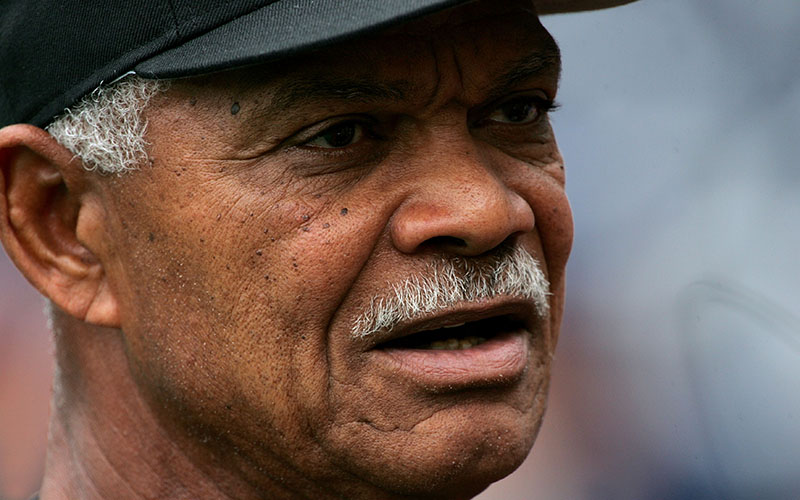

Felipe Alou’s greatest legacy is the amount of Dominican players now in Major League Baseball. He was the first player born and raised in the Dominican Republic to play in the majors. (Photo by Stephen Dunn/Getty Images)

Felipe Alou, right, was convinced by author Peter Kerasotis to write a book about his life. Alou is a big reason so many Dominican players are in the majors. (Photo by Katie Woo/Cronkite News)

SCOTTSDALE – Felipe Alou’s legacy on the baseball diamond extends far beyond what he accomplished as a player or manager.

Just look around any Major League Baseball stadium.

Six decades have passed since Alou made his major league debut with the San Francisco Giants. But he didn’t just make his debut that day. He made history. Often dubbed the “Jackie Robinson of the Dominican Republic,” Alou became the first-ever player born and raised in that nation to play in the majors. He debuted on June 8, 1958.

“it’s motivating,” Diamondbacks shortstop Ketel Marte said. “He’s one of the people you have to follow. He can teach us many things.”

Marte is one of 77 Domincan players to start the 2018 season on a major league roster and the country contributes the most players to the league born outside of the United States.

Alou, who spends spring training in the Valley as a special assistant with the San Francisco Giants, inspired not just Domincans but many Latin players. When he debuted in ‘58, the percentage of Latinos who had played at least one game in the major leagues was just 5.2. In 2016, they represented more than a quarter of the league (27.4 percent).

The Dominican Republic has introduced decorated Hall of Famers and beloved franchise legacies ranging from Juan Marichal to Pedro Martinez to David Ortiz.

Alou’s journey to the big leagues from his home in Bajos de Haina, San Cristóbal, mirrors the path that hundreds of his successors have followed in pursuit of a new life in a new country, while playing the same game.

“I believe I was a good player, I was a decent manager, but I have been exposed to so much other stuff because of baseball,” Alou said.

His story inspired others. Without Alou, the country’s trailblazer, it could have all been lost.

The rise of Dominican players in the major leagues stems from an economic deficit, combined with the country’s own love of the game. Nearly four of every 10 people in the Dominican Republic live in poverty. Baseball is a widely popular sport there, and the country even has its own baseball league, the Dominican Winter Baseball League. The opportunity to escape economic challenges while playing professional ball is seen as a ticket to fortune.

It’s the American dream.

After finishing his rookie season with San Francisco, Alou went on to play a 17-year career in the big leagues. His first six years were spent with the Giants, where he played alongside Marichal, Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda. His brothers, Mateo Alou and Jesus Alou, were also in the Giants organization and in 1963, the brothers formed an all-Alou outfield during a professional game. The feat hasn’t occurred in the major leagues since.

Throughout his career, Alou also spent time with the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, the Oakland Athletics, the New York Yankees, the Montreal Expos and the Milwaukee Brewers before retiring as a player in 1974. He returned to the Expos organization in 1976 as an instructor, but the accidental death of his oldest son resulted in Alou stepping away from the team for nearly a year.

During the 16 years, Alou served as a minor league manager for the Expos and spent his winters back in the Dominican Republic, managing his former baseball team. In 1992, he was named the manager of the Expos, becoming the first Dominican to ever manage in the major leagues. He managed the Expos for nine years, served as a bench coach for the Detroit Tigers in 2002 and replaced Dusty Baker as the Giants manager in 2003 for four season. He also managed his son, Moises Alou, in both Montreal and San Francisco.

Peter Kerasotis, an author and well-established journalist, took a fascination to Alou’s story. He has spent the last five years conversing with Alou and is the co-author of “Alou: My Baseball Journey” which was published last April.

“I really believe his life story needed to be told,” Kerasotis said. “It is an important part of baseball history and his country’s history.

“He is their Jackie Robinson, he paved the way for everybody. Now that country produces more players than any other country outside of the United States.”

Kerasotis, who lives in Florida, had tried unsuccessfully to convince Alou to writing the novel. It took persuasion, persistence and some help from Giants current manager Bruce Bochy to finally convince him.

“I told him, ‘Felipe, your story shouldn’t die with you,’ ” Kerasotis said. “When Ernie Banks died, I wrote (Alou) a letter and said, ‘I’m not trying to be morbid here but this is your generation. If you go, all of that goes with you.’ ”

Eventually, Alou agreed.

The book weaves through the tales of Alou’s early life in the Dominican Republic and the impact war had on his family. It delves deep into Alou’s baseball career, both as a professional player and manager, and the impact it had on his family immediately and his country remotely. It tells stories Alou had never spoken of and shows history in the way that statistics cannot.

“This is not another baseball book,” he said. “This book contains things from where we were born, war, my parents, my brothers and sisters, until practically this day.

“I call it a 95 percent complete book. I believe there are some things in a man or woman’s life that we will never share. Those are the things that are not in the book, but I tried to be very exact.”

To Kerasotis, it was a story that needed to be told. The opportunity to listen to Alou is just as profound, even with players nearly 60 years younger than him. Alou, who still serves in the Giants organization as a special assistant to general manager Larry Baer, is still involved with the Giants’ major league partnership in the Dominican Republic. Each major league team has an academy in the Dominican Republic dedicated to to promoting and building promising prospects from the country. The Giants facility is located in Boca Chica. It’s name? The Felipe Alou Baseball Academy.

“He’s a mentor,” Kerasotis said. “He goes over to the minor league complex a lot. Last year I was with him and when they came out of the locker room, they all circled around him. Not just the Dominican players but the other Latino players as well and he would hold court like Yoda from Star Wars.

“It’s been very interesting to see his stature amongst his peers, the young guys coming up, and the media that covered him as a manager.” Kerasotis added. “He has an aura, a charisma and a presence about him that attracts people.”

Giants pitcher Johnny Cueto, a Dominican native as well, is one of those people.

“I always talk to him when he’s here,” said Cueto, through interpreter Erwin Higueros. “He’s always positive, he’s always talking about the young arms that we have. He was a great manager and trusted all of his players.”

Alou is 82 now, but according to Kerasotis, Alou still has one of the best memories Kerasotis has ever witnessed. He maintains his relationships both on the diamond and off, and still keeps a witty sense of humor. Finally his story is out on paper, with no chance of being lost.

“I have been a complete baseball person,” Alou said. “I had managed in the minor leagues, I did some scouting for the Braves. I was instrumental in other players who didn’t make it to the big leagues. When I came back to the Giants, I felt like I was realized.

“My children started to tell me, ‘You have a story to tell. You have to write a book.’ ”

So he did. “Alou: My Baseball Journey,” is co-authored by Kerasotis and published by University of Nebraska Press.

As the Giants commemorate their 60th anniversary in San Francisco throughout the 2018 season, there is little doubt that Alou will be celebrated accordingly. He, and his story, should be celebrated throughout baseball, too.

Follow us on Twitter.