DENVER – Between growing populations and a changing climate, water sources in the West are only expected to get more crunched. Communities in some very dry states have had to get creative about where to get their water, sometimes purifying sewage into drinking water. More Western cities are beginning to get on board, too. But there’s a problem: The ick factor.

Paul Rozin has spent the last few decades testing what’s behind the disgust.

The University of Pennsylvania psychologist has asked people to drink a glass of water that had a sterilized cockroach dipped in it and to drink apple juice from a bedpan. In one experiment, he asked people if they would put on a sweater that Hitler had worn.

“And almost everybody says ‘No,'” Rozin said.

Rozin asked a few more questions: How about if he thoroughly cleaned the sweater? Or dyed it to look completely different? Or even unraveled the yarn and made it into a new one? Then would they put it on?

“And most people don’t want anything to do with it, even if you do all that stuff,” he said.

But there was something that could get people to reconsider: Mother Teresa. If Mother Teresa put on the sweater first, then some people would consider putting it on, too. In some way, her goodness would cancel out Hitler’s badness.

That study might sound like the stuff of academic ivory towers. But, says Brent Haddad, a water-resources economist at the University of California Santa Cruz, “it really caught the attention of the water industry.”

It was the late ’90s in California. Water engineers had come up with amazing ways to turn wastewater – all the stuff flowing down drains, sinks and toilets from homes – into clean, drinkable water. It was almost as if they’d found a way to turn trash into gold, Haddad says.

“The industry had reached this stopping point where it had identified technologies, methods and regulatory approaches that could provide safe recycled water to the public and the public would have nothing to do with it,” he said.

Haddad was attending a lot of water industry meetings. He says the engineers there were complaining “with some emotion in their voices” about an unexpected, seemingly insurmountable obstacle: human psychology.

One major problem was that people associated recycled water with excrement. Such slogans as “toilet to tap,” invented by opponents of water recycling, had made sure of that. Haddad reached out to Rozin to figure out how they could conquer people’s squeamishness.

“And he was the right man for the job,” Haddad said.

Together, Rozin and Haddad did a series of studies on people’s attitudes toward water. Here’s what they found.

“There’s two strategies. One is to tell them they’ve been drinking toilet water all their lives,” Rozin said. “Your toilet water goes down to the ocean, so does everybody else’s toilet water, and then it’s coming back in rain.”

And what, he says, do you think river water is? A lot of it is just treated sewage from towns upstream.

But that tactic – the whole-world-is-gross tactic – doesn’t work for everyone. Others need help ignoring the water’s gross past. We do this mental trick all the time, Haddad says, such as when we sleep in hotel rooms.

“There’s a really good chance that that pillow was in places and in contact and having experiences that would just be appalling to the next person who comes to the room,” he said.

But in our heads, we tell ourselves that the cleaning crew came through and now everything is clean, he said, “and we’re perfectly fine sleeping on that bed. We frame out any history of that hotel room.”

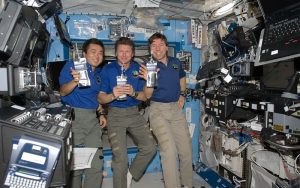

Since 2009, astronauts aboard the International Space Station have been drinking water recycled directly from their sweat, breath and urine. “Direct potable reuse,” as the closed-loop system is called, is used in just a few places on Earth, including Big Spring, Texas, and Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo courtesy NASA Johnson/Flickr)

Explaining to people exactly how water gets cleaned can have a similar effect – especially if you emphasize the fact that treated wastewater often goes back into a natural place, such as an aquifer or a stream, and mixes with other water there before getting pulled back out and retreated again to drinking quality. The process is called “indirect potable reuse,” and it’s already used by some cities across the U.S. — although the Environmental Protection Agency says only about 7 percent of the wastewater effluent produced each day in the U.S. is reused.

Haddad says that extra step in nature isn’t necessary. Existing technology can make wastewater safe and drinkable straightaway, just as it does on the International Space Station, in Windhoek, Namibia, and in Big Spring, Texas. In fact, he says, treated wastewater often is cleaner than the water it intermingles with in aquifers and streams. But the idea of the water spending time in nature helps people ignore its less appealing past, just as they can ignore the hotel room’s past.

“People can easily say, ‘Oh, well I’m getting the fresh stuff,'” he said.

Another thing that helps is to show people that it’s safe by pointing to other people who drink purified wastewater, including astronauts, whose drinking water comes from their own breath, sweat and urine.

“They’re game,” Haddad said. “Otherwise they don’t go up there.”

Urgent need can speed up the process, as in the case of Windhoek, Namibia and Big Spring, Texas. Both experienced severe droughts that led local authorities to declare water crises. In 2011, Texas experienced the worst drought in the state’s history. The situation was so dire, Haddad says, Big Spring residents considered shutting down the city. Instead, they turned to recycling their wastewater.

Austa Parker, a water-reuse technologist with the environmental engineering firm Carollo Engineers, wants residents of the West to embrace recycled water – indirect or direct – before they hit such a drastic turning point.

“We need to be doing this. If we keep seeing decreasing water supplies over time and we keep seeing population increases in certain areas then we’re going to need more water eventually,” she said.

Parker works with the WateReuse Association of Colorado, a trade organization focused on water recycling. The group teamed up with utility Denver Water to set up a demonstration space where Parker spent a few months showing people the water purification process and getting them to taste water samples (which she refers to simply as “purified water”).

Declaration Brewing Co. in Denver makes the Centurion Pilsner, which is brewed with recycled wastewater. (Photo courtesy Declaration Brewing Co.)

When the demo wrapped up, Parker took the remaining purified water and brought it to Declaration Brewing Co. in Denver. Although there might not be a Mother Teresa antidote for recycled water, beer comes pretty close.

Centurion Pilsner, made with recycled water, already is on tap there.

“It’s a very crispy, refreshing, clean, nice, dry finish. Exactly what you’d expect out of a very classic example of an American Pilsner,” brewery founder Mike Blandford said as he sipped a glass of Centurion.

Blandford and his colleagues at Declaration Brewing want to help prepare people for water shortages before things get urgent, as they did in Big Spring. Easing them in gently with a recycled Pilsner just might do the trick.

“Water is water. You get the right elements in it and it’s fine,” he said.

Spokesmen with Denver Water say the city could be drinking reclaimed water in about 40 years. The nearby municipalities of Aurora and Parker already recycle wastewater into drinking water indirectly. The nearby town of Castle Rock is currently designing upgrades to its water-treatment plant that should allow for indirect potable reuse by 2020.

Mark Marlowe, director of Castle Rock Water, says the town currently gets about 80 percent of its water from groundwater in the Denver Basin.

“We’re depleting it faster than it’s being replenished,” he said.

The town started looking into renewable options about a decade ago, spurred by drought and the fact it has fewer water rights than Denver and other older municipalities.

“The upgrades that we are designing to our water plan are the same upgrades that would be needed if we were going to do direct potable reuse,” Marlowe said.

He points out that with indirect reuse, the town could risk losing a lot of its water during a drought by including that extra step of discharging the water to a creek that’s in the process of drying up.

“Ultimately, we do want to be able to do direct potable reuse,” says Marlowe. “If you have a serious drought, it’s much more reliable.”

This story is part of a collaborative series from the Colorado River Reporting Project at KUNC, supported by a Walton Family Foundation grant, the Mountain West News Bureau, and Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between public radio and TV stations in the West, supported by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.