WASHINGTON – The government must help reverse generations of federally backed assimilation programs that left Native Americans “robbed of the ability to speak our own language,” advocates told a Senate panel Wednesday.

“A Native language is not just a language, it is the foundation of a culture,” said Lauren Hummingbird, a graduate of a Cherokee Nation immersion school and one of five witnesses before the Senate Indian Affairs Committee.

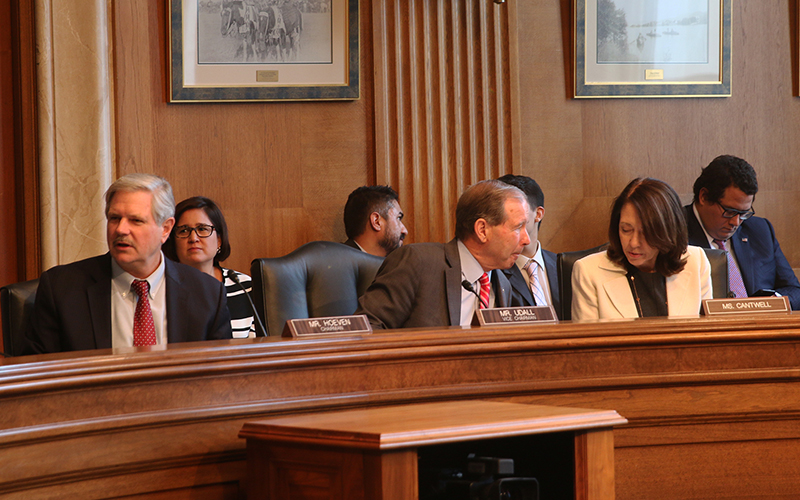

The hearing, “Examining Efforts to Maintain and Revitalize Native Languages for Future Generations,” included few specific proposals but plenty of support from senators on both sides of the aisle.

“What the Cherokee Nation has done is a really impressive move forward in terms of native languages,” said Sen. John Hoeven, R-North Dakota, pointing to Tsalagi Tsunadeloquasdi, the immersion school Hummingbird attended.

Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico, said the scores of native languages spoken in the U.S. serve an “irreplaceable role” for their speakers and that their revitalization is “crucial to the cultural identity and sovereignty” of those communities.

“Native languages are not only crucial to the communities that speak them, but they also have played an important role in our shared American history,” Udall said.

But that history is a large part of the problem, speakers said.

“After relentless pressure from non-Indian settlement of our aboriginal lands and the pressure that came with it to interact with the non-Indian community around us in English, including assimilation efforts … we were robbed of the ability to speak our own language,” said Jessie Little Doe Baird, vice chairwoman of the Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribe in Massachusetts.

“For six generations, we could not introduce ourselves or speak to our ancestors in our own language,” Baird said in written testimony prepared for the committee.

But Baird said that a decades-long project has allowed her tribe to reclaim its language, which had a written form but no living speakers remaining when they started.

-Cronkite News video by Lillian Donahue

Baird cited the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, which allowed her tribe to produce two credentialed Wampanoag linguists and more than 15 certified language teachers, as well as a variety of supplemental programs and resources to aid language learning.

“There are so many ways that the federal government, our trustee, can help us improve and advance the vitally important work of language protection,” Baird said.

Other speakers, like Jeannie Hovland, pointed to the paradox of the Navajo Code Talkers, who used their language during World War II to create a code that the Japanese were unable to break.

“Although these heroes were not allowed to use their language in day-to-day life, their languages were relied upon to communicate vital information,” said Hovland, commissioner of the Administration for Native Americans in the Department of Health and Human Services.

“We need to honor their sacrifice by keeping their languages alive along with their legacy,” she testified.

Baird emphasized the importance of maintaining a “speaker pipeline” for language programs, in which students who become fluent in a language can return to teach other subjects in the target language, creating an immersive language-learning experience.

Several speakers mentioned the Esther Martinez Act, which would dedicate $13 million for Native American languages each year from fiscal 2019 to 2023. That bill, sponsored by Udall, passed the Senate in November and was referred to the House, where it has yet to get a hearing.

Hummingbird urged senators to repair years of cultural erosion by supporting language immersion and restoration programs, including immersion schools and extracurricular programs. She said the abuses of the past “caused my people to become scared of the world, and it nearly cost me my culture.”

“Native Americans today are still coping with federal policies and decisions that negatively impacted our ancestors,” Hummingbird said. “Knowing how to speak my language not only gives me the opportunity to keep my culture and language alive, but it also shows the world that we are still here.”