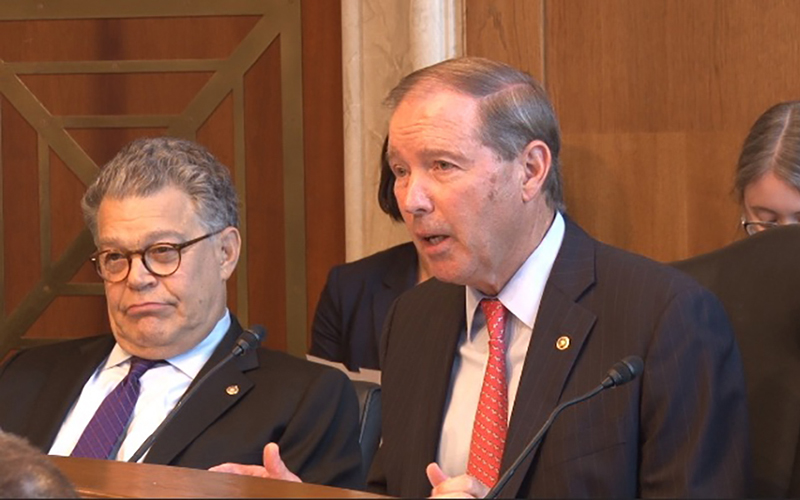

Heads of tribal-serving agencies that were criticized in GAO audits told a Senate committee that they are making progress, but Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico, right, said it seems “progress can only be made when Congress keeps the pressure on.” (Photo by Trevor Fay/Cronkite News)

A packed hearing room awaited the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs oversight hearing Wednesday into the ongoing shortcomings of three federal programs that have jurisdiction over Native American lands, schools and health care. (Photo by Adrienne St. Clair/Cronkite News)

Sen. John Hoeven, R-North Dakota, welcomed reports that agencies that handle tribal affairs are making progress. But the chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee also warned officials that “this will not be the last hearing on this issue.” (Photo by Trevor Fay/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Leaders of federal agencies serving Indian Country told a Senate panel Wednesday they have made some progress on dozens of problems cited in Government Accountability Office audits, but lawmakers said much more needs to be done.

The GAO put the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Bureau of Indian Education and Indian Health Services on its “high-risk” list of government areas in need of major improvement after nearly a decade in which the agencies addressed just two of a total of 41 recommendations on ongoing problems.

Officials from all three of the targeted agencies told the Senate Indian Affairs Committee they have started to address the issues in the GAO report, reducing bureaucratic roadblocks and implementing improved technology.

But the GAO’s Melissa Emrey-Arras testified that the number of problems identified at the agencies has grown from 41 when the high-risk list was published in February to nearly 50 after the completion of two additional reports on safety and construction in tribal schools.

Emrey-Arras said that while some of the GAO’s recommendations are intensive and require more collaboration, she said there are also easy fixes that are taking much longer than necessary.

See related story:

Ongoing problems land tribal oversight agencies on GAO ‘high-risk’ list

“It shouldn’t take four-and-a-half years to develop procedures to oversee school spending,” said Emrey-Arras, the GAO’s director for education, workforce and income security. But some of what she called the “low-hanging fruit recommendations” that should be done quickly are not expected to be done until 2019.

Tribal leaders have said they were not surprised by the GAO’s February report, a theme that was echoed by some lawmakers Wednesday.

“For years, the GAO has provided evidence of something many tribal communities have long reported, that bureaucratic barriers at agencies like the BIA, the BIE and IHS reduce the effectiveness of Indian programs across the federal government,” said Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico.

Udall said the high-risk designation proves that the agencies were not committed to resolving the GAO findings.

“It appears progress can only be made when Congress keeps the pressure on,” he said.

Sen. John Hoeven, R-North Dakota, also chided the agencies, particularly in regards to BIA’s handling of tribal energy resources where he said there has been “a lot of opportunity cost lost.” Hoeven, the committee chairman, told agency officials they need to look to long-term solutions but also for “some interim steps to help this along while you’re doing them.”

BIA’s progress with energy resources was a focus for a number of the senators. BIE and IHS both hold more open GAO recommendations, with 23 and 13 respectively, but both have reported more progress than BIA.

“BIE and IHS programs have benefitted from the additional scrutiny,” Udall said.

Michael Black, acting assistant BIA secretary, acknowledged in his testimony that “we still have a significant amount of work to do.”

Frank Rusco, director of natural resources at GAO, gave one reason for the problem: The BIA is not following exactly what the GAO wants them to do, and that more communication is needed, he testified.

“I wouldn’t characterize it exactly as an impasse, but we’re not exactly on the same page” when it comes to oversight at the agency level, he said.

BIA Director Tony Dearman was able to report Wednesday that his agency has simplified the teacher application process at BIE schools to address the problem of losing teachers from the reservations.

“That may be one of the best answers we’ve heard today,” Hoeven said. “That’s exactly what you should be doing is working with the state, leveraging your resources.”

But Sen. Al Franken, D-Minnesota, noted that problems other than those in the GAO report plague Indian Country.

Franken asked Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, the acting director of IHS, how the agency is addressing the opioid epidemic in tribal lands. He was not satisfied with Weahkee’s answer of “bringing the tribes to the table.”

“I just feel this is such a crisis, a devastation, and I just would like to see resources,” Franken said.

Despite the agencies’ shortcomings, Udall noted that tribal communities “can and do succeed.” But he emphasized the importance of federal agency support.

“Imagine how much more could be accomplished if their federal partners were offering them … support instead of getting in their way,” Udall said.

Hoeven asked Emrey-Arras for a timeline to follow up. She encouraged lawmakers to come back in six months, and Hoeven promised to do just that.

“Rest assured, this will not be the last hearing on this issue,” he said.