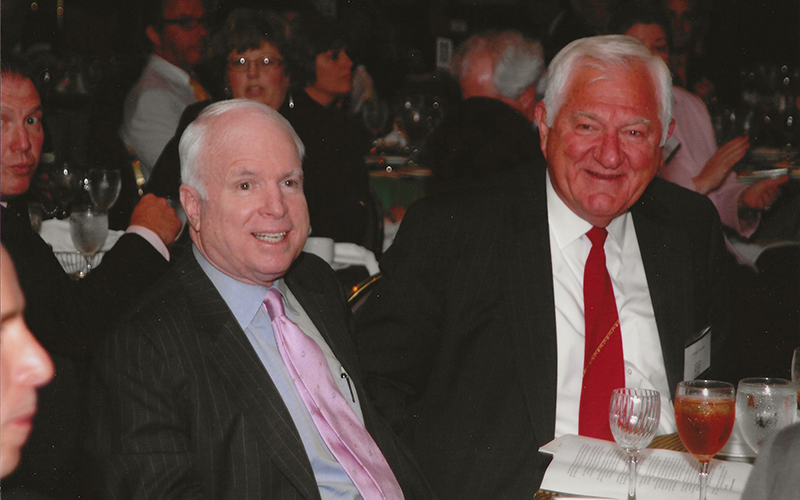

Orson Swindle today. He says it was important for former POWs like him and McCain to have a place like Nam Viet. “We had to heal. We can’t go through one generation after another hating each other.” (Photo courtesy Orson Swindle)

“We would sit there for several hours, laughing and having wonderful food, and it has just been very much a part of our lives,” said Orson Swindle, who spent 18 months with McCain in a North Vietnamese prison, the infamous Hanoi Hilton.

“John and I slept side by side in prison, so we knew each other pretty well,” Swindle said this week by phone from his home in Colorado.

Swindle said McCain made an effort to step away from the demands of his career every once in a while to enjoy a meal at Nam Viet.

“When he had a break, at any time of the year, I would get a call from his staff saying, ‘The senator wants you to see if you can pull together some of your old friends and let’s have dinner over at Nam Viet restaurant,'” Swindle said.

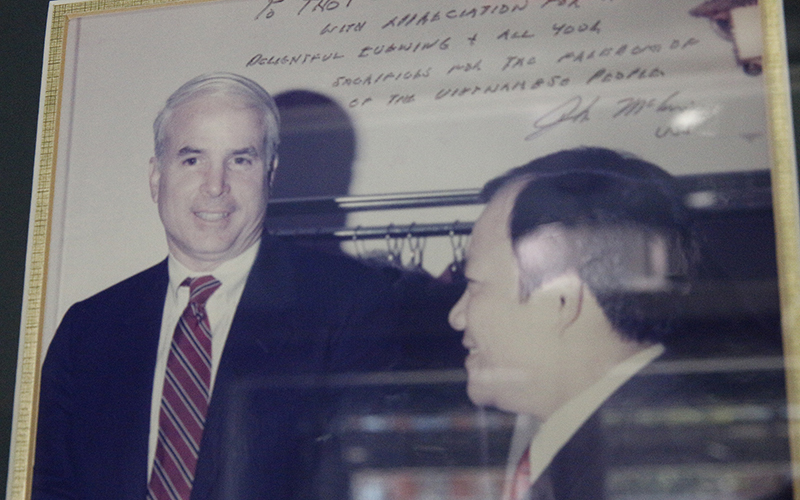

Richard’s father, Nguyen Van Thoi, who co-founded the restaurant with his wife, was a POW himself, having been imprisoned for three years for working as an interpreter for the U.S. Army during the war.

“The bond between them, in terms of being captured and being held captive, is pretty much why this event exists,” Nguyen said of his father’s relationship with the other POWs.

Nguyen, 34, was a child when the first reunion dinner was held at the family’s previous restaurant, My-An, in what used to be Arlington’s Little Saigon, a collection of Vietnamese shops and restaurants.

The reunions were held around the Vietnamese new year, which falls in spring.

“The mandate was that if it falls on a Super Bowl Sunday, we do it the week prior or the week after,” Nguyen said. “But for the most part, it’s always been between the end of January and mid-February.”

Nguyen believes that the restaurant would not be what it is today without the support from POWs over the last several decades.

“Nam Viet restaurant is indebted to the POWs, ever since we first opened up, and we’ll do anything we can do to help them out,” he said.

Growing up, Nguyen made sure to give the veterans their space during the reunions, not wanting to pry into their traumatic experiences. Still, he knows that the stories told within the restaurant capture hundreds, if not thousands, of vignettes of the Vietnam War.

“If these walls could talk, I’m pretty sure they could tell you more than I could ever recollect,” Nguyen said.

Nguyen remembers McCain at the gatherings of veterans, or just showing up with family, convening at a round table in the back.

“His favorite dish was always the Vietnamese crepe, the chicken noodle soup, or pho, and crispy rolls,” Nguyen said.

He said that one of those visits came during McCain’s 2008 presidential bids, when his staff tried to make it a private event. But McCain was having none of it, and the restaurant stayed open to the public.

“There was no special treatment. He was always humble, he just wanted you to treat him as the next customer at the table,” Nguyen said. “That’s really hard to find in politicians these days.”

To Swindle and Nguyen, that’s exactly who McCain was – not a political giant or a celebrity, but simply one of the guys, someone who could share in their catharsis and their camaraderie as they worked to process their trauma and heal from it.

“We had to heal,” Swindle said. “We can’t go through one generation after another hating each other.”

Follow us on Twitter.