WASHINGTON – The charge from National Native American Veterans Memorial officials was daunting: Design a memorial that honors the contributions of every tribe to every war fought for the U.S.

“There are 565 native tribes across the country, and to put that into one statue was a little difficult,” said Enoch Kelly Haney, one of more than 100 designers who accepted the challenge.

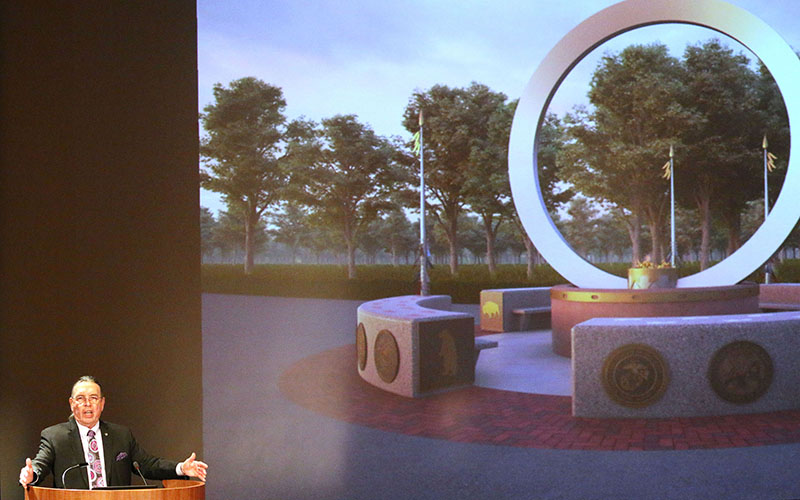

Haney’s entry was one of five unveiled last week as finalists for the memorial, which will be located on the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian, in the shadow of the Capitol.

The five projects range from the more traditional – statues of Native Americans wearing various U.S. military uniforms, some with tribal headdress – to more abstract designs, rich in symbolism and cultural meaning.

“The designs are just things we as Native people understand, we just do what we do,” Haney said Wednesday, as the finalists were presented.

The memorial has been more than 20 years in the making. First authorized by Congress in 1994, it was to be built within the walls of the museum, with all funding to come from the National Congress of American Indians.

But the project didn’t pick up steam until 2013, when Congress authorized the museum to start accepting contributions along with the national Indian congress, and decreed that the memorial be placed outside the museum.

Native Americans have served in all American wars. In World War II, more than 10 percent of the total Native population in the U.S joined the military, even though they were still denied basic civil rights at home.

“We’re just a patriotic group of people,” said Haney, a Seminole who served in the Oklahoma National Guard at a time when he was denied service in hotels and restaurants near his training facilities, “because of the color of my skin.”

“It’s just the idea of sacrificing regardless of the fact the government was not treating you well,” said Stefanie Rocknak, one of the design finalists.

One possible reason for their service could be the amount of respect Native Americans give to those joining the military and those coming back from war, the designers said.

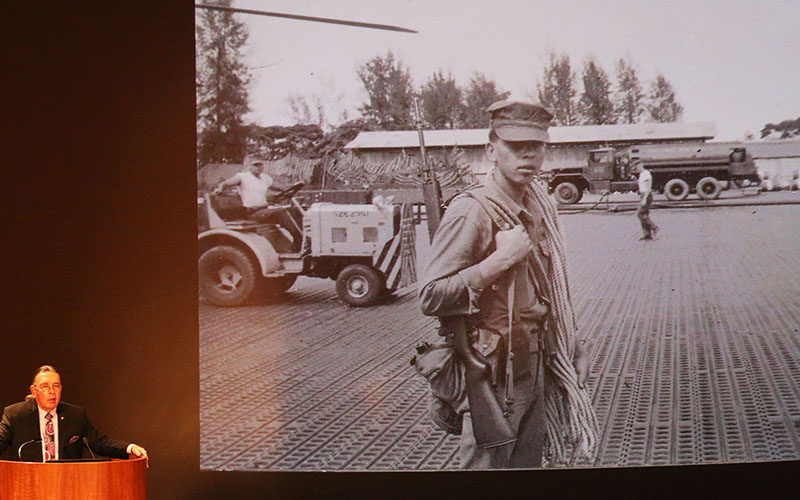

“When I came home from Vietnam, they did an honor dance for me,” said Harvey Pratt, a Cheyenne/Arapaho, and Marine veteran.

“They gave me a song and they made me feel better, they made me feel like someone. That was better than some other guys that were called baby killers,” said Pratt, whose memorial design was among the five finalists.

Pratt was one of 42,000 Native Americans who served during the Vietnam War. Despite support from their communities, they faced dire challenges when they came home, Haney said.

“My two brothers went and all the young men from my church community, they all went. They all came back, but they all died,” Haney said, referring to mental wounds they brought home from the war.

Pratt sees the memorial as a potential place for healing the emotional wounds that all wars create, mirroring the way the ceremonies his community performed on his return from Vietnam helped him heal.

“We want something they can feel good about and feel and maybe feel healed if they come here … because people come and they make pledges and they make promises and they pray and they tie their prayer cloths and they burn their medicines,” Pratt said.

Other finalists note that just being recognized for their service should be healing for Native American vets.

“If you’re on the wrong side of history, you’re forgotten. I think it is very important in the healing process to really commemorate and honor those … that have sacrificed so much,” said James Dinh, another finalist.

-Cronkite News video by Shelby Lindsay

Dinh, whose father was a doctor in the South Vietnamese army, sees a connection between his cultural history and that of Natives who have served.

“I think everything I do has roots in my family histories or in the histories of Vietnamese Americans … we were displaced because of war,” he said, adding that Native Americans are also a displaced people.

“They never had a voice, and this memorial will allow this country to recognize their service,” Dinh said.

The finalists have until May 1 to “evolve and refine their design concepts to a level that fully explains the spatial, material and symbolic attributes of the design,” according to a National Museum of the American Indian news release.

The final concepts will be displayed at the museum from May 19 to June 3, and a winning design will be announced July 4. The actual memorial is scheduled to be completed by 2020.

Regardless of which design is selected, Pratt said the process already has made him “think about things a little deeper” than he ever had before.

“It’s very emotional to me to talk about veterans and guys that lost their lives and people who are going to lose their lives,” he said, “because I know some guys really suffer.”

Connect with us on Facebook.