WASHINGTON – More than 10 years after it was first approved, a federal loan program for tribal energy development projects will accept its first applications next month.

The Department of Energy in July said it was accepting applications for projects under the $2 billion Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program, which will provide “partial loan guarantees to leverage private sector lending” for a range of energy projects by tribes.

“It’s a good start,” said Pilar Thomas, a professor specializing in Indian energy and policy at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor School of Law. “There’s a real opportunity for them (tribes) to do something around energy.”

It’s an opportunity that’s been a long time coming: The tribal loan program was first approved in 2005 but not fully funded until Congress passed the omnibus budget bill in May 2017.

The program aims to stimulate economic growth in Indian Country by allowing the Energy Department to guarantee up to 90 percent of the unpaid interest on these loans. The first applications are due Sept. 19, with deadlines every other month thereafter.

The program will let the government “work in partnership with private-sector lenders to help them better understand the unique characteristics of tribal energy opportunities and catalyze future private-sector investment,” said Energy Secretary Rick Perry in a statement announcing the start of the program this summer.

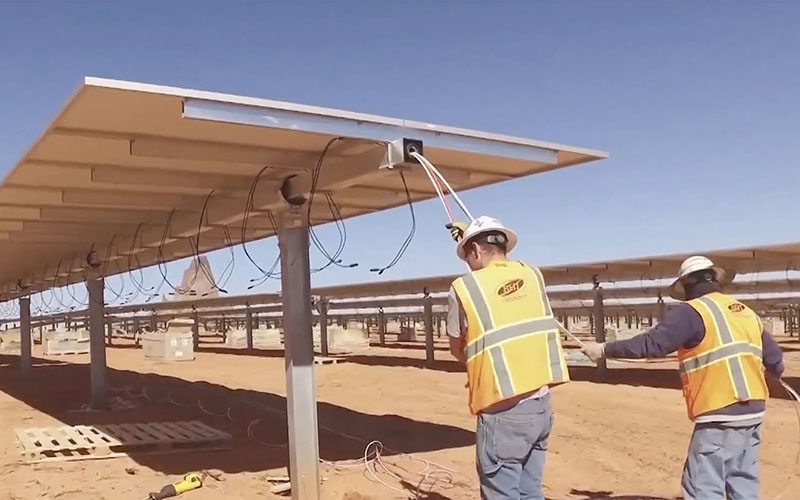

The National Congress of American Indians cites Interior Department estimates that undeveloped energy reserves on tribal lands, including coal, natural gas, and oil, could “generate nearly $1 trillion in revenues for tribes and surrounding communities.” But the loan program will be available for renewable energy projects, like wind and solar power, in addition to transmission lines and energy storage projects, as well as mining and drilling operations.

While the opportunity has always been there, Derrick Beetso said tribes have had trouble getting the funding to make them reality.

“A lot of times, tribes are limited with access to capital for projects in general,” said Beetso, the general counsel for the National Congress of American Indians. “Tribes are kind of left out of the process.”

Dante Desiderio, the executive director of the Native American Finance Officers Association, said the benefits of the loan-guarantee program are two-pronged.

“It makes it much easier for larger projects to get funded because it gives the guarantees to the banks that are willing to take a risk to underwrite these things for Indian Country,” Desiderio said. “The $2 billion is really significant for funding all sorts of energy projects and getting the banks comfortable with dealing with Indian Country for energy development.”

Beetso calls the start of the program “generally good news for tribes that are looking to develop their energy resources.”

“There are a lot of different needs in the tribal context that this loan guarantee program will help to address,” he said.

But Thomas said the program will not be a cure-all when it comes to energy development on tribal lands.

“There is plenty of money sloshing around in the system,” said Thomas, a Pascua Yaqui who served as the Interior Department’s deputy solicitor of Indian affairs. “The federal government has, by last count, close to 40 programs that can be used for financing energy projects on tribal lands.

“My experience has not been that it’s an access to capital problem,” she said. “My experience has been that it’s generally that the tribe has to recognize and have a commitment to go do a project.”

Desiderio disagreed, saying money has been one of the primary impediments to developing Indian energy.

“If it’s not one of the main barriers, it’s always in the conversation,” he said. Funding has “always been really helpful for Indian Country, but it’s not been enough. Just the size of this should have a major impact on Indian Country development.”

While Thomas does not expect immediate success, she is optimistic about the future of the tribal energy opportunities.

“For me the jury is out on where this is going to end up. The first year, you kind of have to wait and see,” Thomas said. “I’m hopeful. It’s always better to have more resources than less.”