Hopi students performed a social dance during a Hopi festival in Flagstaff last month. The economic future of the nation is uncertain as the Navajo Generating Station heads for closure in 2019. (Photo by Tanner Stechnij/Cronkite News)

SECOND MESA – Houses and corn fields dot the Hopi reservation, spread across three mesas in northeastern Arizona and circled by the much larger Navajo Nation. The seemingly barren Hopi land carries a rich, centuries old history and, now, an uncertain economic future.

New leadership – tribal members will choose a new chairman and vice chairman on Nov. 9 – will help determine a new reality for the Hopi nation as the Navajo Generating Station is slated for likely closure by December 2019. In recent years, royalties on land leases have made up to 85 per cent of the Hopi tribe’s general budget, according to tribal leaders and the Washington Times.

After the primaries in September cut down the field, two candidates for chair and two candidates for vice chairman are battling over the seats to lead the 22-member council.

Campaign issues include water quality, low employment, preserving the Hopi language and culture and finding jobs but candidates agree replacing income from the plant income is the most pressing matter facing the tribe.

Chairman Candidates

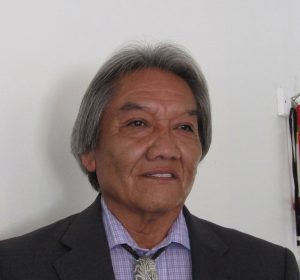

David Talayumptewa (Courtesy photo)

David Talayumptewa

The council member is a former deputy director for administration for the Bureau of Indian Education said he handled an annual budget of close to $1 billion.

Campaign platform: Talayumptewa plans to develop a Hopi immersion language program for two- to four-year-olds where students would speak and be spoken to only in Hopi. He’s also looking outside groups to pay $20 million for new water pipelines, which is equal to about a year’s budget for the Hopi Reservation.

Tim Nuvangyaoma (Photo by Tanner Stechnij/Cronkite News)

Tim Nuvangyaoma

A radio personality, Nuvangyaoma gave up his job at KUYI to run for office.

Campaign platform: Bolstering individual and village sovereignty and, to counter issues about drinking water quality, adding water vending stations and filters for sinks and other drinking spouts.

Vice Chairman Candidates

Clark Tenakhongva (Photo by Tanner Stechnij/Cronkite News)

Clark Tenakhongva

Tenakhongva is an Air Force veteran, formerly worked for the tribal police department and the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and has crafted kachinas.

Campaign platform: Instilling more opportunities for artists and other tribal members, such as more festivals in flagship locations like Sedona and Flagstaff.

Lamar Keevama (Courtesy photo)

Lamar Keevama

A council member for five years, Keevama also serves on the tribe’s water and energy commission and is former land commission chair. He also serves as a director of the Hopi Tribe Economic Development Corporation, an agency that owns properties across Arizona and looks to provide resources and jobs to Hopi artists and workers.

Campaign platform: Working on the tribe’s water rights, increasing services to tribal members and holding the federal government accountable for services and programs owed to the Hopi nation.

“This is such a thorn in our side,” said Tim Nuvangyaoma, a political newcomer who is vying to be tribal chair. “We knew about this a long time ago.”

His opponent, council member David Talayumptewa, also said the tribal council is hasn’t done enough to bolster its finance beyond coal leases.

“The tribe did not do anything until we were notified earlier this year that the Navajo Generating Station would close down,” Talayumptewa said. “Our tribe has been more of a reactionary government than really proactive.”

According to tribe documents, the Hopi nation typical general-fund budget ranges from $18 million to $22 million dollars. Last year, their general-fund budget was more than $21 million, with $16 million from royalties and other funds from the Navajo Generating Station, or about 75 percent of revenue, according to the tribe newspaper Hopi Tutuveni.

Hopi Tribal Council treasurer Robert Sumatzkuku did not respond to multiple requests for the 2017 budget.

Councilman Dale Sinquah, who is not running for office, said the council is working on plans to replace the income, such as leasing land to wind and solar companies and creating alternative energy partnerships. But those plans are preliminary and at least two years out, he said.

Coal plant headed for shutdown

The utilities and U.S.Bureau of Reclamation that own the Navajo Generating Station announced in February that the Navajo Generating Station, in operation since 1974, would be shut down by 2019 as coal lost economic ground to natural gas. The Hopi Tribal Council has depended on royalties from the coal plan for more than four decades, using funds to operate key areas like law enforcement, social services, veterans’ services and health care.

“I am concerned about our law enforcement, but we do have Bureau of Indian Affairs who has that trust responsibility to ensure that we are providing adequate law enforcement,” said Lamar Keevama, a candidate for vice chair. “Some of our other services may be affected, maybe the social services. I know that they’re now totally funded by the general fund.”

Representatives of the Salt River Project utilities company, which operates the generating station, had aired their concerns about its financial standing to the Navajo and Hopi tribe for more than a decade, according to SRP spokesperson Scott Harelson. He said each of the utility owners conducted their own research on the profitability of the station and came to the same conclusion.

“There are tremendous supplies of natural gas and that has brought the coal price down – and brought down the price to stay,” Harelson said. “So, the owners over time, SRP in particular, were somehow working against reality. We were spending a lot of time trying to figure out how can we keep the plant open.”

Peabody Energy, who owns the Kayenta Mine that provides coal to the generating station, is searching for a new buyer.

“The Department of the Interior is conducting a process to potentially identify new buyers for the plant,” Harelson said. “Peabody has retained a consultant to conduct that search.”

Harelson said the planned closure gives the Navajo Nation and the Hopi tribe new opportunities.

“The Navajo and Hopi tribe has the opportunity to create their own energy future here,” he said.

Difficulties lie ahead. Potential includes using renewable energy like solar. Chair candidate Talayumptewa said that the tribe has done the groundwork on creating a solar future. It’s now time to put it to use.

“There was a huge study done back in 2004 about the viability of solar energy,” Talayumptewa said. “We need to dust it off and take a look at it. It looks like something that really could be viable and most of the leg work on it has been done. It is a matter of investing into it and getting it to work.”

Keevama said that the council is already looking into solar projects and providing energy to Flagstaff as they try to become 100 percent green.

“Some might ask, why now when the tribe in the past hasn’t really considered solar projects, but the closure of the NGS is going to provide some capacity on that electrical transmission lines that run from NGS down south to other customers,” Keevama said.

Nuvangyaoma said diversifying income is the most important aspect to bolster the tribe’s energy revenues.

“I’ve been talking to a lot of our community members who have ideas and it’s time that we start listening to our community to maybe start executing some of these ideas, maybe strengthen them,” he said.

An election to define the future

Hopi members showed they wanted new representatives at the helm when voters tossed out chairman Herman Honanie and vice chairman Alfred Lomahquaha in the Sept. 14 primaries.

The candidates are facing an election before a weary electorate. Only ten percent of eligible voters turned out for the September primary and a low turnout is also expected for Thursday’s election, according to the Hopi newspaper.

The unemployment rate hovers at least 50 percent on a reservation where businesses like gas stations, grocery stores and restaurants are scarce.

Clark Tenakhongva says that most people living on Hopi make less than $35,000 a year. When the generating station closes he believes that food stamps and other programs will need to be bolstered.

“The people that are employed with the Hopi tribe are people that want to live here,” Tenakhongva said. “They don’t want to make the move to Flagstaff or Phoenix. It’s a big issue and I don’t know how the tribal council is approaching this…Because it’s going to impact all our people throughout the whole reservation.”

His opponent, Keevama, said an elderly tribal member said the reservation needs a hospital, not just a clinic, to better serve her husband, a veteran.

“They have to drive him to Prescott to the Veteran’s Affairs Hospital there,” Keevama said.

Textile weaver and teacher Justin Seakuku, who was selling his works in October at a Hopi festival in Flagstaff, said he didn’t vote in the Hopi nation’s primary and didn’t plan to vote in the November general election. (Photo by Tanner Stechnij/Cronkite News)

Textile weaver and teacher Justin Seakuku, who was selling his works in October at a Hopi festival in Flagstaff, said he didn’t vote in the primary and didn’t plan to vote in the November general election. He finds politics dishonest and in conflict with Hopi ideals.

“I’m a teacher and as a nation, I don’t know if we value education because of the funding and programs that get cut for our kids. Politicians like to use the platform that ‘children are our future.’ But no one has enticed me to vote yet.”

Talayumptewa, the council member who wants to be chair, said tribal leadership has been ineffective the past few years.

“People are going to have to trust once again how the tribe and the tribal council leadership operates,” he said. “When you take a look at the last four years and even beyond, not much has been accomplished. Probably one of the biggest thing is the coal issue.”

Nuvangyaoma said tribal government has not made the Hopi people a priority.

“Our jobs always seem to be going somewhere else instead of staying within the community,” he said. “Rightfully so, people are upset.”

Struggling as a way of life

Hardship is ahead as the tribe’s income sources remain in flux because of the impending closure, the candidates and other tribal members said.

But tribal members are familiar with uncertainty and struggle.

“The Hopi people believe they are the chosen people of the creator to live a life that is hard, to live a life that is humble, to live a life that takes a lot of work,” Seakuku said.

All of the candidates expressed working towards a more sustainable future for the Hopi. Tenakhongva said that starts with considering what the tribe needs ahead of everything else.

“Hopi needs to start standing up and saying that what belongs to Hopi must stay with Hopi,” Tenakhongva said referring to the natural resources on the reservation land.

Keevama said Hopi members will handle whatever is ahead. One of the Hopi villages is believed to be the longest continuously inhabited settlement in North America.

“Hopi are a strong, resilient people. We have been in this region for at least 1,000 years.” Keevama said. “Something like this isn’t really going to affect our ability to continue living.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave the wrong location for the Hopi reservation. It is in northeastern Arizona.