PHOENIX – Can a miniature monsoon-storm machine save a super-small endangered snail? Bradley Poynter sure thinks so.

He leads the conservation team at the Phoenix Zoo, which recently faced a problem when trying to get certain diminutive mollusks to mate.

“Those land snails come out only when it rains,” he said. “They come out to eat, they reproduce and, as soon as the rain stops, they kinda cyst back up for the dryer weather.”

So Poynter and his team are creating a habitat where “rain” falls as needed. His plan isn’t too high-tech at the moment; he thinks he’ll just need a plastic lid, a drill and some hoses.

“You take the lid and you drill a hole in the plastic about every quarter inch or so … whatever area you want it to rain,” he said, “and then you just take an additional hose and just run it and create monsoon season! If we want to get really fancy, we can get a speaker system and a strobe light for thunder, but I think the rain will probably be enough to do it.”

The zoo’s snail-habitat prototype, which conservation technician Whitney Heuring just finished, doesn’t rain, but it looks just like a natural stream, complete with a streambed, running water, algae and plants.

“It really mimics that natural environment they would be living in,” Heuring said, gesturing to the water flowing over rocks into a shallow pond. From there, the water is filtered and reused.

Poynter and Heuring feel confident undertaking this new project because they’ve recently had some big successes.

They were members of the team that oversaw the first captive breeding of the Three Forks springsnail, a critically endangered species. They’re also successfully sustaining a colony of Huachuca springsnails, which never have before been studied in a lab.

The largest Huachuca springsnails grow only to be about 3 millimeters across. The Three Forks are bigger — at a whopping 4 millimeters. These two teeny species are found only in Arizona and are essential to the state’s stream ecosystems.

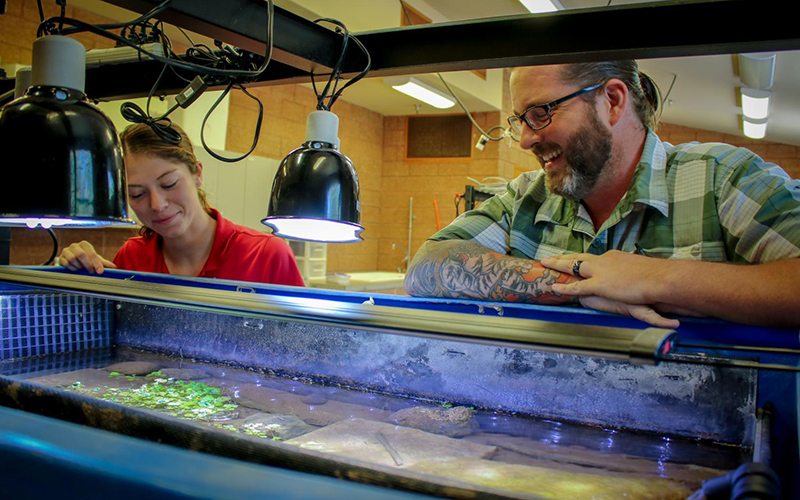

This conservation team doesn’t just focus on snails. The lab houses a number of endangered animals, and team members note key details each day that will help them save the creatures. (Photo by Claire Caulfield/KJZZ)

“They’re a food source for other invertebrates, and so if you start taking away a food source, then you start losing the predators and then the animals that eat those animals and the system kinda goes on,” Poynter said.

Additionally, these snails are like the canary in the coalmine of water contamination. Scientists pay close attention to their numbers because if the snails start dying, scientists know the water could be unsafe for cattle and humans downstream.

“Even though a snail might not seem important,” Heuring said, “it really does have its own special place, and so it’s important that we look at all the species and help all the species that are endangered.”

A big problem with studying these snails is their size. Even after spending all day working with them, the duo has a hard time finding even one Huachuca springsnail in the stream habitat.

“I hire much younger people with much better eyes,” Poynter joked while peering over the side of the plastic tub and gently lifting a leaf of an aquatic plant.

In a nearby tank, Three Forks springsnails cluster around algae formations. They’re just tiny dots on the glass, and even when you’re actively looking it’s hard to differentiate their shells from other debris.

The conservation team at the Phoenix Zoo has been trying to breed these springsnails for years.

“We’d get about 200 in and they live 12 to 18 months and then they would kind of just fizzle out,” he said.

But after trying and failing, and trying and failing, it appears a third time’s the charm.

“Well, either the third or the fourth,” Poynter said, laughing.

Thanks to a very expensive water filter, a specialized tank and help from the Arizona Game & Fish Department, Poynter and Heuring started seeing baby snails in May. In the painstaking daily count, their numbers held steady.

The streambed is packed with mud and plants, and nutrients can slowly bleed into the water through the siding. In the mini monsoon-storm machine, there will be room to house land snails and other invertebrates. (Photo by Claire Caulfield/KJZZ)

“We all got really excited about that,” he said.

Now that the team knows they’re not losing snails en masse, they’re expanding their efforts to the monsoon-storm machine, a contained ecosystem that mimics the natural world and will house multiple snail species at once. They’ll have the springsnails in the water and land snails and other invertebrates around the stream.

But instead of waiting months for rain like the rest of Arizona, these snails will get a storm on demand.

Poynter says this will be more efficient. He can house, breed and study multiple species with the same staff. But it’s going to take some time to get the machine up and running.

“It makes things difficult because, sometimes, you want to change a bunch of things at once, and if you do that and something works, you don’t know exactly what it is that caused that change,” he said. “It’s a big learning curve.”

And so the team is beginning the long process of trying and failing and trying and failing … until they get it right and can use the snails bred in the monsoon machine to repopulate ecosystems throughout the state.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

Connect with us on Facebook.