CONGRESS — Not so long ago, teachers at Congress Elementary School had to start downloading a video the night before showing it in class.

The school was hobbled by low internet broadband speed, or bandwidth. In densely populated

areas, such as Phoenix and Tucson, bandwidth is high, so online content loads as swiftly as cars on a highway. Outside metro areas, going online is like a traffic jam on a one-lane dirt road.

In Congress, an old mining town turned farming community 50 miles southwest of Prescott, students once trailed city folks in online educational resources. But in recent years, educators in Yavapai County cobbled together state and federal funds to upgrade their broadband connection, and this year won an $1.8 million grant that will bring it up to standard.

The new high-speed broadband won’t just benefit classrooms. Libraries, homes and entire towns can take advantage of the connection – which educators say has been a long time coming. Overall, Arizona ranks 29th among the 50 states in connectivity.

Teachers fed up

First-grade teacher Caitlin Hunt came to Congress a few years ago after working at a school where she could stream music during work, play educational YouTube videos and watch Netflix with her students. She didn’t know her bandwidth-hungry habits would turn into a story her principal and technology specialist often retell.

Hunt inadvertently prevented other classrooms from accessing the internet because the school’s limited bandwidth wouldn’t allow room for anyone else to process downloads.

Principal Stephanie Miller said the teacher of Grades 6 through 8 would call and say, “We can’t get into our (digital) math program! Because the bandwidth wasn’t there.”

Another challenge came when state standardized testing went digital in 2015. Although Congress Elementary had an internet connection, it was so weak that up until last year, students took tests using paper and pencil, just in case the system failed.

The first step toward better connectivity came in 2014, when Suzanne Phillips Sims, Congress Elementary School’s technology specialist, stumbled upon a small microwave internet company that was installing equipment atop the town’s water towers. Microwave connections utilize transmission towers, which must be directly in the line of sight of a receiving antenna. Sims asked the technician installing the equipment, Wayne Markis, whether he’d provide internet at the school for an introductory rate.

The school’s relationship with AZ Airnet was born. Congress Elementary saw a much better connection, and the teachers were pleased with the round-the-clock service.

“We adore him,” Miller said of Markis, who owns AZ Airnet. “It’s finding a quality person that will provide that individualized service.”

With AZ Airnet’s help, the school made big strides, but the connection was still slow and there were problems, like maintenance calls in the middle of the night.

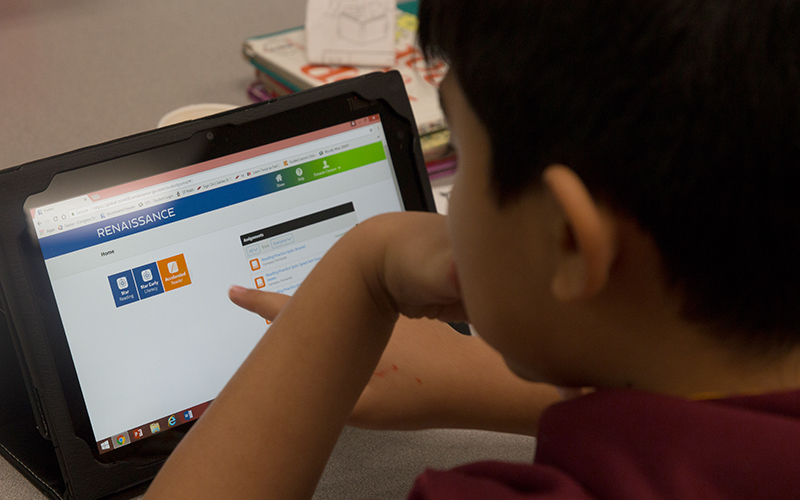

First-grade students at Congress Elementary School use iPads as part of class instruction. (Photo by Faith Miller/Cronkite News)

Connecting a community

New funding will allow Congress Elementary, as well as 60 other schools and libraries throughout Yavapai County, to access to a new fiber-optic connection that will provide faster, more reliable internet.

The money comes from $1.8 million federal grant as well as $400,000 from the state, through a funding initiative that began last year.

The Arizona Broadband for Education Initiative grew out of a partnership between the state Department of Education, the Arizona Corporation Commission and a nonprofit, Education SuperHighway. It designates $11 million from the state budget and Universal Service Fund to help schools and libraries improve access to internet. Matching funds from the federal Schools and Libraries Program, commonly known as E-rate, have amounted to more than $100 million for the state.

Rather than applying as individual entities, which would have made it more difficult to obtain funding, dozens of county schools and libraries banded together to submit an application for the grant. The money will pay an internet provider to install fiber optics in the county, improving access to homes, businesses and public safety agencies.

“We figured out that there’s bigger power in numbers,” said Stan Goligoski, executive director of the county’s education service agency. “We’re one entity rather than just a little school trying to do things for themselves.”

Goligoski said internet providers jumped on the chance to serve the area when they heard the government was paying to build the fiber-optic line. The free infrastructure also meant the winning provider, Cable One, could keep prices low for internet users.

“They’re saying, ‘Well holy cow, we’ve got an entity that’s going to pay for this build and now we can run this fiber into Peoples Valley, Congress – it’s paid for?'” Goligoski said. “With that, they were able to drive their price significantly down.”

Schools left behind

Arizona is ranked the 29th most-connected state by research group Broadband Now.

“We have a lot of underserved schools particularly in rural areas that don’t have the sort of access to technology and broadband that schools in metro areas such as Flagstaff, Tucson and Phoenix do,” said Stefan Swiat, a spokesman for the Department of Education. “What we’d like to do is give them every educational opportunity that students in metro areas have.”

Congress at least has a microwave connection, but other schools in Yavapai County and elsewhere in the state have even less access. Education SuperHighway identifies 107 school districts, including Congress, that still need a fiber-optic connection, and 48 school districts that still need bandwidth upgrades. Those 48 districts have not met the nonprofit’s minimum standard of 100 kbps of bandwidth per student.

The schools that need bandwidth upgrades or lack a fiber-optic connection fall under Category 1 of the E-rate funding program. These schools need “the big expensive stuff,” Swiat said.

“That’s where you have to actually dig in the ground and connect people by miles and miles of fiber,” he said.

“The cost of doing that Cat 1 work can be so prohibitive that districts don’t undertake it,” added Sophia Green-Robinson, state engagement manager for Education SuperHighway. “So having this match opportunity in some instances would mean that there’s no cost at all to the district to do the construction.”

Schools that fall under Category 2 may not need fiber optics installed, but do report insufficient Wi-Fi. This category includes 185 districts around the state.

“That’s when you have sort of in-house hardware that is associated with hooking up networks of computers,” Swiat said, “and it’s a lot quicker to get that out to schools that request those funds because it’s obviously not as expensive and it’s easier to transport.”

Disconnected pockets

In Yavapai County, homes in rural areas have limited access to internet, largely because internet providers are unwilling to run fiber optics into low-population areas where it’s harder to make returns on their investment.

“There’s not enough customers here,” said Phillips Sims, the technology specialist at Congress Elementary School. “That’s why CenturyLink’s never done it. I mean, CenturyLink had the line. It’s all along the highway, but (they said), ‘We’re not coming into Congress. We’re not going under the railroad tracks and coming in here because it’s never going to pay.'”

The Navajo Reservation faces similar issues, said Brent Nelson, systems and programming manager for the Navajo Department of Education. On top of that, the tribe has been unable to obtain E-rate funding because the Navajo Nation is a sovereign government entity, Nelson said.

“The problem with that is that E-rate only supports education institutions. So you have to be a school, you have to be recognized as a education entity for you to apply for E-rate,” Nelson said. “So really, the buck stops there, for us to address broadband for education for our schools.”

Internal tribal regulations, Nelson said, can also bog down the process of building infrastructure for a fiber-optic connection.

“The requirements are pretty stringent for anybody that wants to put in infrastructure,” he said. “By the time you get the agreements, the i’s dotted, t’s crossed kind of deal, the application has already come to a close.”

Nelson said the Navajo government is working to identify other ways to improve access for underserved areas. One solution could be tapping broadband resources in New Mexico, working with schools across state borders.

Fifth-grade teacher Cheryl Middleton helps an 11-year-old with math. (Photo by Faith Miller/Cronkite News)

Ripple effect on learning

Congress Elementary’s internet capability remains less than half of what Education SuperHighway recommends for it, but the planned fiber-optic connection should improve download speed at school – and help the students learn at home.

Right now, teachers have to be careful about assigning homework that requires students to go online, although Congress Elementary often sends laptops that have pre-downloaded material home with students. Many families can’t afford to pay for the microwave connection provided by AZ Airnet, the only way people in Congress can currently connect to internet.

“Our students do not go home with access to internet,” said Miller, principal of Congress Elementary School. “They go home with access to phones, which have internet. That’s if they’re fortunate enough to be able to afford those.”

The fiber-optic connection Cable One is installing to service Yavapai County schools – paid for by the E-rate funding – could make it easier and more affordable for students’ families to have internet at home.

At school, getting online no longer is a problem.

“I use technology every day in class,” Hunt said this spring. “This week, we’re learning about ‘ea’ and ‘ee’ sounds. We’re doing videos, we’re doing dances, just different learning games on my smartboard, and I wouldn’t be able to do that without the bandwidth because of the processing time.”

Internet access also gives teachers more flexibility, allowing for individualized instruction. Teachers at Congress Elementary use apps and computer programs that let students learn at their own pace.

“If this student really needs practice on their short vowel sounds, whereas this student is excelling and they can do long vowels, I can do individualized learning and I can send those to their tablets,” Hunt said. She added that the math program she used “goes at their level and their pace, so they can’t move on until they have a skill mastered.”

With the upgrade to fiber optics, Congress will gain more of that flexibility, as well as better connectivity. Miller brought up a project through NASA that one classroom was implementing, in which students used “interactive television” to connect with a classroom in urban Argentina. Together, the students learned about what it would be like to survive the first two weeks on Mars.

“Now these type of experiences are going to be that much more secure,” Miller said. “Because there were moments with Argentina that the internet did, it was hard … you had to find certain times during the day for instruction that wouldn’t impact other instruction.”

The project also will allow the school to upgrade from analog phones, providing more dependable communication and improving the fire alarm system.

Milan Eaton, state E-rate director for the Department of Education, said the state will continue working with Education SuperHighway on the broadband initiative, regardless of whether state funding is available in the future. Even without money from the state, he said, E-rate funds would still save rural schools 90 percent of the cost of upgrades.