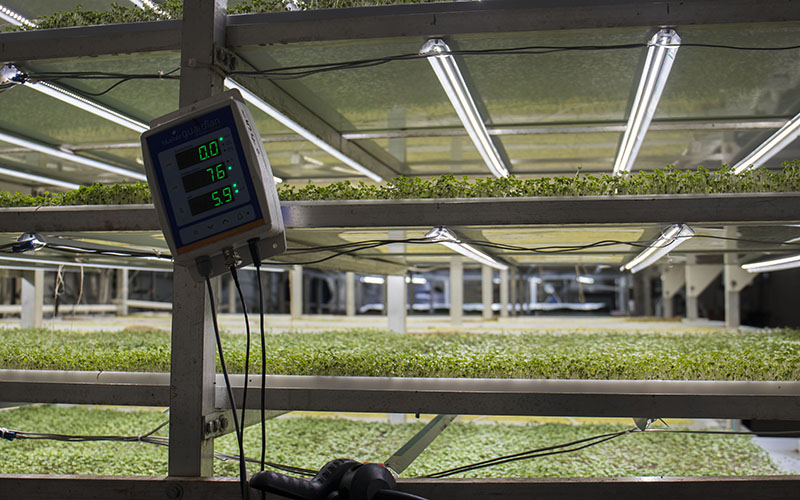

At Local Goods in California, Ron Mitchell’s monitoring system checks the plants’ water supplies for temperature, pH levels and electric conductivity. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

BERKELEY, Calif. – Tucked behind a Whole Foods in a corner warehouse unit, Ron and Faye Mitchell grow 8,000 pounds of food each month without using any soil, and they recycle the water their plants don’t use.

Hydroponic farming grows crops without soil. Instead, farmers add nutrients to the water the plants use. This method can produce a wide variety of plants, from leafy greens to dwarf fruit trees.

According to a study by the Arizona State University School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, hydroponic lettuce farming used about one-tenth of the water that conventional lettuce farming did in Yuma, Ariz. A similar study from the University of Nevada, Reno, found that growing strawberries hydroponically in a greenhouse environment also used significantly less water than conventional methods.

(Video by Jackie Wang/News21)

The Mitchells started production of Local Greens in February 2014. They primarily grow microgreens such as kale, kohlrabi and sprouted beans while using the same amount of water as two average households and the same amount of electricity as three in a month, they said.

“Who knows what you’re getting when you’re using soil?” Faye said. “Hydroponics is a fully contained system, so we know exactly what’s in our water, what we want in it and what we don’t want in it, and we can control that.”

Ron installed a water filtration system he customized. He removes fluoride, a common additive in municipal water, and chlorine, a common disinfection byproduct, before adding oxygen and other plant-specific nutrients.

At Local Greens, Ron and Faye Mitchell mostly cultivate microgreens, which grow to about 10 inches before they are cut and sold in the area. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

To make use of the warehouse’s tall ceilings, the Mitchells stack six trays of microgreen seeds on top of each other. At one end, an irrigation spout controls the amount and type of water sent through the trays.

“Some plants don’t need or want nutrients because they have it in their seed,” Ron said. He explained that pea shoots don’t need any additives, but sunflowers require copious amounts of nutrients to grow quickly.

Ron Mitchell, 67, said the stacked trays inside his hydroponic farming facility in California allow them to grow twice as much. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

The water the plants don’t use is captured at the other end of the tray and reused for the next watering, with the nutrients replenished as needed. The additional nutrients in the water are organic and naturally-occurring since they don’t have to spray pesticides or herbicides in their controlled warehouse environment, Faye said.

The number of greenhouse farms has more than doubled since 2007, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. Some hydroponics advocates see the practice as a solution to a global food and water crisis.

“I don’t think it could take over the farming industry entirely because of the types of plants and vegetables people want to eat,” Faye said. “But I definitely think it could make a dent in the farming industry and make its place and replace certain types of farms for a more efficient and, in some cases, less expensive system.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Troubled Water” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.