Flags from of the hundreds of Native American tribes in the U.S. The agencies that deal with tribes – the bureaus of Indian Affairs and Indian Education and the Indian Health Services – remain on a GAO “high-risk” list for management shortcomings. (Photo by Pioneer Library System/Creative Commons)

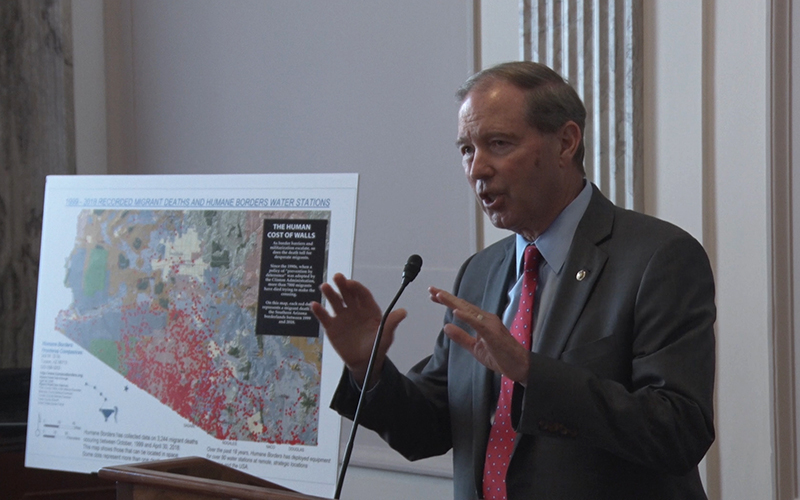

Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico, shown here in a file photo, was skeptical of officials’ claims that agencies overseeing Indian affairs are making real management improvements, asking if they’re not just “checking boxes” to look like progress. (Photo by Pat Poblete/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Federal agencies that oversee Indian affairs are making progress toward fixing management shortcomings that landed them on a list of “high-risk” agencies, but not enough progress to satisfy some senators.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education and Indian Health Services have for years been on the Government Accountability Office’s high-risk list of federal programs that are vulnerable to mismanagement.

Officials from those agencies told the Senate Indian Affairs Committee Wednesday that they are now meeting, or at least beginning to meet, GAO recommendations for improved operations. But senators, and other witnesses, said the agencies still have a way to go.

“Based on some recent information from the agencies, there has been some progress from the Bureau of Indian Education and the Indian Health Services,” said Sen. John Hoeven, R-North Dakota, the committee chairman. “Over the past year, we have seen very little progress in implementing Indian energy.”

Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico, questioned whether officials are really changing the culture of their agencies or merely “checking off boxes.”

“The federal government has trusted treaty obligations to provide vital services to American Indian and Alaska Native tribes,” said Udall, the ranking Democrat on the committee. “GAO’s review of Indian programs ensure our government is living up to and respecting those obligations … especially those on the high-risk list.”

Frank Rusco, director of natural resources and environment at the GAO, said there has been progress. He pointed to the BIA – which has met frequently with the committee over last nine months – noting that the agency has closed nearly a third of the GAO’s 14 recommendations for improvement.

“We identified most, if not all, progress meeting this criteria,” Rusco said. “Still, additional progress is required in all areas, particularly in the areas of leadership, commitment and the capacity and resources needed to identify and address root causes.”

Rusco said one problem has been a high rate of turnover in BIA leadership positions. The issue of high rates of job vacancies was echoed by many of the other speakers.

While BIE Director Tony Dearman said his agency has closed seven of its 13 recommendations to improve school management and is making progress on the rest, Hoeven chided the agency for a large number of unfilled positions.

Dearman said that “location and isolation of our positions” has posed a problem for recruiting.

“We’re really working with the department to move some of those positions out of D.C., because we’ve heard from tribal leadership that we need those acquisitions,” Dearman said. “We’re really anticipating by relocating the … positions, we’re going to recruit and be able to hire some.”

High numbers of job vacancies at IHS has also led to long patient wait times, lack of organizational capacity, and lack of effective monitoring of health care centers and hospitals across the system, said Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, the acting director of the agency.

“Reducing wait times continues to be a priority for the agency,” said Weahkee, in testimony prepared for the hearing. “The OQ (Office of Quality) will ensure that quality is integrated into all agency programs in a collaborative and organized manner.”

Udall said fulfilling the GAO recommendations is not enough, saying he wants to see evidence of a culture shift and institutional change to remove the high-risk designation.

“Year after year, tribal communities report gaps in federal programs, and in response our federal partners point to workforce turnover and lack of resources as the source of programs’ ineffectiveness,” he said. “We must do better.”