One of the many pictures of Jake Malkin with his sister, Tasha, on Facebook. (Courtesy Jake Malkin)

Dr. Jocelyn DeGroot researches grieving and social media. (Courtesy Dr. Jocelyn DeGroot)

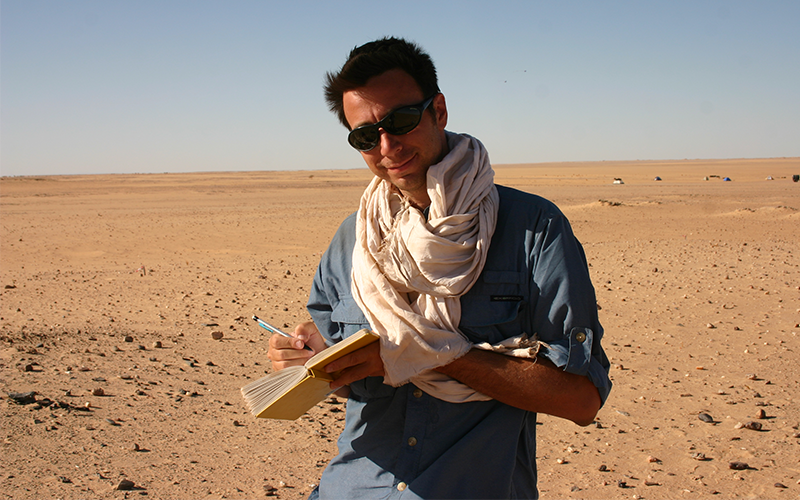

Dr. Christopher Stojanowski, an anthropologist, says the body is the “imprinted record” of someone’s life. (Courtesy ASU Now)

On this episode of In Focus, we look at what happens to social media accounts when you die. Producer Roddy Nikpour speaks to someone who had to deal with his sister’s death. He saw strange results when his family memorialized her Facebook profile, but modern research says they’re normal. Plus, an anthropologist sheds light on the importance of physical objects in remembering the dead.

The In Focus theme song is called “Wounds (Remix)” by Ketsa, used under Creative Commons.

Roddy Nikpour wrote the music used in this episode; you can listen to it on his Bandcamp page.

When Jake Malkin wants to remember his big sister Tasha, he plays her favorite Rachmaninoff piece or visits her Facebook profile. Her passion for music pervades the page, where friends post videos and images of Tasha, who died in 2013 at age 26.

“Her Facebook page is now more of a wall of remembering,” the 22-year-old Malkin said. “There weren’t many videos of my sister to begin with, so anytime I find any audio of her, especially of her singing or dancing, it’s a huge blessing.”

Tasha died on her drive to see a concert in Tucson when she was cut off and ended up running head-first into a pickup truck.

The In Focus theme song is called “Wounds (Remix)” by Ketsa, used under Creative Commons.

Before Malkin’s family memorialized her profile, Malkin said they first tried making a designated Facebook page for their sister’s memorial.

“But it started getting weird internet traffic from random people from very strange parts of the world,” Malkin said. “It just didn’t make sense.”

There is a growing field of research in digital memorialization. Dr. Jocelyn DeGroot of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville found that Malkin was witnessing something very common, and she coined a term for these cyber strangers: emotional rubberneckers. DeGroot observed that rubberneckers go to strangers’ pages for one of two reasons: to express sympathy or to get attention.

Meanwhile, Dr. Christopher Stojanowski, professor of anthropology at Arizona State University, says that physical artifacts can tell a story often truer than written words.

“I don’t know that email or Twitter or Facebook posts are going to be archived in the same way,” Stojanowski said, adding, “Facebook is very curated, right? Everyone has the best life imaginable.”

Despite this, Malkin will keep visiting his sister’s Facebook page every so often to reminisce and maybe discover some new photos or videos of her. But Malkin says he has to move on for the sake of his sister’s memory — and his own grief.

“Now I know that I need to build myself as a person and continue living my life and not be stuck in the past,” Malkin said. “That’s really important—not getting stuck in the past. […] You have to go through the pain of grieving, and however you do that, better that you just get through it and live your life for that person.”

Cronkite News consulted the Public Insight Network to find out how members of the public are preparing their cybergraves, if at all. Most of the respondents said they did not yet have plans to memorialize their profiles, but some have entrusted their login credentials with children and spouses.

Tim Haldane likens his deceased fiancée’s profile to a gravesite that’s “suspended in time” because he can visit it anytime from anywhere. Haldane appreciates the comfort he finds in the pictures of her and comments from friends.

Plus, Lori Fentem said that posting on the deceased’s page facilitates logistics of funeral planning and cultivates solidarity in grieving (backing DeGroot’s research). Others were more frustrated with the recurring memories.

On one hand, like Haldane, Fentem said that she is comforted by friends’ comments. On the other hand, Vince Lentini said social media “dehumanizes” the dead, alluding to DeGroot’s concept of emotional rubberneckers who seem to be seeking attention.