Puerto Rico school turns adversity into strength after Hurricane Maria

By Aydali Campa/ Cronkite Borderlands Project |

CIDRA, Puerto Rico – Hurricane Maria took Principal Debra Angie Hernandez’s father, but she was determined it wouldn’t take her school.

Just days after the hurricane struck, Hernandez and teachers such as Melba Passapera and parents such as Hilda Marina Santos sprang into action to make sure the Luis Munoz Iglesias K-12 school would not become another of the storm’s victims.

The specialized bilingual school had just been freshly painted a month before the violent winds of Maria arrived on Sept. 20, 2017. It was quiet in the days that followed: The roads were too dangerous to navigate, and the Department of Education hadn’t greenlighted anyone to step onto school campuses.

Six days after the hurricane struck the island, Passapera turned on the radio to hear an announcement from the department calling on school staffs to visit their campuses to assess damage.

The image of what they found – a field of fallen trees, mounds of mud, flooded classrooms and downed electrical wires – was still seared in Passapera’s memory six months later.

“It was really a mess,” she recalled.

The teachers, the principal and the parents slowly began to rebuild what once was a vibrant turquoise building with tall greenery that decorated every nook of the campus that is so much a part of Cidra, known on the island as the City of Eternal Spring.

Week after week, parents and others in the community joined in the effort. As soon as the roads were safer to navigate, parents such as Santos helped clear the disaster. They used chainsaws to cut through collapsed trees, cleaned classrooms and installed six water tanks to ensure the children had potable water. With their help, the school is nearly restored.

Hernandez, the principal, said she wasn’t surprised at the staff and community effort. She said the school is one in which “all the community is involved in the process of maintenance,” a school-community partnership that dates to 1999. Every month, members of the community clean, cut grass or paint to keep the school in top shape, she said.

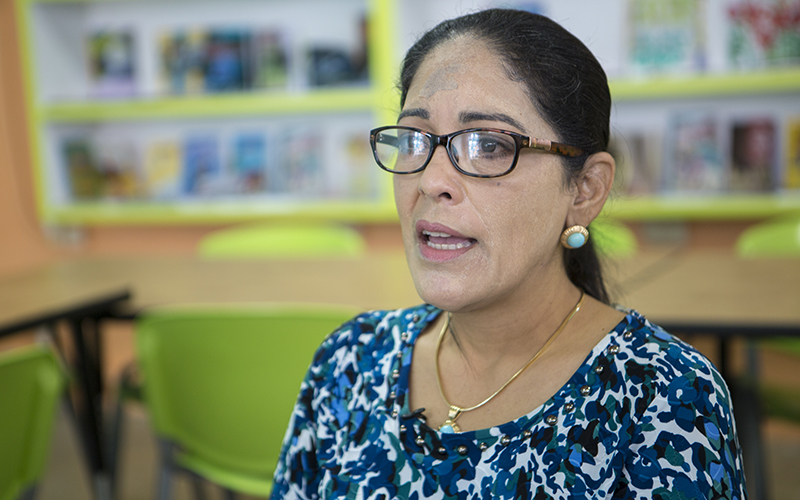

Debra Angie Hernandez, principal of specialized bilingual school Luis Munoz Iglesias, said the community is heavily involved in maintaining the school in Cidra, Puerto Rico. (Photo by Johanna Huckeba/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

So it was natural for the community to come together to rebuild the school after the hurricane.

“We had to do it by ourselves with the help of the students, parents, teachers,” Hernandez said. “We had to do it because we wanted to start.”

But Hernandez’s pride in the community effort was tempered by the loss of her father.

“Due to the lack of electricity, he couldn’t breathe, and I lost him it,” Hernandez said.

Her father needed medical care that required electrical power to treat his asthma and pulmonary emphysema. Like millions on the island, her home lost electricity. The generator that powered her father’s nebulizer broke, and he died shortly before the repairman arrived.

“But the rest of the things I was lucky because my house doesn’t suffer that much,” she said, wiping her tears.

She found support and comfort from the tight-knit school community, and she said she admires her teachers’ efforts in helping students cope with their individual struggles after Maria.

School success at Luis Munoz Iglesias K-12 is welcome in a Puerto Rico educational system that was suffering budgetary problems and steep drops in enrollment even before the hurricane. In April, the Puerto Rico Department of Education announced the closure of 283 public schools following an exodus of about 40,000 students to the U.S. mainland since May of last year.

While Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Education Julia Keleher has faced harsh criticism for the closures, she believes it necessary to alleviate the financial crisis the island has been facing for years now, especially amidst its recovery from Hurricane Maria.

“Our children deserve the best education we are capable of giving them taking into account the fiscal reality of Puerto Rico,” Keleher said in a statement issued in Spanish in April. “Therefore, we are working hard to develop a budget that will allow us to focus resources on student needs and improve the quality of teaching.”

The school closures were announced a week after Gov. Ricardo Rosello signed into law the implementation of private school vouchers and “allegiance schools,” similar to charter schools on the U.S. mainland. The new program drew criticism from the teachers’ union.

“The educational reform that is being presented at this moment does not redound to the interests of Puerto Rican public education,” Aida Diaz, president of the Puerto Rico Teachers Association, said in March.

The sweeping public-school changes come at a difficult time, as students and faculty are still recovering from the hurricane, Diaz said.

Passapera, for example, just re-acquired electricity at her home in April, seven months after the hurricane.

By the end of April, 53,000 households still did not have electricity, making Hurricane Maria the cause of the second-longest blackout in world history and the longest in U.S. history, according to economic research firm Rhodium Group.

Many students, including graduating seniors such as Omaris Rosario Luquis, 17, still do not have electricity in their homes as they prepare to transition into college. They missed out on two months of college preparation.

Still, she considers herself one of the “blessed” ones in her school. Her home escaped severe damage. “Gracias al Senor” – thanks to the Lord – she said.

Some students were not as fortunate.

Kenneth González Cruz, 13, lost his home. His school uniform was one of the few belongings his mother could salvage before the hurricane demolished the house.

Eight students and one teacher lost their homes to the Category 5 hurricane.

Passapera’s own experience as well as the ordeals that her students and Principal Hernandez experienced sparked a desire in her to go beyond physically repairing the school.

“So we were thinking our problem was, ‘Where are these kids going to do their homework?'” Passapera said. “‘Where are they going to for their free hours?'”

Related Story

That is when Puertas Abiertas – “open doors” – started to take shape.

Passapera was inspired by a piece written by an Arizona State University communications professor Manuel Aviles-Santiago for Puerto Rico’s largest newspaper, El Nuevo Dia. In it, he described how immediately after the hurricane, he started teaching his class in the dark in solidarity with the crisis Puerto Ricans were facing. She admired his initiative.

“We didn’t know how long we were going to be in the dark, and education is the only way that I thought at that point we’re going to be able to just start over again,” Passapera said.

With the help of her family, which was in Arizona at the time, she contacted Aviles-Santiago and explained her idea of Puertas Abiertas in hopes that he would help make her vision a reality.

She pitched the idea to Hernandez, who provided a large storage room in the upstairs corner of the building.

Passapera bought paint as soon as the local paint store reopened in November.

Teacher Elymary Dones and parents jumped into the development, too. Santos said she couldn’t pass on the opportunity to help create something that would allow her daughter Marina Loraine to cope with her emotions after Maria.

“For me, school is my children’s second home,” Santos said.

Her family was involved in every step of the recovery, as well as the creation of Puertas Abiertas.

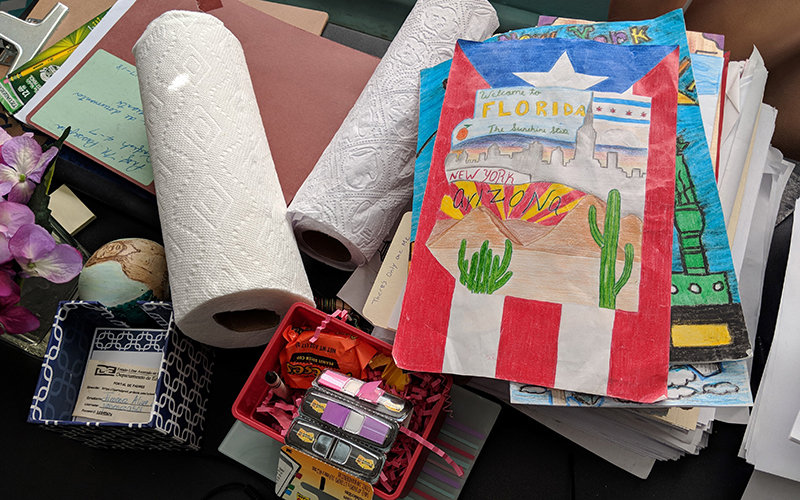

In January, the school received a dozen boxes full of school supplies, including backpacks, books and even board games following Aviles-Santiago outreach in Arizona and other states.

Parents and even students built the program through small monetary donations and physical labor.

By February, Puertas Abiertas was up and running.

Before she created the program, Passapera made do with the limited resources available when the school reopened in mid-November, holding class outside and teaching arts and crafts with debris from the hurricane such as small branches that were scattered around the campus.

Now, her idea, Puertas Abiertas, is an integral part of the school’s curriculum at every grade level.

Hernandez describes the program as an “emotional shelter” because students can forget about their personal struggles while engaging in a safe space.

Students at every grade level visit the former storage room and engage in activities ranging from yoga and readings to arts and crafts and reflective writing.

Jacque Marlin, a life and wellness coach, often visits the space as a guest speaker.

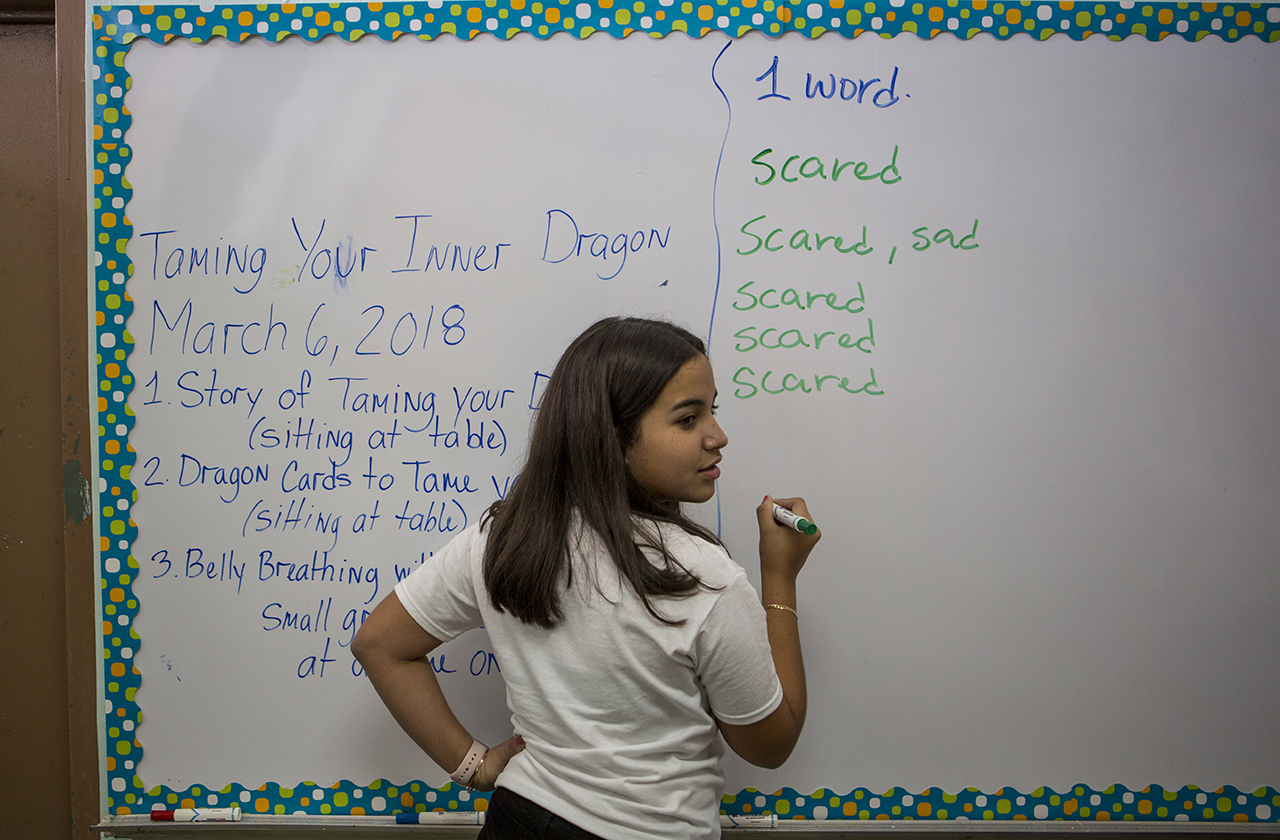

In March, Marlin lead Passapera’s fourth-grade class in meditation at Puertas Abiertas. She then recited from her book, a work in progress about how to emotionally “tame the dragon” that was Hurricane Maria.

Students at specialized bilingual school Luis Munoz Iglesias in Cidra, Puerto Rico share words to describe their experience of Hurricane Maria as part of a “Puertas Abiertas” (Open Doors) lesson. (Photo by Johanna Huckeba/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

“She could not control the storm, but she could control how she reacts,” Marlin read.

Passapera said she has seen improvement in her students’ ability to focus and work independently since she started implementing creative and physical activities for the students.

Teachers constantly asked each student since their first day back if they had water, electricity and shelter, she said.

“I don’t feel nervous anymore,” said student Marina Loraine Santos, who was shaken by the impact the hurricane had on her home.

Other students attribute their academic and emotional recovery to simply the school’s outreach.

“The teachers who’ve been in my life have worried about my personal life, my personal growth,” said Rosario, a 12th-grade student who’s been attending the school since kindergarten.

Passapera felt a program such as Puertas Abiertas was essential to show her students that they were not alone in their recoveries from Hurricane Maria. The faculty understood the emotional toll of the natural disaster, as they faced the same ordeals their students faced.

“We are teachers who go the extra mile,” said Passapera, who earns $31,000 annually, about $7,000 below the average beginning salary for teachers on the mainland United States.

She has 24 years of teaching experience, two bachelor’s degrees, a master’s degree and a bilingual teaching certification.

Her goal is for students to learn to be productive members of their community and their nation, especially in times of need, more lessons driven home by Hurricane Maria.

Cronkite Borderlands Project is a multimedia reporting program in which students cover human rights, immigration and border issues in the U.S. and abroad in both English and Spanish.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]