Two women walk through the mall at Arizona State University’s downtown campus on April 27, 2017. (Desiree Pharias/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — Usha Jagannathan applied for a full-time community college teaching position year after year for more than a decade. Within 13 years of graduating from her doctoral program in Technology and E-learning from Northcentral University, she worked as many as three jobs at a time.

Jagannathan worked in part-time university teaching in Michigan and Iowa, in addition to her full-time position as a senior IT consultant serving corporate clients nationwide through a subsidiary of The Washington Post Co.

With the multiple positions becoming increasingly difficult to juggle with her family life, she applied numerous times for full-time teaching positions, and despite meeting the stated requirements, she never received a position.

Often, Jagannathan said, the position would go to a man, and often they had less experience than she did.

Jagannathan pointed out that she could not say for certain if it the decisions were based on her gender, and that hiring could be based on other decisions made by the hiring committees, but she could not help but feel that her gender could be a main reason.

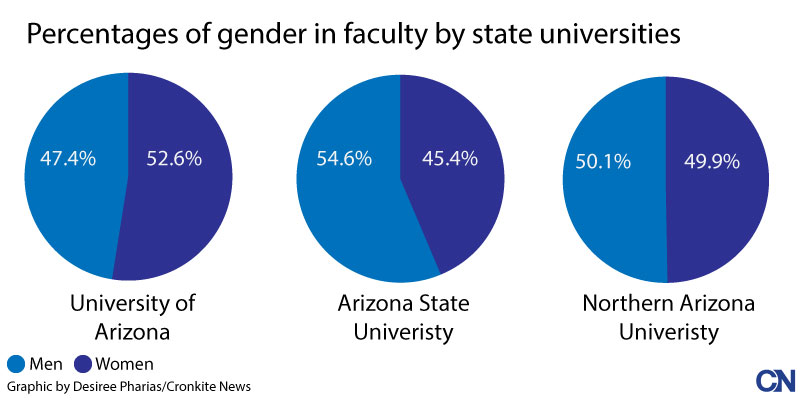

Across the nation, 46.5 percent of post-secondary educator positions are held by women.

Arizona percentages vary, but generally follow the national trend, with the University of Arizona at 43.2 percent women, Arizona State University at 45.4 percent, and Northern Arizona University at 49.9 percent in Fall 2016, according to the records of each university.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, nationally 96.8 percent of preschool and kindergarten teachers are women, 80.7 percent of women make up elementary and middle school teachers and 60.5 percent of women make up high school teachers according to the United States Department of Labor.

Lynda Ransdell, who is the Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs of the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University as well as an administrator and educator at the university level for multiple institutions over a number of years, emphasized the importance and expressed the need for training hiring committees and upper-division leadership roles in education to combat gender biases.

Ransdell also authored the paper, “Women as Leaders in Kinesiology and Beyond: Smashing Through the Glass Obstacles.” The paper includes a study exploring whether job applications submitted under the name “John” did better or worse than applications submitted under the name “Jennifer” for a lab manager position, decided by professors in chemistry, physics and biology.

The male applicant was rated higher in areas of competence, was more likely to be hired, and was offered more than the female applicant, despite having an identical resume in the study. The study showed that this bias was shown by both men and women.

In her position, Ransdell helps make sure that appropriate hiring processes are followed.

In areas that lack diversity, Ransdell said it is important to ensure that positions are advertised where they can reach a wider audience and receive a wider range of applicants.

“I think it’s important, I think you have to have higher diversity in leadership roles so that everybody that comes along after you has an opportunity to see that person in that leadership role,” Ransdell said.

Ransdell also noted that she believes diversity should come from race, nationalities and sexuality in addition to gender.

“It should be who our students see as leaders, because it is real life, it is real world,” she said.

Ransdell said in her time throughout academia, she has felt encouraged and rarely felt discriminated against. She also noted that she has been inspired by women in administrative positions throughout her career.

Regarding her noticing gender gaps at the university level Ransdell said, “I think it is a problem nationally, I don’t think it is just an institutional thing,” Ransdell said, “I think any institution can improve their ability to be equitable.”

Ransdell noted that she has seen this topic discussed at the universities she has worked at, but there is always room for improvement.

“I think the problem that I see is there is so much implicit bias, there’s so much that goes on behind the scenes, there are so many assumptions that are made that aren’t really discussed openly,” Ransdell said, “I think we need to do a better job discussing it openly and coming up with strategies.”

University organizations look to halt gender bias

Federal laws make it illegal for employers to discriminate against applicants or employees because of a person’s race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age or disability or genetic information.

But each Arizona university has also made efforts to bring more women into positions in education through university policies and campus organizations.

The Office of Equity & Inclusion at Arizona State University “promote(s) and assist(s) with equal opportunity and diversity initiatives,” not only in regards to gender, but also pertaining to “race, color, religion, national origin, citizenship, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, disability and qualified veteran status.”

ASU has extensive recruitment procedures put into place to ensure equal opportunity at every stage of the hiring process.

In addition, an association specific to faculty gender equality has been on campus since 1954. The ASU Faculty Women’s Association advocates for women faculty across the university and is a voice for gender equality in employment. Similarly, The University of Arizona has similar initiatives for faculty and development support within the university’s Center for Diversity and Inclusion. At Northern Arizona University The Commission on the Status of Women advocates for advances in equitable pay, promotion and workload for faculty and staff.

Diversity in STEM education

Each university’s gender percentages have increased. In 2007, NAU’s faculty were 44.9 percent female, ASU’s percentage was 41.8 percent and U of A’s was 40.9 percent, according to each university’s website.

Although the numbers are improving, there is still a gender disparity in higher education.

Ransdell also emphasized the importance of diversity in STEM education, and has been involved in organizations to emphasize the importance of STEM education. In 2013, just 39.4 percent of faculty members in STEM education were women, according to Association of American Universities Data Exchange.

Arizona State University’s Center for Gender Equity formed The National Stem Collaborative, which includes 12 higher education institutions and 15 non-profit partners across the country, in order to increase knowledge, research, resources and workforce development for women of color in STEM.

Finding a place with little bias

After overcoming her trials of finding a full-time faculty position, Usha Jagannathan has worked hard to promote diversity within STEM fields.

She is currently teaching Information Technology courses for ASU undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in the IT program, and she serves as a capstone co-chair and an applied project chair for iProjects, which places senior undergraduate and master’s program IT students at client sites for real-world applied projects.

“When I applied to ASU, it was very welcoming. … I am the one woman faculty in my department, and I never feel that I am out of place, ” said Jagannathan “I really credit ASU because I don’t see that bias, I see the gender equality.”

Jagannathan said she rarely saw these opportunities growing up in India.

“When I moved out of my rural town and came to the U.S., I felt like I also could be a part of a change,” Jagannathan said. She wants to see her students, and other women, given more opportunities.

Jagannathan assists in STEM programs for young people, and especially as a mother of two daughters, she said she wants to ensure children have opportunities to explore their fields of interest.

Jagannathan also judges science fairs across the nation and said she often she sees more boys than girls at the fairs.

To this, Jagannathan said, “given the right opportunity, any girl can shine.”

Female professors experience varying levels of bias

Not everyone has had such a positive experience with diversity at ASU.

Rachel Reinke, who is a professor of Women’s Studies at the school, said she has had a range of experiences regarding gender within her time as a student and as a professor.

Originally from Atlanta, Reinke earned her bachelor’s degree in English in Charleston, South Carolina.

“ASU is interesting because it is a very diverse population, especially compared to the area I grew up in, so I would expect a lot of good attitudes about gender diversity especially,” Reinke said.

Reinke, 29, started teaching courses as a graduate student, and although she noted ASU as a diverse institution, said she felt some level of discrimination.

“I had a lot of trouble being taken seriously when I was starting to teach my own classes. Because, I look younger than the average professor, and I am a woman, and I believe that has impacted people’s view of me,” Reinke said.

She said she often felt that her students would view her as inexperienced or under qualified because of her age and sex. This also occurred off campus. When telling people she had a Ph.D. and was teaching classes, they would be surprised.

“I’m not sure if that has so much to do with my age, but I definitely know that it has to do with my gender,” Reinke said.

In regards to faculty, Reinke said the experience is different. “I have a unique experience because there wasn’t much gender diversity in my department since the Women’s Studies department is almost all women.”

(Photo by Matthew via Creative Commons)

Reinke was inspired to go into Women’s Studies from inspirational mentors she had come into contact with in the same field, as well as the experience she received when earning her undergrad.

“I went to undergrad in the south, in Charleston, South Carolina. The English department there was majority white, majority male professors, and even if those weren’t my professors the materials they were teaching were definitely along those lines,” Reinke said.

Additionally, Reinke became increasingly inspired by Women’s Studies.

“When I thought about how much I had gained in my Women’s Studies classes and how important it was for me to have that critical aspect and be able to critique things from a perspective of gender, because that is such a formative experience for me both in school and out of school,” said Reinke. “I was lucky enough to be alive in a time where I could get my Ph.D. in Women’s Studies because it is a relatively new doctoral program.”

Throughout her education, Reinke explored Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning studies as well, and incorporates this into her classes, saying, “Race and class and sexuality all of those things are deeply connected to gender.”

“My experience is definitely shaped by being in the humanities,” said Reinke. “My experience is probably different from someone that is a professor in say, engineering, or something like that.”