U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents patrol 1,100 square miles in the Nogales area. Data shows more than 3,000 unaccompanied minors were apprehended in the Tucson sector last year. (Photo by Maria Esquinca/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – They arrive at the federal courthouse each Friday, their hair neatly combed, dressed in the best clothes they own or can borrow.

At the U.S. border between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, about 3,300 unaccompanied children were apprehended in 2016. The sector encompasses 125,500 square miles and 268 miles of international border. (Photo by Maria Esquinca/Cronkite News)

The oldest is 17 years old. The youngest is 5. All of them are unaccompanied minors living in shelters, waiting to be reunited with a parent or guardian, granted asylum, or deported back to their home country.

More than 5,400 juvenile immigration deportation cases were heard in Arizona between 2005 and July 2017, according to data from the Executive Office of Immigration Review. The majority of these children and teens, more than 3,300, are from Guatemala. Another 1,000 are from Mexico. Honduras and El Salvador account for most of the rest.

An increasing issue

In 2014, an influx of 68,000 unaccompanied minors fleeing ongoing violence in Central American countries arrived in the United States, with many initially spending time in Arizona detention centers.

“For some part of the population, even the thought of crossing through Mexico to spending some time in detention in the United States has not been enough to deter people from trying because of the desperation they feel,” said Maureen Meyer, of The Washington Office on Latin America.

Honduras and El Salvador have had some of the highest murder rates in the world, according to 2014 data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Guatemala also was on the list, though some people chose to leave the country for purely economic reasons, said a spokesperson from the United Nations Human Rights Commission.

A report in May from Doctors without Borders, a nonprofit humanitarian aid organization, found more than 40 percent of Central American immigrants reported having been the victim of attacks or threats to themselves or their families.

“The root causes of why these children are fleeing — which is the violence, and that kids (girls and boys) are being targeted by gangs and narco traffickers — those have not changed but just coming here, making it across the border is more difficult,” said Megan McKenna of Kids In Need of Defense, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that provides free legal services for immigrant and refugee children.

Looking for asylum

On this particular day, in Courtroom 7 of the Phoenix Immigration Court, several unaccompanied minors with no legal way to stay in the U.S. will request voluntary departure, acknowledging the U.S. government has the right to deport them.

One of them is 10-year-old Pedro, who is from Guatemala. His father is in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody in Texas.

Pedro, who goes by Peter, is small for his age. Federal Immigration Judge John W. Richardson asks him if he can get up in the chair. He does, but his feet dangle above the floor. Richardson asks what he had for breakfast at the shelter. Peter doesn’t remember.

Peter’s lawyer requests a one month continuance to assess his case. His father has asked that he and his son be allowed to leave the country together. Richardson grants the request for continuance, and sets another court date for the following month.

On any given day, the judge, communicating through a translator, asks the same three questions to all of the children requesting voluntary departure.

“Are you from (country of origin)?”

“Are you willing to go back?”

“Do you have any fear of going back?”

If the answers are yes, yes, and no, the judge will grant their request for voluntary departure, and the child will have 120 days to leave the country.

More than 70 percent of juvenile immigrant cases in Arizona since 2005 have resulted in a removal order, or voluntary deportation, according to EOIR data. Children were allowed to stay in the U.S, through measures such as asylum, in approximately 5 percent of cases. The remaining 25 percent were pending, transferred, or closed for reasons such as lack of legal grounds to deport the child.

Children from noncontiguous countries are entitled to an immigration court hearing, like those that happen in Courtroom 7, before they can be sent home. Many children from Mexico and Canada are not, under the terms of the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008.

For those that get a hearing, whether or not they are allowed to stay often depends on whether or not they have a lawyer. In immigration court, unlike in criminal court, there are no public defenders. If defendants don’t have, or can’t afford, an attorney, they will go in front of the court without one, regardless of their age.

Despite the work of groups like The Florence Project that provide pro-bono services, 78 percent of juvenile immigrants in deportation cases in Arizona did not have a lawyer, EOIR data shows.

“Our youngest client was 2. We have 3-year-olds, 4-year-olds, 5-year-olds, and if they don’t have attorneys, there is just no way that they can represent themselves,” said McKenna. “It’s a pretty ludicrous system and it’s a bizarre thing to see to a little tiny kid going before an immigration judge sitting in a courtroom, and their feet don’t even come close to touching the ground.”

After the 2014 surge of unaccompanied children, the Obama administration created the Central American Minors program, or CAM. The program allowed children of legal U.S. residents to apply for refugee protection in the U.S. from within their home country. If the child qualified for refugee status, the program paid for them to travel to the U.S., and provided a pathway to legal citizenship.

Jessica Bolter of the Migration Policy Institute said that in order to qualify, applicants had to be unmarried, under 21, and able to prove they were fearful of remaining in their home country. They also had to prove their relationship to a legal U.S. resident with a DNA test.

The Trump administration ended part of the CAM initiative in August and will be winding down the CAM refugee program next year.

“It did fill a gap and kind of importantly, provided a messaging component on the part of the U.S. saying ‘There is a legal pathway for children to come join their parents so that they don’t necessarily have to undertake the dangerous journey up to the U.S. and crossing illegally,'” Bolter said.

She also said the number of children coming to the U.S. has started to rise again.

A rising tide

In Richardson’s courtroom on Sept. 15, nine other children and teens go before the judge. Three request voluntary departure, and will have until January 2018 to return home to Honduras and Guatemala. Four, including Peter, are working with lawyers to see if they have any legal grounds for asylum, and request a continuance. Three others have applied for visas, and are waiting to see if they’ll be allowed to stay.

More than 59,000 unaccompanied children arrived at the southwestern border in 2016, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, though some migrants are making the choice to seek asylum in Mexico instead, Meyer said.

“Between the situation not improving in the northern triangle countries to a greater awareness of that ability and also the unattractiveness of the U.S. to a lot of people right now, we are seeing Mexico become more and more a reception country,” she said.

The Washington D.C.-based Pew Research Center reported the number of unaccompanied minors being apprehended in Mexico increased 56 percent in 2015. The U.S. provided training, equipment and financial support to the Mexican government to help stem the flow of Central American migrants arriving at the southwestern border, according to a 2015 report from the Washington Office on Latin America.

The May 2017 Doctors without Borders report showed that nearly 68 percent of immigrants and refugees coming into Mexico reported having been the victim of violence along the journey to the U.S.

“Their families know these incredible dangers, but they make the trip anyway, because they often feel that they will come to great harm or even be murdered if they stay where they are in Central America,” said McKenna of KIND.

Many children simply turn themselves in when they reach the U.S. border, either to authorities at ports of entry, or to border guards, said the Migration Policy Institute’s Bolter. She said many of the children have contact information for their parent or guardian, and hope to be turned over to family eventually.

Finding their visas

Kelly Smith, a Yuma-based immigration attorney, said there are two main ways that unaccompanied children seeking refuge in the U.S. can be allowed to stay.

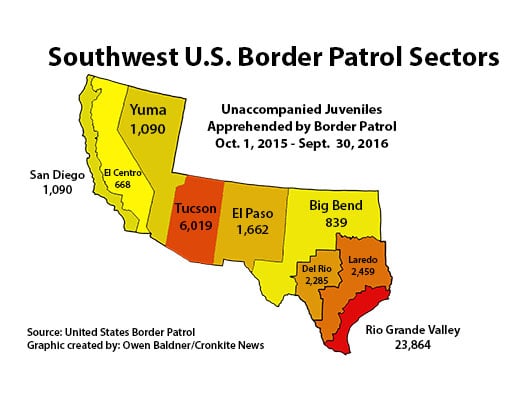

Southwest U.S. Border Patrol Sectors and the number of unaccompanied juveniles each has apprehended. (Owen Baldner/Cronkite News)

They may qualify for refugee asylum, or for a special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) or other type of visa. In order to qualify for an SIJ visa, it must be proven that the child can’t be reunited with a parent or guardian and that it’s not in their best interest to return home.

Once these qualifications are met, the child can apply for SIJ status through U.S. Custom and Immigration Services, and once that is granted, apply for a green card. There are also a limited number of asylum visas available.

“There’s asylum and refugee status which is also not super easy for many people to get. Often there are children in the system that do apply for that,” Smith said. “If they don’t have that available though, that’s why you are seeing voluntary departures.”

In order to qualify for asylum, children need to prove persecution in their home country, which means sharing stories of things that they have seen or experienced. McKenna said this can be traumatizing.

“Many of them have been through so much violence in their own lives and haven’t necessarily had someone to protect them and then they have to come to the U.S. and tell their stories of violence,” she said. “It can be hard for them too, and I don’t think they necessarily understand how important it is for them to tell the stories of everything that happened to them.”

Unaccompanied children are placed in shelters under the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Some don’t have anywhere else to go and may stay in a shelter until they turn 18 or are deported. But most of them will stay only until they are reunited with a parent or family member.

A sign at the U.S. border fence between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, warns people not to trespass. In 2016, most unaccompanied children coming into the U.S. were from Guatemala, El Salvador, or Mexico. (Photo by Maria Esquinca/Cronkite News)

Nearly 90 percent of unaccompanied minors in ORR care are released to a parent or close relative, according to a 2015 GAO report. Between January 2014 and April 2015, ORR released 50,000 unaccompanied minors to a sponsor to await an immigration hearing.

Of the 10 children in court on Sept. 15, three request reunification with a parent or guardian. After Peter is excused by the judge, he leaves the courtroom to meet with his lawyer and child advocate in the lobby. They give him high-fives, tell him he did a great job.

But the following month, Peter will be back in Courtroom 7. That’s when he’ll find out if he will be allowed to stay, be sent home with his father, or be sent home on his own.